The End of the World and Everyone Knows It

I’ve always had a hankering for apocalyptic fiction. It probably goes back to the original Planet of the Apes being one of the first big-screen movies I ever experienced, though I was too young to appreciate or remember more than a flash or two — “Daddy, why is is that monkey riding a horse?”. I was probably asleep by the time Heston knelt in the sand in front of the Statue of Liberty. Does that still count as a spoiler? Nevertheless, it seems to have left an impression.

I’ve always had a hankering for apocalyptic fiction. It probably goes back to the original Planet of the Apes being one of the first big-screen movies I ever experienced, though I was too young to appreciate or remember more than a flash or two — “Daddy, why is is that monkey riding a horse?”. I was probably asleep by the time Heston knelt in the sand in front of the Statue of Liberty. Does that still count as a spoiler? Nevertheless, it seems to have left an impression.

Recently, there’s been a boomlet of what I call full-stop apocalyptic movies. What I’m talking about is the sort of movie where everyone, and I do mean everyone, dies at the end thanks to some earth-ending cataclysmic event. No escaping to another world on a spaceship ala When Worlds Collide (or getting picked up by a Vogon construction fleet). Nope, the curtain comes down on everything and everyone in one dreadful, final coda.

You have to be in the right sort of mood to enjoy this kind of thing. I find a largish whiskey helps. While it sounds bleak, as an author or dramatist, the idea isn’t without merit. We’re all going to be face-to-face with death at some point. In this sort of story, all your characters are going to be meeting death at about the same time. The interest comes in seeing how each recognizes, struggles against, and eventually experiences their final moments, singly or together.

Why so many of these films have cropped up in the last decade or so is a question no one’s really asked and only a mass psychologist could answer. I’ve a pet theory or two, but no interest in wasting time on political/economic dogma. Instead, let’s get down with the sickness.

On The Beach (1959)

The grandfather of the genre was a nuclear scare drama based on Nevile Shute’s impressively bleak novel, where the southern hemisphere is slowly succumbing to the radiation seeping south created by the “Short War” involving radiological-warfare cobalt bombs among the northern nations in the previous year. Stanley Kramer disposes of the science, simplifies the politics, and ratchets up the melodrama from Shute’s restrained and perceptive pathos, but the emotional core of the novel is intact. The film accurately and harrowingly depicts human civilization “running down” in the last few months before the end, where all the characters are given the grim choice between a messy, gut-emptying death by radiation sickness or government issued suicide pills (“They’re on the free list,” a pharmacist reassures a young father).

The four main characters each have their own way of dealing with what’s coming. Peter Holmes (a pre-Psycho Anthony Perkins), the young Royal Australian Navy Lieutenant, is balancing duty at sea with duty to his wife and baby daughter. He’s the character who accepts what’s coming head-on, faces it, and spends all his time working to make things easier for everyone else. Dwight Townsend (Gregory Peck), the sole American, is the skipper of a nuclear submarine tasked with investigating theories and flickers of life in the radioactive northern hemisphere. He’s utterly by-the-book and unimaginative, and deals with the war and death of his family in the States as just an unusually long duty separation; he’ll rejoin them in the fall after Australia “goes out.” In the novel, he even goes so far as to purchase presents to bring home, to make up for missed birthdays and the extended time away from his wife. John Osbourne (is that really Fred Astaire?) is a scientist investigating the radiation’s effects (even though the information he’s learning is ultimately useless since everyone will be dead in a few months, he’s still fascinated to learn new facts), and in his spare time he’s taken up a lifelong dream, auto racing, thanks to the purchase of a Ferrari for pocket change from the widow of a racer who was caught by the war in England. Finally, there’s Moira (Ava Gardner), Peter’s sister-in-law, who has nothing to keep her occupied while waiting to die, and has found solace in brandy and transitory affairs. She develops a tragic love for Dwight, and finally acts as a chaste replacement for Dwight’s dead wife, keeping him company and doing his mending and plucking the stuffing out of the utterly correct naval officer whenever she has an opportunity. Their unique love affair is the heart of the story, set to the Banjo Patterson bush ballad “Waltzing Matilda,” an Australian classic that’s easily the most rollicking ditty about death you’ll ever hear.

Ultimately, the Australians go to their shared end in an orderly fashion, picking up their suicide pills dressed in their Sunday best.

