An Age of Random Portents and Incoherent Miracles – Echoes of the Goddess by Darrell Schweitzer

The Goddess is dead. The Earth is very old. The fabric of time itself has worn thin. Who knows what might be glimpsed through it? — Opharastes, After Revelation

When the Goddess who reigned over Earth died her body shattered and the pieces, resonating with her power, rained down over the world. Wherever they settled they caused great changes in both the people and the land. In some places new realities were created. In others, images of the Goddess herself appeared and lingered on for years until the dawn of a new age and the emergence of a new deity.

When the Goddess who reigned over Earth died her body shattered and the pieces, resonating with her power, rained down over the world. Wherever they settled they caused great changes in both the people and the land. In some places new realities were created. In others, images of the Goddess herself appeared and lingered on for years until the dawn of a new age and the emergence of a new deity.

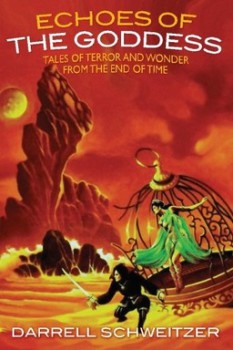

Echoes of the Goddess: Tales of Terror and Wonder From the End of Time (2012) by Darrell Schweitzer is a collection of eleven stories written over the past thirty five years and set between the earliest days of the Goddess’ death and the last days before the new age.

One of the best things to come out of reviewing books is that I’ve finally read a bunch of the authors that I somehow managed to overlook for years, despite their large catalogs and great reviews. Steve Brust and Andre Norton are two of those recent “discoveries” as is today’s author, Darrell Schweitzer.

It’s hard to fathom that I’d managed to read only two stories (“Those of the Air” in Cthulhu’s Heirs and “The Castle of Kites and Crows” in Swords Against Darkness V) by a man who has written around three hundred of the things, several novels, and numerous works of non-fiction. Nonetheless, for most of my reading life, Schweitzer existed as little more than a name I knew.

Last year, I bought his The White Isle (1980) because it was cheap, there was some mention of a comparison to Lord Dunsany, and the cover looked cool. The novel is a dark (very dark!) take on the Orpheus and Eurydice story. It’s a powerful and bleak story of love and blind obsession set in one of the most despairing worlds I’ve ever encountered. I reviewed it last year at my site and promised myself to keep my eyes open for more of Schweitzer’s work. When Echoes of the Goddess showed up as an e-book, I snagged it at once.