Take Me Down to the “Parasite Planet” (Where the Grass Is Really Disgusting)

Last week, our esteemed editor John O’Neill posted a wonderful reminiscence of one of the key science-fiction anthologies of the 1970s: Isaac Asimov’s Before the Golden Age. This hefty volume (sometimes divided over three paperbacks) is an intriguing mixture of autobiography, literary analysis, and miles o’ great pre-Campbellian magazine science fiction. Before the Golden Age is a classic piece of early pulp archaeology.

Last week, our esteemed editor John O’Neill posted a wonderful reminiscence of one of the key science-fiction anthologies of the 1970s: Isaac Asimov’s Before the Golden Age. This hefty volume (sometimes divided over three paperbacks) is an intriguing mixture of autobiography, literary analysis, and miles o’ great pre-Campbellian magazine science fiction. Before the Golden Age is a classic piece of early pulp archaeology.

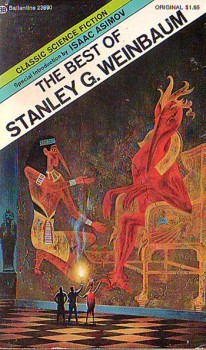

O’Neill’s post specifically made me recall “Parasite Planet” by Stanley G. Weinbaum. I did not read this story for the first time in Before the Golden Age, but in The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum. This book, which contains an introduction from Isaac Asimov and an afterword by Robert Bloch, is the first of Del Rey’s many “The Best of . . .” collections, a series I credit with getting me interested in many of the classic science-fiction authors of the mid-twentieth century. I still own my yellowed copies of The Best of John W. Campbell, The Best of Jack Williamson, The Best of Leigh Brackett, The Best of C. L. Moore, The Best of L. Sprague De Camp, and The Worst of Jefferson Airplane. (Wait, one of these things is not like the other. . . .)

I first read “Parasite Planet” in The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum, but the Del Rey edition was not my initial encounter with Mr. Weinbaum. That came through another of the great anthologies of the ‘70s (wow, I am really hitting “great anthologies” in a big way in this post), The Science Fiction Hall of Fame. Weinbaum’s 1934 classic, “A Martian Odyssey,” was the first story in the collection, and also its oldest. The vote of the Science Fiction Writers of America that determined the contents of the collection picked the story as the second best SF short piece ever published, with only Asimov’s “Nightfall” besting it. “A Martian Odyssey” floored me when I first read it at age eighteen, and so I had to find out more about this Weinbaum guy who seemed to have vanished, since he was one of the few authors in The Science Fiction Hall of Fame whom I did not recognize from later achievements.

There turned out to be, unfortunately, a tragic reason for this. Weinbaum burst onto the SF scene with “A Martian Odyssey,” which was his first sale. He was immediately the most popular author in the field; everybody loved his work. Eighteen months later, in December 1935, Weinbaum was dead from lung cancer at age thirty-three.

In a way, Weinbaum was science fiction’s equivalent of Robert E. Howard: a hugely talented author who died too young. But Weinbaum’s run was even shorter than Howard’s—a mere year and a half, with twelve stories published during that time. Posthumous work followed, but considering the immense talent that Weinbaum shows in his fiction—starting with his first story!—it is frustrating how little of this gold strike ever got to the surface for readers to mine.

Although Weinbaum was an author “before the Golden Age,” meaning that he was writing before John W. Campbell took over Astounding Stories in 1937 and molded the field to his liking, Weinbaum seems like a Golden Age author. His themes and his open writing style were far ahead of what all other authors were doing at the time, and everyone recognized it at once. Weinbaum was a “Campbell author before Campbell.” Asimov, one of Weinbaum’s major promoters, had this to say about what would have happened if Weinbaum had lived a full life and continued to write:

“A Martian Odyssey” appeared a year before [Campbell’s story] “Twilight,” so Weinbaum is clearly one author who owed nothing to Campbell. Had Weinbaum continued producing there would have been no Campbell revolution. All that Campbell could have done would have been to reinforce what would undoubtedly have come to be called the “Weinbaum revolution.”

