Art of the Genre: The real ‘L’ word

I’m an old TSR module fan, and as such I’ve always been intrigued by how the concept of such media came into existence. For the most part they fall in series, kind of like writers follow Tolkien with the concept of connected books and characters in a trilogy. It makes perfect sense, especially if you’re trying to create an extended campaign with a gaming group that meets on a regular basis. Series modules facilitate that, and recently I had the opportunity to chat with one of the original designers of a TSR foundation adventure path, the L Series ‘Lendore Isles.’

I’m an old TSR module fan, and as such I’ve always been intrigued by how the concept of such media came into existence. For the most part they fall in series, kind of like writers follow Tolkien with the concept of connected books and characters in a trilogy. It makes perfect sense, especially if you’re trying to create an extended campaign with a gaming group that meets on a regular basis. Series modules facilitate that, and recently I had the opportunity to chat with one of the original designers of a TSR foundation adventure path, the L Series ‘Lendore Isles.’

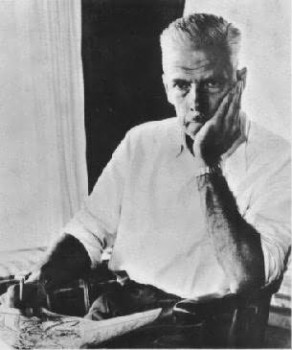

The author, Lenard ‘Len’ Lakofka is probably so ‘old school’ he’s beyond the term. His inclusion into the realm of RPGs predates the genre entirely, as he was a member of the International Federation of Wargaming. This institution came about in the sixties before the creation of Gygax’s Chainmail and was the original organizer of the first Lake Geneva Convention, i.e. GenCon in 1968.

At that first convention, people were playing Avalon Hill board games and Diplomacy during the Saturday only gathering, but that first year a chosen few were invited by Gygax to try Chainmail on the following Sunday after the convention was over. Lakofka was one of these founding fathers of the game.

From those humble beginnings, Chainmail would evolve into Dungeons & Dragons and Lakofka would continue to play the game with verve for the next forty years.

In one of my first posts here, I mentioned that I was hoping to figure out what it is, exactly, that I like about fantasy fiction; what it is I get from fantasy that I get nowhere else.

In one of my first posts here, I mentioned that I was hoping to figure out what it is, exactly, that I like about fantasy fiction; what it is I get from fantasy that I get nowhere else. Hallo again, Ye Faithful Paladins of the Black Gate!

Hallo again, Ye Faithful Paladins of the Black Gate! “For the love of God, not another one!”

“For the love of God, not another one!” Batman: Under the Red Hood (2010)

Batman: Under the Red Hood (2010) One of the characteristics of a great book is that you can go back to it at different times in your life and get different things out of it. But then sometimes the reverse happens: you read a book before you’re ready. If you’re lucky, though, the book hangs around in the back of your mind, and eventually you pick it up again and find out what you weren’t able to grasp the first time around.

One of the characteristics of a great book is that you can go back to it at different times in your life and get different things out of it. But then sometimes the reverse happens: you read a book before you’re ready. If you’re lucky, though, the book hangs around in the back of your mind, and eventually you pick it up again and find out what you weren’t able to grasp the first time around.

Swords From the West

Swords From the West