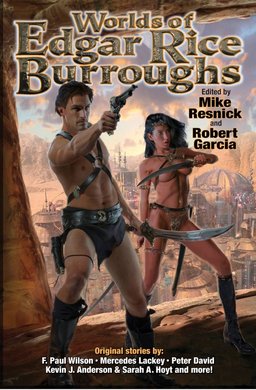

New Treasures: Worlds of Edgar Rice Burroughs

I had the pleasure of talking to Bob Garcia a few weeks ago, at a party at Doug Ellis‘s house near Chicago. Bob is a great guy — always jovial and superbly well-informed, and always ready to entertain with fascinating, behind-the-scenes tales of the publishing biz. His American Fantasy was one of the finest fantasy magazines of the 80s, and ever since he’s been well-positioned at the heart of the industry.

I had the pleasure of talking to Bob Garcia a few weeks ago, at a party at Doug Ellis‘s house near Chicago. Bob is a great guy — always jovial and superbly well-informed, and always ready to entertain with fascinating, behind-the-scenes tales of the publishing biz. His American Fantasy was one of the finest fantasy magazines of the 80s, and ever since he’s been well-positioned at the heart of the industry.

I took the opportunity to ask him about his new anthology, Worlds of Edgar Rice Burroughs, co-edited with Mike Resnick, just published by Baen on October 1st. It’s such a great idea — all new stories set in the many worlds of ERB, by many of today’s hottest writers — that it’s a wonder no one has thought of it before.

Bob was happy to give me the details. The book contains ten new tales set in the legendary worlds of Edgar Rice Burroughs — plus one reprint, Resnick’s novella, “The Forgotten Sea of Mars,” which originally appeared in the fanzine ERB-dom way back in 1966. This is the only Mars/Barsoom story in the book, as Disney now controls the rights to Burroughs’s Mars properties.

The book suffers not at all for that, however. When Bob and Mike started approaching writers, soliciting submissions, they were overwhelmed by the enthusiastic response. The final Table of Contents includes a new Tarzan tale by Kristine Kathryn Rusch, a Carson Napier of Venus homage by Richard A. Lupoff, a Moon Maid contribution from Peter David, a Mucker story from Max Allen Collins and Matthew Clemens, a Pellucidar story by Mercedes Lackey, a crossover tale by Joe R. Lansdale (“Tarzan and the Land Time Forgot”), plus stories by F. Paul Wilson, Todd McCaffrey, Kevin J. Anderson and Sarah A. Hoyt, and Ralph Roberts.

Here’s a few sentences from the introduction by Resnick and Garcia that give you an idea of the breadth of Burroughs’s accomplishments and just how vast a playground he left for their contributors to play in.