Adventure On Film: The Color of Magic

Once upon a very suspect time, a human being by the name of Terry Pratchett conjured up a space-traveling sea turtle by the name of A’tuin, and proceeded to make a sizable fortune from the disc-shaped world he emplaced upon her. In Pratchett’s Discworld novels, magic of the most unpredictable kind is the norm, and so it should come as no surprise that, eventually, somebody had to commit his unique brand of literary lunacy to celluloid.

Once upon a very suspect time, a human being by the name of Terry Pratchett conjured up a space-traveling sea turtle by the name of A’tuin, and proceeded to make a sizable fortune from the disc-shaped world he emplaced upon her. In Pratchett’s Discworld novels, magic of the most unpredictable kind is the norm, and so it should come as no surprise that, eventually, somebody had to commit his unique brand of literary lunacy to celluloid.

And so they did. The Color of Magic appeared in 2008, destined for British TV and comprised of two longish episodes.

Now, having admittedly come rather late to the Discworld table –– I read a short called “Troll Bridge” years ago, but didn’t realize it was part of a larger cycle –– my somewhat limited exposure was nonetheless sufficient to convince me that Pratchett’s novels were congenitally unfilmable.

Despite that dire opinion, I am happy to report that Sean Astin is delightfully droll as Twoflower, the Discworld’s first tourist, and David Jason is about as Rincewind as anyone could possibly be. As a murderous and ambitious wizard, Tim Curry simpers and smirks as only Tim Curry can, (although he doesn’t appear to be having nearly as much fun as he did as “Arthur King” in Spamalot). On an ankle-biting budget, the cinematography is generally first rate, as are most, though not quite all, of the props. Death –– a nuisance, and constantly in pursuit of Rincewind –– is lovingly voiced by Christopher Lee, but disappoints the eye. Bearing a cheap-looking sickle, Death appears to have just wandered in from a middling haul of Trick-or-Treats.

Physically, then, in real-world terms, The Color of Magic is of course filmable –– as is just about everything these days, including massive sand worms and infinitesimal specks of pollen. I even recall seeing, on Nova, an attempt to demonstrate string theory’s ten dimensions on the two-dimensional plane of a television screen –– an abject failure, yes, but I blame myself. My limited powers of imagination and whatnot. Me and my four-dimensional mindset.

So let me amend my question: can The Color of Magic be adapted to film successfully?

‘His eyes were icy verdigris, but warm also, and piercing — in a kind way. He was dressed smartly in a long coat of an almost military cut and dark pants with gold piping.’ So writes the narrator of the 2012 story, “The Portobello Cetacean” as she first lays eyes on her host, Sgt. Roman Janus, late of Mount Airy, the man known as the ‘spirit-breaker’.

‘His eyes were icy verdigris, but warm also, and piercing — in a kind way. He was dressed smartly in a long coat of an almost military cut and dark pants with gold piping.’ So writes the narrator of the 2012 story, “The Portobello Cetacean” as she first lays eyes on her host, Sgt. Roman Janus, late of Mount Airy, the man known as the ‘spirit-breaker’. Arthur Machen first published a version of “The Great God Pan” in 1890, in a magazine called The Whirlwind; then revised and extended the tale for its republication as a book in 1894, when it was accompanied by a thematically-similar story called “The Inner Light.” It’s a fascinating work, creating a horrific mood mostly through suggestion and indirection. Nowadays, one looks at it and notes very Victorian attitudes toward women. At the time of its original publication, the story’s implied sexuality caused real scandal.

Arthur Machen first published a version of “The Great God Pan” in 1890, in a magazine called The Whirlwind; then revised and extended the tale for its republication as a book in 1894, when it was accompanied by a thematically-similar story called “The Inner Light.” It’s a fascinating work, creating a horrific mood mostly through suggestion and indirection. Nowadays, one looks at it and notes very Victorian attitudes toward women. At the time of its original publication, the story’s implied sexuality caused real scandal. Titus Crow first appeared in Lumley’s 1971 story, “The Caller of the Black”. Crow’s credentials as a psychic sleuth and occult investigator are impressively vetted in the story, as he defeats both mortal and immortal enemies through the cunning application of the standard Lovecraftian eldritch lore, a shower faucet and a window pole. From the outset, it is clear that Crow inhabits the same deadly universe as

Titus Crow first appeared in Lumley’s 1971 story, “The Caller of the Black”. Crow’s credentials as a psychic sleuth and occult investigator are impressively vetted in the story, as he defeats both mortal and immortal enemies through the cunning application of the standard Lovecraftian eldritch lore, a shower faucet and a window pole. From the outset, it is clear that Crow inhabits the same deadly universe as

I get more and more e-mails about the sources I use to write about ancient Arabia, and questions about those sources come up more and more frequently every time I turn up on a convention panel. As a result, I took a long post live on my blog today about one of my favorite books, a historical memoir from the 11th century. When I talk about any of my sources in person I can only tell you how good I think it is. One of the benefits about putting my thoughts in writing is that I can provide examples from the text to prove my point.

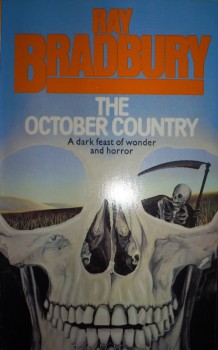

I get more and more e-mails about the sources I use to write about ancient Arabia, and questions about those sources come up more and more frequently every time I turn up on a convention panel. As a result, I took a long post live on my blog today about one of my favorite books, a historical memoir from the 11th century. When I talk about any of my sources in person I can only tell you how good I think it is. One of the benefits about putting my thoughts in writing is that I can provide examples from the text to prove my point. I came to Ray Bradbury at what is likely a later age than most. I never had to read Fahrenheit 451 in school; if I read one of his short stories as a student I have no recollection. Several years ago, in a desire to start filling in some gaps I had in classic genre fiction, I gave Fahrenheit 451 a try. It was a powerful read and made a profound impact on me. It prompted me to seek out more Bradbury—and I’ve been hooked ever since.

I came to Ray Bradbury at what is likely a later age than most. I never had to read Fahrenheit 451 in school; if I read one of his short stories as a student I have no recollection. Several years ago, in a desire to start filling in some gaps I had in classic genre fiction, I gave Fahrenheit 451 a try. It was a powerful read and made a profound impact on me. It prompted me to seek out more Bradbury—and I’ve been hooked ever since.