And in Weinbaum’s giant shadow, all the Campbell authors would have found themselves less remarkable niches. Weinbaum . . . would surely be in the first place in the list of all-time favorite science-fiction writers.

I’ll even go this far: If Weinbaum had managed to live as long as, say Robert A. Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, A. E. Van Vogt, Arthur C. Clarke, and (dare to dream) Jack Williamson, he would have been the first recipient of the Grand Master Award when it began in 1975. The award must go to a living author, and so it was Heinlein who received the first honor. But Heinlein certainly wouldn’t have begrudged a living Stanley G. Weinbaum getting it first.

“A Martian Odyssey” and its sequel, “The Valley of Dreams,” are classics that I’ve read many times. Weinbaum’s alien creations are amazing, having logical biology and reasons to exist aside from providing a bad guy. This is why Weinbaum’s sudden appearance on the scene (and in the most minor of the science-fiction mags at the time, the ailing Wonder Stories) blew readers’ minds . . . nobody had treated aliens with such detail and, dare I say, ethnological respect. It wiped away the Homo sapien-centric views of previous science fiction. Weinbaum’s debut was, as Asimov later termed it, the second “Supernova” of magazine science-fiction, a publication event that changed the direction of the genre and turned everyone else into an imitator. (The other two are E. E. Smith’s The Skylark of Space in 1928 and Robert A. Heinlein’s “Life Line” in 1938.)

Yet I think Weinbaum reached his height with 1935’s “Parasite Planet,” published in the February issue of Astounding Stories during the tenure of F. Orlin Tremaine as editor. This was the story that hooked the young Isaac Asimov, who called it “the most perfect example of an alien ecology ever constructed.” In Before the Golden Age, he remarked that it “hit me with the force of a pile driver and turned me instantly into a Weinbaum idolater.”

The plot of “Parasite Planet” is a straight-forward survival adventure with nothing startling about it if laid out in outline. “Ham” Hammond, a trader on Venus collecting xixtchil pods to sell for medicinal properties, loses his protective shack to a mudspout, and has to head for the nearest American settlement. Along the way he meets another explorer, Patricia “Pat” Burlingame, who also loses her dwelling, and the two of them go on a survival quest while bickering with each other. Patricia thinks of Ham as nothing more than poacher . . . but of course we know where this relationship will end up.

The plot of “Parasite Planet” is a straight-forward survival adventure with nothing startling about it if laid out in outline. “Ham” Hammond, a trader on Venus collecting xixtchil pods to sell for medicinal properties, loses his protective shack to a mudspout, and has to head for the nearest American settlement. Along the way he meets another explorer, Patricia “Pat” Burlingame, who also loses her dwelling, and the two of them go on a survival quest while bickering with each other. Patricia thinks of Ham as nothing more than poacher . . . but of course we know where this relationship will end up.

Typical pulp material. But . . . Venus! Oh wow Venus! Weinbaum’s extrapolation from contemporary scientific knowledge creates one of the most fascinating and deadly settings in the history of speculative fiction. Ham and Pat move through a nightmare of wild nature where even the slightest mistake results horrid death in the most hostile environment imaginable.

This Venus has a permanent day and night side, with human habitation only possible along “the twilight zone” (hee-hee), a five hundred-mile wide region around the middle of the planet. But this region is a mass of vegetation, heat, storms, mudspouts, and a rapid death for any human who doesn’t take the most strenuous precautions.

Not only is this Venus a perfect setting for adventure, it makes complete ecological sense. The obstacles that Weinbaum hurls at his two heroes don’t exist just because life has to be tough for Pat and Ham. Like his famous intelligent alien creatures, the flora and fauna of Weinbaum’s Venus exist on their own first—the logic of their biology when contrasted with the outsider is what makes them so dangerous.

