Fantastic Stories of Imagination, January and February 1964: A Retro-Review

|

|

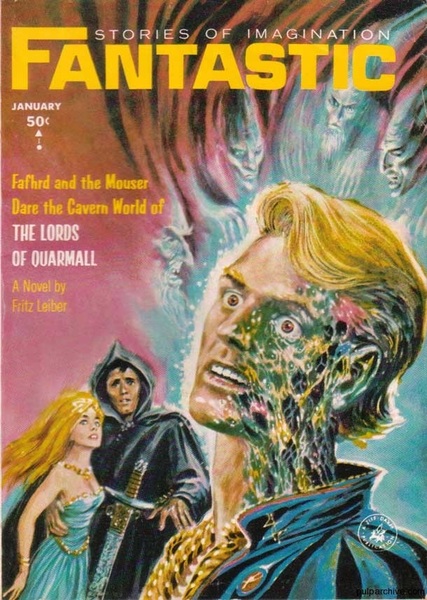

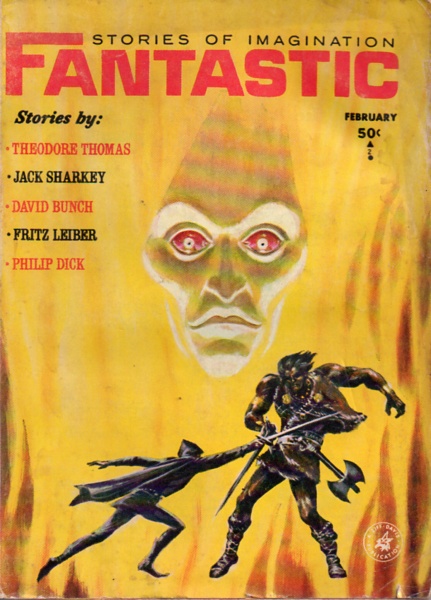

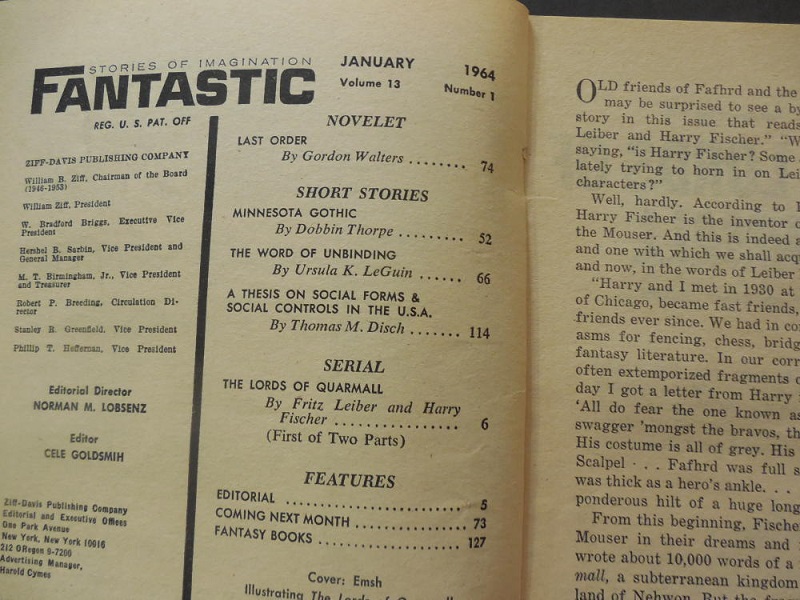

These issues are significant in that they include the serialization of a Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser novella — but not just any novella: this includes the first and nearly only contribution to the series from Leiber’s original collaborator, and supposed model for the Mouser, Harry Fischer.

Each cover is by Ed Emshwiller, and they both illustrate the serial. The interiors in January are by Emsh, Lutjens (first name perhaps Peter?), Dan Adkins, Lee Brown Coye, and Virgil Finlay. In February they are from the same folks except for Coye.

The editorials concern, in January, Harry Fischer’s role in the creation of Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser, and in February, serious research in both the US and the Soviet Union into telepathy. There is a brief book review column in January, by S. E. Cotts, in which she praises Shirley Jackson’s The Sundial very highly, and is somewhat more reserved on R. DeWitt Miller’s Stranger Than Life, one of those books about “unexplainable events.” The February issue includes a lettercol, According to You, with letters from Bill Wolfenbarger (praise for Schomburg, and for the more horrific side of fantasy), E. E. Evers (much disdain for the November 1961 issue, even for the Le Guin story), and Norman Masters (hated Sharkey’s “The Aftertime,” likes Le Guin).

The January issue also includes the annual Statement of Ownership, Management and Circulation, which states an average paid circulations figure of about 32,500 for 1963.

[Click the images to embiggen.]

The stories are as follows.

January

Serial

“The Lords of Quarmall,” First of Two Parts, by Fritz Leiber and Harry Fischer (17,000 words)

Novelet

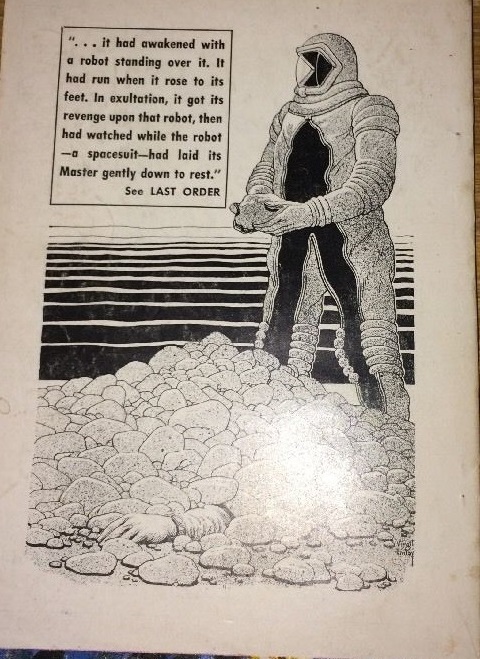

“Last Order,” by Gordon Walters (15,000 words)

