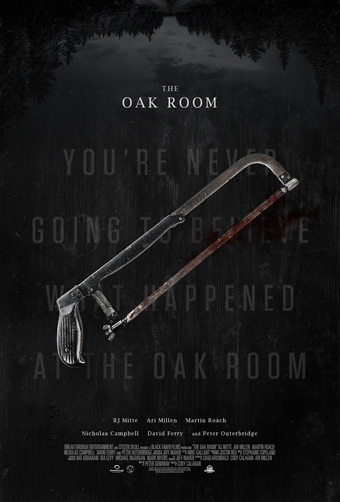

Fantasia 2020, Part XXXIV: The Oak Room

Film noir’s usually thought of as an urban genre. Its standard setting is the mean streets down which a man must go who is not himself mean. But a city’s not necessary; the Criterion Channel recently hosted a collection of Western Noir, films like Rancho Notorious and The Walking Hills. The ingredients for noir — violence, criminality, a morally bleak world — can be brought together anywhere.

Film noir’s usually thought of as an urban genre. Its standard setting is the mean streets down which a man must go who is not himself mean. But a city’s not necessary; the Criterion Channel recently hosted a collection of Western Noir, films like Rancho Notorious and The Walking Hills. The ingredients for noir — violence, criminality, a morally bleak world — can be brought together anywhere.

Thus The Oak Room. Directed by Cody Calahan, with a script by Peter Genoway based on his own play, it’s a rural Canadian noir that plays with narrative and genre. You can see the preoccupations of CanLit — fathers and sons, hopelessness and a lack of escape, the harshness of the land. But you also see noir: an atmosphere of violence, a sense that everybody’s compromised, shadows and night. There’s no femme fatale here, no women at all, in fact; but there is a concern with truth, as characters tell each other stories and teach other how to bullshit. What’s true and what’s false and why the characters are telling each other the things they do become increasingly important, questions even of life and death.

There’s perhaps less a plot to The Oak Room than a structure, a framework filled with stories and discussions of storytelling. It begins one night in the middle of a snowstorm with a man walking into a bar off a highway in western Ontario. The customer, Steve (RJ Mitte) has a history with the bartender, Paul (Peter Outerbridge). Steve’s come to pick up his dead father’s things from Paul, who’s been holding them. Paul isn’t shy about telling Steve he’d be a disappointment to his old man, but Steve starts telling him a story, about a man who walks into a bar in rural Ontario one night in the middle of a snowstorm.

Why he tells the story, and what happens in it, become a large part of what The Oak Room is about. The conflict between Paul and Steve plays out on a number of levels, and goes to unexpected places. In particular there’s a story that gets told around the middle of the film about Steve’s father which gives a theological tone to events by illustrating a specific kind of damnation. It echoes the theme of mortality, but it also gives the movie a weight, a sense of the meaning behind events and why these stories matter.

On the flip side, that story’s image of damnation could be described as what happens when you have no story to tell yourself about your life and future. This is a movie about storytelling, about the motives for telling stories and about the ways stories have a power over their audience. It’s more cynical than most stories with that theme, though. Stories here delay and obfuscate and set up their audiences as marks. You could call it a movie about the danger of storytelling, but also a movie about how you need stories, and how you can use them.

Maybe more specifically than being about stories, it’s about storytelling. Paul gets frustrated with Steve’s way of telling a story, beginning with the ending, and gives him tips: you have to “goose the truth,” he says. The more the film goes on the more you become aware of Paul as a storyteller, a master bullshitter, a veteran bartender. Outerbridge’s acting is sensational, he portrays Paul as a bitter man (so providing another angle on the central story’s bitterness) but verbally quick. He’s clever and strong-willed in a way that feels like a familiar small-town character. Outerbridge takes sharp, confrontational dialogue and wrings out of it every bit of threat and anger there is; his delivery’s immensely entertaining to watch. Mitte matches that with a Steve who’s bitter in a different key, weak (or seems so), clever (but possibly not as much so as he thinks), younger and less assured than Paul and in danger of being overwhelmed by him.