Weinbaum expends great amounts of prose explore the strange setting so that it lives for the reader, none of it wasted:

All life on Venus is more or less parasitic. Even the plants that draw their nourishment directly from the soil and air have also the ability to absorb and digest—and, often enough, to trap—animal food. So fierce is the competition on that humid strip of land between the fire and the ice that one who has never seen it must fail to even imagine it.

The animal kingdom wars incessantly on itself and the plant word; the vegetable kingdom retaliates, and frequently outdoes the other in the production of monstrous predatory horrors that one would even hesitate to call plant life.

Weinbaum also adds emotion to the setting, with Ham repeatedly thinking things such as “A disgusting sight! A disgusting planet!” It is revolting. Creepers, strangling Jack Ketch trees, hordes of moving fungi . . . the story is a catalog of pestilent and deadly life. The doughpout, “a mass of white, doughlike protoplasm, ranging in size from a single cell to perhaps twenty tons of mushy filth . . . in effect, a disembodied, crawling, hungry cancer” is one of the most nauseous creatures I’ve ever read about in science-fiction literature.

On top of the deadly animal and plant life and the mudspouts and storms, the tiniest exposure of skin or the smallest breath of Venusian air results in a grotesque end: spores instantly sprout in nostrils, mouth, lungs, ears, and eyes in “furry and nauseauting masses.” Good times, come here and buy a summer home!

To boil it down, “Parasite Planet” is thrilling and intelligent science fiction from first word to last. Even if our knowledge of Venus has changed to make the science of “Parasite Planet” obsolete, the story has hardly aged at all. If submitted to The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction today, it would get purchased in a heartbeat, and go on to win the Hugo and the Nebula for Best Short Story.

Weinbaum wrote two sequels to “Parasite Planet” which followed the further adventures of Ham and Pat: “The Lotus Eaters” (Astounding Stories, April 1935) where they travel to the mysterious night-side of Venus and find fascinating communal plant life that they name “Oscar”; and “Planet of Doubt” (Astounding Stories, October 1935) which takes them to Uranus. Both stories contain more of Weinbaum’s signature aliens of utter amazement and are excellent—although I’ve honestly never read a Weinbaum story I didn’t think was first-rate. However, “Parasite Planet” remains for me the ultimate Weinbaum work, and an example of world-building in totality that goes above and beyond what most writers in speculative fiction even dare to dream possible.

By the way, this is my personal favorite title I’ve put on any of my Black Gate posts. One day, I will complete the transformation of “Paradise City” into the song “Parasite Planet” and sing it at some convention until I am viciously beat.

Ryan,

I think we must have read Weinbaum in exactly the same order — starting with The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, and then The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum. Ah, the 70s certainly were the heyday for anthologies, for me anyway (the other one I remember really enjoying at the time was The Early Asimov).

Weinbaum, along with Edmond Hamilton, Clifford Simak, and of course Charles Tanner, was responsible for my early love of the pulps. It wasn’t hard to figure out that the fiction I most enjoyed originated in those early magazines.

Have you read Weinbaum’s novel, THE BLACK FLAME? I admit I haven’t, but I’ve recently become more curious about it.

John

Oh, and if we’re picking favorite Ryan Harvey blog titles, my vote goes to March, 2009’s “Who Watches the Watchmen? I Watches!” 🙂

John

Ashamed to admit I have not read The Black Flame yet, John, but it’s definitely on my list.

The Science Fiction Hall of Fame was responsible for introducing me to a lot of the big names that I still read. Aside from “A Martian Odyssey,” I was also astonished with “Nightfall”, “Surface Tension,” “It’s a Good Life,” and “Who Goes There?”

Glad you liked that “Watches” title gag. I seriously thought the God of Grammar would drop a split infinitive on my head for that one!

[…] with enough wonders to fill the galaxy—it becomes difficult to stop. Pondering the marvels of Stanley G. Weinbaum’s 1935 classic “Parasite Planet” urged me to shift through my pile of Del Rey “Best of . . .” paperbacks, which are crammed with […]

[…] time we’ve covered Weinbaum’s career. The distinguished Ryan Harvey wrote a terrific retrospective three years ago, where he said, in […]