Short Stories

“Minnesota Gothic,” by Dobbin Thorpe (5000 words)

“The Word of Unbinding,” by Ursula K. Le Guin (2400 words)

“A Thesis on Social Forms and Social Controls in the U.S.A.,” by Thomas M. Disch (5000 words)

February

Serial

“The Lords of Quarmall,” Conclusion, by Fritz Leiber and Harry Fischer (14,500 words)

Novelets

“Novelty Act,” by Philip K. Dick (11,500 words)

“Return to Brobdingnag,” by Adam Bradford, M.D. (7,500 words)

Short Stories

“The Soft Woman,” by Theodore L. Thomas (1,100 words)

“The Orginorg Way,” by Jack Sharkey (3,200 words)

“They Never Came Back from Whoosh!,” by David R. Bunch (1,700 words)

“Death Before Dishonor,” by Dobbin Thorpe (2,000 words)

|

|

Back covers for January and February 1964 Fantastic

Let’s discuss the three Tom Disch stories first. Three? Yes, of course, because “Dobbin Thorpe” was a pseudonym Disch used for three stories in Amazing and Fantastic — the two here, and one of his classics, “Now is Forever” (Amazing, March 1964). “Death Before Dishonor” is a brief mordant story about a somewhat loose young woman who fools around with a tattoo artist one night, and also gets a tattoo — which proves a problem when the man she’s promised to be faithful to sees it. The conclusion is horrific but a bit unconvincing — really, this is not Disch at his best at all.

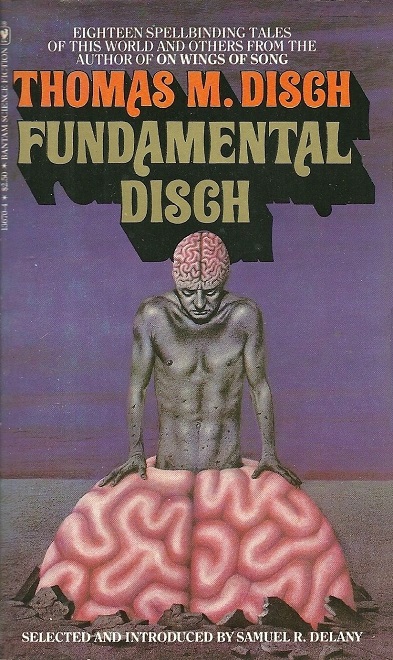

“Minnesota Gothic” is rather better. Another story in the horror mode, about a young girl who encounters a woman she becomes convinced is a witch. Especially when she finds the woman’s dead brother… not so dead. But the little girl has powers too, which in the hands of an amoral little girl might be pretty scary. “Minnesota Gothic” was reprinted in Disch’s 1980 Bantam collection, Fundamental Disch.

|

|

Finally, “A Thesis on Social Forms and Social Controls in the U. S. A.” is a mock essay supposedly produced towards the middle of the 21st Century which suggests satirically the form of society at that time, explicitly riffing on Orwell’s dicta from 1984: “Freedom is Slavery, Ignorance is Strength, War is Peace” and adding “Life is Death, Love is Hate,” with such notions as compulsory slavery every fifth year for adults aged 21 to 51. It’s a pretty decent piece of pure Dischian satire.

Finally, “A Thesis on Social Forms and Social Controls in the U. S. A.” is a mock essay supposedly produced towards the middle of the 21st Century which suggests satirically the form of society at that time, explicitly riffing on Orwell’s dicta from 1984: “Freedom is Slavery, Ignorance is Strength, War is Peace” and adding “Life is Death, Love is Hate,” with such notions as compulsory slavery every fifth year for adults aged 21 to 51. It’s a pretty decent piece of pure Dischian satire.

“A Thesis on Social Forms and Social Controls in the U. S. A.” was reprinted in 19070 in Under Compulsion (Panther UK) and in the US in Fun with Your New Head (Doubleday, 1970).

Along with Disch, these issues featured two other writers who were to one degree or another Goldsmith discoveries — that is, major writers who did much of their earliest work for Goldsmith’s magazines. One is Ursula K. Le Guin, whose “The Word of Unbinding” is a fine early fantasy about a wizard imprisoned by another evil wizard, who battles that one with the only resistance available to him: death. The other is David R. Bunch, the wildly strange writer the great bulk of whose work was very short stories for Goldsmith. “They Never Came Back from Whoosh!” is a satire on commercialism and conformity, about a place said to be wonderful that everyone must visit but no one returns from. It’s one of Bunch’s better pieces I think.

Jack Sharkey was also a Goldsmith regular, and, in my view, one of her weak spots. He really wasn’t very good — though he was professional and, I suppose, reliable in his way. “The Orginorg Way”, that said, is better than usual for Sharkey, perhaps because it’s short. It’s about an unprepossessing man obsessed with a woman, who turns to manipulation of plants as a way to attract her — with, of course, unfortunate effects.

The other short story is a short-short from Theodore L. Thomas: “The Soft Woman,” a horror story that I confess I didn’t quite get, about a man who encounters a beautiful woman and takes her to bed — with, to coin a phrase, unfortunate effects. Here Thomas was too subtle for me, I suppose — was this revenge from a briefly mentioned previous lover?

The most significant novelet, surely, is Philip K. