The Cold Edge of Forever, I: Equations

I want to write about Star Trek. Specifically, about the episode “The City on the Edge of Forever.” But I’m not going to do that right now. I’ll get there, but I’m going to start off by writing about a well-known prose sf story that to me parallels “City” in some interesting ways. Then, in my next post, I’ll go on to write about the Trek episode and make a fuller comparison (edit to add: time having passed, you can find the post here). First up, though: “The Cold Equations.”

I want to write about Star Trek. Specifically, about the episode “The City on the Edge of Forever.” But I’m not going to do that right now. I’ll get there, but I’m going to start off by writing about a well-known prose sf story that to me parallels “City” in some interesting ways. Then, in my next post, I’ll go on to write about the Trek episode and make a fuller comparison (edit to add: time having passed, you can find the post here). First up, though: “The Cold Equations.”

“The Cold Equations” was written in 1954 by Tom Godwin for editor John W. Campbell and published in Astounding. Some, including writers Kurt Busiek and Lawrence Watt-Evans, have stated that the story was largely borrowed from an EC Comics short story by Al Feldstein with art by Wally Wood, “A Weighty Decision,” itself perhaps copied from an E.C. Tubb story (“Precedent”). At any rate, Godwin’s tale is well-known, having been adapted for the screen and frequently anthologised; I read it in The Road to Science Fiction 3: From Heinlein to Here.

A man, Barton, piloting a small spaceship carrying medicine to an isolated colony, discovers an eighteen-year-old stowaway, Marilyn, who wanted to see her brother on the colony world. But Marilyn, from Earth, doesn’t understand the way things work out on the frontier of space: the ship had exactly as much fuel as it needed to get to the planet — before Marilyn’s unexpected weight was added. With Marilyn, it won’t be able to land safely. For the people on the colony world to live, she has to be ejected from the ship. Barton frantically tries to find some way out, some way to keep her alive, but cannot; and so, willingly, she goes into the airlock, and dies out in the void of space. Physics and mass and momentum cannot be argued with, the story tells us; the cold equations must balance.

Of the many useful terms suggested by John Clute in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, perhaps the most useful is the idea of ‘thinning.’ Clute sees certain archetypal patterns frequently recurring in fantastic fiction and thinning’s a part of that. It is the lessening that afflicts threatened fantasylands, a type of diminishment. It’s the fading of magic, the passing of the great old order. Sometimes, eventually, the greatness of the past is restored, though perhaps in a different form.

Of the many useful terms suggested by John Clute in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, perhaps the most useful is the idea of ‘thinning.’ Clute sees certain archetypal patterns frequently recurring in fantastic fiction and thinning’s a part of that. It is the lessening that afflicts threatened fantasylands, a type of diminishment. It’s the fading of magic, the passing of the great old order. Sometimes, eventually, the greatness of the past is restored, though perhaps in a different form. Somehow, when I was growing up, I missed Witch World. Some of the books in the series were always around, as I remember it, in my local libraries and bookstores, but I don’t think I ever read one — if only because I always try to read a series in order, and finding Witch World itself was not always easy. Somewhere along the line, though, I picked up a used copy, and set it aside to be read later. As it happens, there’s been a certain amount of talk about Andre Norton lately,

Somehow, when I was growing up, I missed Witch World. Some of the books in the series were always around, as I remember it, in my local libraries and bookstores, but I don’t think I ever read one — if only because I always try to read a series in order, and finding Witch World itself was not always easy. Somewhere along the line, though, I picked up a used copy, and set it aside to be read later. As it happens, there’s been a certain amount of talk about Andre Norton lately,  I’ve always had a fascination with Frtiz Lang’s Metropolis that I’ve never been able to explain. Obviously, it’s a visually powerful film and a tremendous influence on

I’ve always had a fascination with Frtiz Lang’s Metropolis that I’ve never been able to explain. Obviously, it’s a visually powerful film and a tremendous influence on  It’s not uncommon for writers of fictions called ‘literary’ to use science-fictional or fantastic elements in their work. And it’s not uncommon for sf readers to suggest that they’re using those elements wrongly, with a lack of understanding of the material they’re working with — usually, depending on the specific case, either because the writer didn’t understand the history of the way the element in question has been treated in prior (genre) works, or simply because they haven’t thought the logic of what they’re doing through in a rigorous way. Personally, I find this is rarely a problem in the fantastic ‘literary’ works that I read. And, intriguingly, when it is a problem, it’s not necessarily a significant problem.