It’s a riveting movie, one I can’t resist watching whenever it drifts across my channel-flipping transom. It was remade about a decade ago as a two-night miniseries, but a good deal is lost in the expansion (though they did have the courtesy to at least cast some Australians to play Australians).

I highly recommend the novel, however. It’s much the superior of both filmed versions.

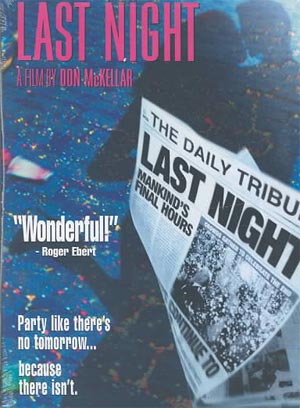

Last Night (1998)

This strong Canadian movie doesn’t even bother explaining what’s about to happen when the world ends at midnight, though it gives a few hints that might mean something to an astrophysicist. The cause, however, is incidental, the fact of its approach drives the story, covering the six hours of the last night on and of Earth.

This strong Canadian movie doesn’t even bother explaining what’s about to happen when the world ends at midnight, though it gives a few hints that might mean something to an astrophysicist. The cause, however, is incidental, the fact of its approach drives the story, covering the six hours of the last night on and of Earth.

Last Night started out as a film project about Y2K, but the writer/director Don McKellar decided to do something that would still resonate after the millennial turn. Vestiges of the original idea still echo — it’s a bit odd that the word is ending at exactly midnight, Toronto time.

While no doubt south of the border we’re all losing our collective shit like Butterfly McQueen in a Mumbai maternity ward, up north they’re looking at this as one last, proud opportunity to not get too torqued up about things. Despite the government having collapsed some months ago, everyone in Canada seems to be getting on with what’s left of their lives and meeting their end in whatever manner seems fitting.

The main character, Patrick (played by our auteur McKellar, pulling an Orson Welles better than the man himself ever managed, IMO), has decided to meet his end alone in his apartment, for reasons that the film slowly reveals. His mother is still being passive-aggressive about the decision in a last family dinner. His best friend is hurrying to finish his list of living out every sexual fantasy he’s ever had, including doing it with a grammar school French teacher he had a crush on (ably played by a still-impressive Geneviève Bujold). Sandra Oh, the reigning queen of this sort of quirky indie flick, is “Sandra” (perhaps even playing herself, she does get semi-recognized), a woman trying to get home to a dinner with her husband who is stranded when her car is disabled by a mob when she stops to loot a bottle of wine. Patrick’s sister has reunited with a boyfriend and is meeting the end with him, and a few other interesting minor characters whose paths will cross in one way or another make the film fly by.

Watch this one with someone, because you’ll need to talk about it afterward. It’s that good.

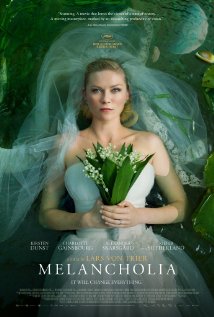

Melancholia (2011)

This one is hard for me to recommend, though I really liked it, because I know it’ll put at least eight out of ten viewers off and a couple of you will be tempted to punch me in the nose for wasting your time and money. C’est la cinema.

This one is hard for me to recommend, though I really liked it, because I know it’ll put at least eight out of ten viewers off and a couple of you will be tempted to punch me in the nose for wasting your time and money. C’est la cinema.

Danish bad-boy (and depressive) Lars von Trier got the idea for Melancholia from a session with his therapist, who pointed out that depressives often handle calamity very well: they’re used to things being terrible, so they have more coping skills to get on with the job.

It’s the story of two sisters, Justine (the always amazing Kirsten Dunst) and Claire (Charlotte Gainsborough — and don’t ask me why one sister has an English accent and the other doesn’t), told in two halves named after the sisters. The first half is Justine’s wedding, held at the golf resort owned by Claire’s husband, John (Kiefer Sutherland). It’s an expensive wedding, as John reminds us several times. After seeing a colorful star in the sky Justine doesn’t recognize, she slowly and methodically goes to pieces over the course of the evening, ruining her career (in a spectacular slagging of her boss), John and Claire’s patience (inevitably), and her wedding (finally, when the poor frustrated groom Alexander Skarsgård departs into the night, never to be seen again). Curiously, this echo’s Von Trier’s own self-destruction at a press conference around the time of the premiere, where he decided to use his microphone to defend the Nazis.

