Fantasia 2020, Part XXXVI: Anything For Jackson

Macbeth is one of the earliest true horror stories, in the sense of a story whose main aim is to play with the emotion of fear, and there’s a notable comic-relief scene with a gatekeeper right after the first gruesome murder. That scene became the subject of a famous essay by Thomas de Quincey arguing (roughly) that the horror’s made greater by contrast. So from the point where horror first began to emerge as a genre, storytellers have been conscious of the effect that comes from balancing horror with the everyday, and even with the comedic.

Macbeth is one of the earliest true horror stories, in the sense of a story whose main aim is to play with the emotion of fear, and there’s a notable comic-relief scene with a gatekeeper right after the first gruesome murder. That scene became the subject of a famous essay by Thomas de Quincey arguing (roughly) that the horror’s made greater by contrast. So from the point where horror first began to emerge as a genre, storytellers have been conscious of the effect that comes from balancing horror with the everyday, and even with the comedic.

Which was in my mind on the next-to-last-day of the 2020 Fantasia Festival, which began for me with two horror-comedies. The first was a Canadian film called Anything For Jackson, which looked like it would lean more to the horror aspect. More precisely, it looked a little like Rosemary’s Baby, only in this case perhaps intentionally funny and maybe actually scary.

Directed by Justin Dyck and written by Keith Cooper, it stars Julian Richings and Sheila McCarthy as Henry and Audrey Walsh, an elderly couple still mourning the death of their daughter and her young son Jackson. As the movie opens, they’ve abducted a young pregnant woman, Becker (Konstantina Mantelos), a patient of Henry, an obstetrician. Henry and Audrey have an evil ritual that will implant Jackson’s soul in Becker’s child’s body. Whether Becker likes it or not. Becker doesn’t want a child and doesn’t want an abortion, but she also doesn’t want this. Yet her attempts to escape are only one of the complications and challenges the Walshes encounter.

This movie works because Dyck and Cooper nail the tonal balance of the horror and the comedy. The first shot is a long take, about two and a half minutes, of a nice slightly dotty older couple going about their morning routine and then abducting a terrified young woman. The shift from gentle comedy to something deeply wrong is managed well, and the movie consistently gets that shift right not only from scene to scene but within a scene as well. The pacing and the scripting are exactly right in exactly the ways they have to be.

The film looks nice, too, colours muted and shadows thick. Winter snow echoes the emotional coldness underlying the story, and emphasises the Walshes’ home as both a place of confinement and a kind of sanctuary (for the Walshes). But over the course of the film horror imagery grows, as the Walshes experiment with the Satanic text they’ve found — possibly the oldest book in the world, we’re told — and more and more innocents stumble into the story.

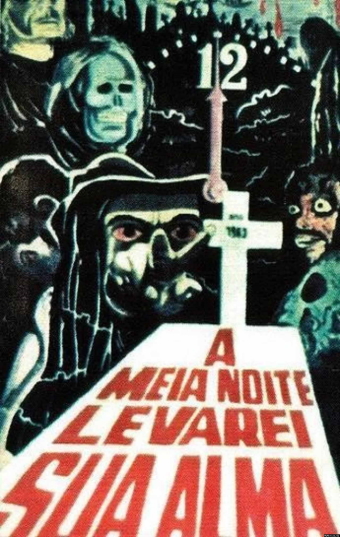

Brazilian director José Mojica Marins died earlier this year at the age of 83. He made low-budget films across a number of genres, with his horror work best known. His character Coffin Joe (Zé do Caixão), introduced in the 1963 film At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul (A Meia Noite eu Levarei sua Alma) is a kind of national ghoul of Brazil. Fantasia decided to honour Marins by making three of his films available on-demand through the festival, and scheduling a talk about Marins with his friend Dennison Ramalho on the last day of the festival;

Brazilian director José Mojica Marins died earlier this year at the age of 83. He made low-budget films across a number of genres, with his horror work best known. His character Coffin Joe (Zé do Caixão), introduced in the 1963 film At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul (A Meia Noite eu Levarei sua Alma) is a kind of national ghoul of Brazil. Fantasia decided to honour Marins by making three of his films available on-demand through the festival, and scheduling a talk about Marins with his friend Dennison Ramalho on the last day of the festival;

Film noir’s usually thought of as an urban genre. Its standard setting is the mean streets down which a man must go who is not himself mean. But a city’s not necessary; the Criterion Channel recently hosted a collection of Western Noir, films like Rancho Notorious and The Walking Hills. The ingredients for noir — violence, criminality, a morally bleak world — can be brought together anywhere.