It’s not uncommon for writers of fictions called ‘literary’ to use science-fictional or fantastic elements in their work. And it’s not uncommon for sf readers to suggest that they’re using those elements wrongly, with a lack of understanding of the material they’re working with — usually, depending on the specific case, either because the writer didn’t understand the history of the way the element in question has been treated in prior (genre) works, or simply because they haven’t thought the logic of what they’re doing through in a rigorous way. Personally, I find this is rarely a problem in the fantastic ‘literary’ works that I read. And, intriguingly, when it is a problem, it’s not necessarily a significant problem. You never know when you’ll find something fantastical to write about.

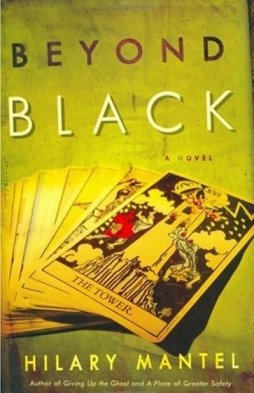

You never know when you’ll find something fantastical to write about. Hilary Mantel’s two novels of Tudor-era statesman Thomas Cromwell, 2009’s Wolf Hall and 2012’s Bring Up the Bodies, have both won the Man Booker prize; a third, The Mirror and the Light, will complete the trilogy, but has not yet been scheduled for publication. I want to write here not about those books, but about 2005’s Beyond Black, the last book Mantel published before embarking on the Cromwell trilogy. Her ninth novel, it was shortlisted for the Commonwealth Writers Prize and the Orange Prize. It’s a novel of the fantastic, in the broadest sense, and can be approached as fantasy, as horror, even as noir; but may be best understood simply as a thing in itself.

Hilary Mantel’s two novels of Tudor-era statesman Thomas Cromwell, 2009’s Wolf Hall and 2012’s Bring Up the Bodies, have both won the Man Booker prize; a third, The Mirror and the Light, will complete the trilogy, but has not yet been scheduled for publication. I want to write here not about those books, but about 2005’s Beyond Black, the last book Mantel published before embarking on the Cromwell trilogy. Her ninth novel, it was shortlisted for the Commonwealth Writers Prize and the Orange Prize. It’s a novel of the fantastic, in the broadest sense, and can be approached as fantasy, as horror, even as noir; but may be best understood simply as a thing in itself. A few years ago, a cat came to live with me under unexpected circumstances. (This is getting around to a look at a fantasy novel, and no the novel has nothing to do with cats as such, and yes I have a point.) I’d never had a pet when I was young, so I suddenly found myself dealing with a new range of experiences and emotions; and found also that the depictions in most media of relationships between pets and their humans were notably lacking. There’s a complexity of living with, and to an extent being responsible for, a non-human animal. You have to learn about (and sometimes worry about) diet and medical needs and what certain behaviour patterns mean. You have to learn how to communicate with a creature that does not use words — but which may be surprisingly good at understanding emotions in a voice. These sort of things are rarely shown in most stories about humans and animals, but they’re a crucial part of the experience of dealing with a pet.

A few years ago, a cat came to live with me under unexpected circumstances. (This is getting around to a look at a fantasy novel, and no the novel has nothing to do with cats as such, and yes I have a point.) I’d never had a pet when I was young, so I suddenly found myself dealing with a new range of experiences and emotions; and found also that the depictions in most media of relationships between pets and their humans were notably lacking. There’s a complexity of living with, and to an extent being responsible for, a non-human animal. You have to learn about (and sometimes worry about) diet and medical needs and what certain behaviour patterns mean. You have to learn how to communicate with a creature that does not use words — but which may be surprisingly good at understanding emotions in a voice. These sort of things are rarely shown in most stories about humans and animals, but they’re a crucial part of the experience of dealing with a pet. A couple weeks ago, I discussed one of the movies I saw at this year’s

A couple weeks ago, I discussed one of the movies I saw at this year’s  There’s been much discussion lately on Black Gate about Kickstarter: about projects

There’s been much discussion lately on Black Gate about Kickstarter: about projects