Maybe more specifically than being about stories, it’s about storytelling. Paul gets frustrated with Steve’s way of telling a story, beginning with the ending, and gives him tips: you have to “goose the truth,” he says. The more the film goes on the more you become aware of Paul as a storyteller, a master bullshitter, a veteran bartender. Outerbridge’s acting is sensational, he portrays Paul as a bitter man (so providing another angle on the central story’s bitterness) but verbally quick. He’s clever and strong-willed in a way that feels like a familiar small-town character. Outerbridge takes sharp, confrontational dialogue and wrings out of it every bit of threat and anger there is; his delivery’s immensely entertaining to watch. Mitte matches that with a Steve who’s bitter in a different key, weak (or seems so), clever (but possibly not as much so as he thinks), younger and less assured than Paul and in danger of being overwhelmed by him.

Their performance strikes a balance between the theatrical and the real — between the need for dramatic conflict, and the slightly-too-loud aggression you get between a man with very little patience and a guy he has to deal with but doesn’t like much and who himself has no taste for direct confrontation. That balance speaks to the overall theme of stories, maybe, but it also points up how the movie doesn’t feel like a play. It never feels stage-bound, even though almost everything in this movie takes place in a couple of bars, with flashbacks illustrating stories. There’s a cinematic feel to the way it presents its actors, getting in close to their gestures and points of view.

There’s something in the movie a little like Tarantino; it’s a structurally clever crime story revolving around men who swear creatively. There’s a similar focus on masculinity, and on male spaces — bars, and gas stations, and a father and son doing a bit of bloody work in a barn. There’s more humanity here, though, more of a sense of life. More of a sense of place, and what life is like in that place. The rural setting shapes the characters, defines them, gives their confrontations and backstories a specific flavour. CanLit, Canadian literature, is easily stereotyped; it’s routinely mocked as stories about people in small towns struggling with meaningless lives and troubled relationships with fathers. Which are fine themes, but too often come off as whingeing from people in a basically comfortable country who don’t have real problems in their lives. The Oak Room takes some of those premises and fuses them with crime fiction to get a real kick, a sense of implicit violence.

There’s something in the movie a little like Tarantino; it’s a structurally clever crime story revolving around men who swear creatively. There’s a similar focus on masculinity, and on male spaces — bars, and gas stations, and a father and son doing a bit of bloody work in a barn. There’s more humanity here, though, more of a sense of life. More of a sense of place, and what life is like in that place. The rural setting shapes the characters, defines them, gives their confrontations and backstories a specific flavour. CanLit, Canadian literature, is easily stereotyped; it’s routinely mocked as stories about people in small towns struggling with meaningless lives and troubled relationships with fathers. Which are fine themes, but too often come off as whingeing from people in a basically comfortable country who don’t have real problems in their lives. The Oak Room takes some of those premises and fuses them with crime fiction to get a real kick, a sense of implicit violence.

This is the kind of movie that demands a second viewing, which I suspect would make it work even better. At one viewing, the end’s a little non-specific — when all’s said and done you have a general sense of what’s happened and why, but I think there’s more detail to be had from a second watch. It’d be worth doing, one way or another; it’d be worth watching the twists again. There’s a lot to learn in this movie about storytelling. And what’s most ironic is that Calahan and Genoway do here the opposite of what conventional wisdom says storytellers are supposed to do, especially in film: this is a story all about characters telling, not showing. This is a film that shows why it’s called storytelling and not storyshowing, and it’s wonderful to watch.

This is the kind of movie that demands a second viewing, which I suspect would make it work even better. At one viewing, the end’s a little non-specific — when all’s said and done you have a general sense of what’s happened and why, but I think there’s more detail to be had from a second watch. It’d be worth doing, one way or another; it’d be worth watching the twists again. There’s a lot to learn in this movie about storytelling. And what’s most ironic is that Calahan and Genoway do here the opposite of what conventional wisdom says storytellers are supposed to do, especially in film: this is a story all about characters telling, not showing. This is a film that shows why it’s called storytelling and not storyshowing, and it’s wonderful to watch.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.