Justine is either bipolar or precognitive, or possibly both. The second half of the film takes place some time after the wedding. The star Justine spotted is a blue planet, Melancholia, which is scheduled to make a spectacularly close pass to Earth before wandering off. Some fear a collision (but not the confident-on-the-surface John). Justine has come to stay a while with her sister, who seems used to handling Justine’s condition. Poor Claire has a lot to juggle: her son, who is worried about the approach of Melancholia, her depressive sister, and John, who wants everyone happy about the one-in-a-billion chance at seeing such cosmic awe.

Things go from spectacular to worse, and, conforming to Von Trier’s psychoanalyst’s observation, Justine has to step up and see it through, for the sake of her terrified nephew if no one else.

Kirsten Dunt’s naked figure, bathed in the painterly light of the approaching Melancholia is highly recommended. As for the rest of the movie, if this sort of thing is your cup of tea, you’ve probably already seen it.

Seeking a Friend for the End of the World (2012)

I went to see this one the first weekend it was out, and good thing I did because it died at the box office. The trailer promised a dark comedy starring Steve Carell, typecast once again into middle-aged disappointment. The movie delivered more melodrama than dark comedy, when it wasn’t trying to be an end-of-the-world road trip romcom. While various scenes in the film work very well and held my interest, it never quiet gelled as a whole.

I went to see this one the first weekend it was out, and good thing I did because it died at the box office. The trailer promised a dark comedy starring Steve Carell, typecast once again into middle-aged disappointment. The movie delivered more melodrama than dark comedy, when it wasn’t trying to be an end-of-the-world road trip romcom. While various scenes in the film work very well and held my interest, it never quiet gelled as a whole.

Anyway, Matilda is a huge asteroid on a collision course with Earth (perhaps the name of the asteroid is a tribute to On The Beach, I’ll have to wait for the director’s commentary to find out). It opens on a hopeless note. As Dodge (Carell) and his wife (Carell’s real-life spouse Nancy) listen to the news on the radio that the Armageddon/Deep Impact-style rescue mission to stop the comet failed in a spectacular mishap, Dodge’s wife gets out of the idling car and literally runs off as fast as her legs will carry her.

What follows is Dodge dealing with what remains of his career and empty home life. He tries to commit suicide by drinking Windex, but wakes sick as a dog and tied to one bearing only a piece of paper reading “Sorry.” He names to pooch Sorry and adopts him. He grows closer to one of his longtime neighbors, free-spirited Penny (Keira Knightly), who flits through this movie like Tinkerbell in a Bertolt Brecht play and they strike up an increasingly intimate friendship. When he finds her despairing over her inability to get home to her family in England for the end, he offers to get her a plane and pilot, and the two humans plus Sorry set out from the increasingly chaotic city into the country.

What follows are several darkly funny or poignant set pieces in the road trip. The highlight for most viewers will be a meal at a TGI Friday’s-style eatery where the management has left but the workers keep sort of a wild cargo-cult of upbeat dining going (having worked food service, I found it a bit beyond belief, but the scene’s genius). The picture doesn’t decide what it is until Martin Sheen shows up. His great performance and interaction with Carell and Knightley finally gives the picture an emotional tone it is able to maintain until (literally) the end.

Maybe I was expecting too much. I’ll give it another shot on home video and I might find I like it better.

Maybe I was expecting too much. I’ll give it another shot on home video and I might find I like it better.

The mini-genre’s not quite played out yet. Edgar Wright has teamed up with Simon Pegg and Nick Frost (the trio from the Britcom Spaced, and movies Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz) for The World’s End, supposedly the concluding film of either the “Blood and Ice Cream Trilogy” or “Three Flavor Cornetto Trilogy,” depending on who you ask. Supposedly it will begin filming in October for a 2014 release. It’s about an epic pub crawl and the possible end of the world.

We’ll see, but I find I have high hopes for this particular wipeout of mankind.

I was probably asleep by the time Heston knelt in the sand in front of the Statue of Liberty. Does that still count as a spoiler? Nevertheless, it seems to have left an impression.

Well, of course! He was kneeling in sand.

[…] The-End-of-the-World-as-Everyone-Knows-It […]