Film noir’s usually thought of as an urban genre. Its standard setting is the mean streets down which a man must go who is not himself mean. But a city’s not necessary; the Criterion Channel recently hosted a collection of Western Noir, films like Rancho Notorious and The Walking Hills. The ingredients for noir — violence, criminality, a morally bleak world — can be brought together anywhere.

The Western’s an American genre in origin, but Europeans from Sergio Leone to Charlier and Moebius have done interesting work in the form. Usually, though, European Westerns follow American heroes. That is, the European creators are still telling American stories. Savage State (L’État Sauvage), a Western from French writer/director David Perrault, does something different, following a French family trying to get out of the American South during the Civil War. It’s a nice idea. Unfortunately, the execution’s lacking.

The Western’s an American genre in origin, but Europeans from Sergio Leone to Charlier and Moebius have done interesting work in the form. Usually, though, European Westerns follow American heroes. That is, the European creators are still telling American stories. Savage State (L’État Sauvage), a Western from French writer/director David Perrault, does something different, following a French family trying to get out of the American South during the Civil War. It’s a nice idea. Unfortunately, the execution’s lacking. Every story’s got a genre, even if the story’s the sole example of its genre, so by extension a lot of stories use genre conventions and trust that the audience will accept them even if they’re unlikely or unbelievable. Often the audience does, especially when the conventions are so common they don’t register as conventions. But a story usually works better the more it can justify its conventions. Especially when the justification, and the convention, work with the story’s theme.

Every story’s got a genre, even if the story’s the sole example of its genre, so by extension a lot of stories use genre conventions and trust that the audience will accept them even if they’re unlikely or unbelievable. Often the audience does, especially when the conventions are so common they don’t register as conventions. But a story usually works better the more it can justify its conventions. Especially when the justification, and the convention, work with the story’s theme.

One of the crucial differences between the way a storyteller approaches the tale they’re telling and the way the audience experiences that tale is that the storyteller typically knows the ending in advance. If they don’t start with the ending and work to that, they’ve usually still worked out multiple drafts of the story, if only in their head. The audience, on the other hand, at least on their first experience of a story doesn’t get to the end until they’ve gone through the whole of the work leading there. Even if they’ve heard something of the ending, or guess at it, the body of the work is necessarily the main part of the experience. If you just get the ending, you haven’t really gotten the whole story.

One of the crucial differences between the way a storyteller approaches the tale they’re telling and the way the audience experiences that tale is that the storyteller typically knows the ending in advance. If they don’t start with the ending and work to that, they’ve usually still worked out multiple drafts of the story, if only in their head. The audience, on the other hand, at least on their first experience of a story doesn’t get to the end until they’ve gone through the whole of the work leading there. Even if they’ve heard something of the ending, or guess at it, the body of the work is necessarily the main part of the experience. If you just get the ending, you haven’t really gotten the whole story. There is a certain tone I find in some works of science fiction, almost all from Europe, a ‘literary’ approach that uses science-fictional imagery with self-conscious irony in a way that at least approaches allegory and often satire. In prose I associate this approach with Lem and indeed Kafka; in film, with Tarkovsky’s science-fiction (adapting Lem and the Strugatskys) and Alphaville and On The Silver Globe. The focus in these works is less on world-building than on symbolism, and often on a narrative structure that layers stories within stories and plays with chronology. At their best, these tales emphasise the purely fantastic essence at the heart of science fiction: a type of wonder that uses a modern vocabulary.

There is a certain tone I find in some works of science fiction, almost all from Europe, a ‘literary’ approach that uses science-fictional imagery with self-conscious irony in a way that at least approaches allegory and often satire. In prose I associate this approach with Lem and indeed Kafka; in film, with Tarkovsky’s science-fiction (adapting Lem and the Strugatskys) and Alphaville and On The Silver Globe. The focus in these works is less on world-building than on symbolism, and often on a narrative structure that layers stories within stories and plays with chronology. At their best, these tales emphasise the purely fantastic essence at the heart of science fiction: a type of wonder that uses a modern vocabulary.