Birthday Review: Selina Rosen’s “Food Quart”

Selina Rosen was born on Groundhog’s Day in 1960. Her first story, “Closet Enlightenment” was published in Marion Zimmer Bradley’s Fantasy Magazine in the Summer 1989 issue. She founded Yard Dog Press in 1995. Through Yard Dog, she published the Bubba series of anthologies as well as novels written by a variety of beginning and mid-list authors. Rosen published her first novels in 1999 through Meisha Merlin. In 2011 Rosen received the Phoenix Award for Lifetime Achievement for the work she did at Yard Dog Press and for supporting and encouraging up and coming authors.

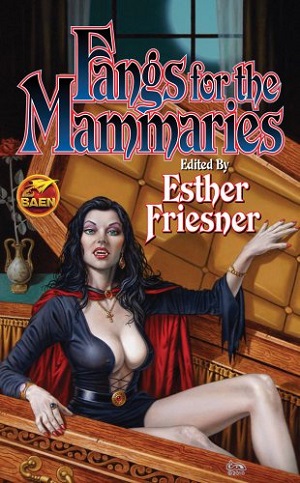

“Food Quart” was purchased by Esther Friesner for Fangs for the Mammaries, a 2010 anthology of humorous vampire stories set in suburbia. It has not been reprinted.

Mark has been working as a nighttime security guard at a suburban mall for three years when he’s called into his boss’s office over an incident the security cameras caught. A body had been found at the mall and while reviewing the evidence, Mark’s boss, Walt, and a local police officer began wondering why Mark didn’t appear in any of the security footage.

Having lived a long time, Rosen’s vampire is unconcerned being discovered. Rather than wait for his interrogators to come to their own conclusions about his nature, Mark admits it. Rosen’s story explores the response the three have to the revelation, from complete disbelief to acceptance to Mark’s plan to quickly leave the area and set up someone else, even as he comes to realize that he had been working at the mall longer than he had stayed in one place since becoming a vampire.

Rosen’s take on vampires is also quite mundane and she looks at what might be important to an immortal being and how they would view the world and protect their own existence. Mark is a long way from the vampires of Bram Stoker or F.W. Murnau or even Stephanie Meyer, offering instead the worldview of a working class version of Chelsea Quinn Yarbro’s Saint-Germain. A final encounter between Mark and Walt provides an unexpected ending for Mark as he prepares to leave for newer pastures.