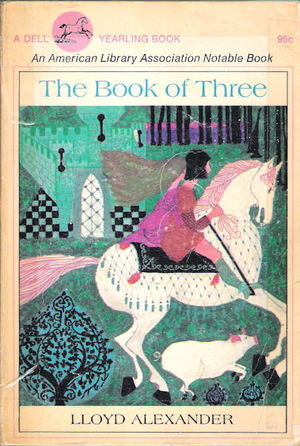

The Book of Three by Lloyd Alexander

Bear with me for a bit. With the death of Ursula K. Le Guin a few weeks ago, I began thinking about her Earthsea books. They were among the earliest non-Tolkien fantasy books I read. I loved them as a kid, I’ve read them three or four times since, and have fond memories of them. I’ll be looking at the first, A Wizard of Earthsea, next time. Thinking about those books got me thinking about a series I actually read even more times and have even fonder memories of: Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain.

Bear with me for a bit. With the death of Ursula K. Le Guin a few weeks ago, I began thinking about her Earthsea books. They were among the earliest non-Tolkien fantasy books I read. I loved them as a kid, I’ve read them three or four times since, and have fond memories of them. I’ll be looking at the first, A Wizard of Earthsea, next time. Thinking about those books got me thinking about a series I actually read even more times and have even fonder memories of: Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain.

Beginning with The Book of Three (1964), Lloyd Alexander created what has to be one of the first genre-fantasy uses of Celtic mythology (yes, Alan Garner had turned to Celtic themes in his Alderly Edge books, but those books are set in contemporary Britain, not a secondary world). Specifically, he drew on that complex and complicated compendium of Welsh tales, the Mabinogion, for inspiration and names. In this book, the four that follow, and a later collection of short stories, Alexander reworked the idiosyncratic legends into something any modern reader of fantasy would recognize immediately. Gone are the stories of women made from flowers, a human prince trading places with the god of the afterlife, and a king who is gigantic enough to wade to Ireland, and instead, a much more straightforward of a boy learning about the perils and responsibilities of heroism. Considering his intended audience was elementary school readers, it makes perfect sense to simplify, and to introduce a greater degree of coherence. I also imagine many young readers, like I was, were intrigued enough by Alexander’s books to track down the real legends.

In addition to being one of the earliest glosses on Celtic themes, The Book of Three is one of the first times Tolkien’s dark lord trope seeped into the genre. Instead of being a fairly benign lord of the afterlife as he is in the Mabinogion, Arawn is reconfigured as a mostly standard issue dark lord. The original’s mythic paradise, Annwn, is reconstructed here as a dread realm. Rereading The Book of Three for the first time in at least ten years, I was quite happy that I still enjoyed it, but seeing it with older eyes exposed gears and wires I hadn’t paid a mind to before.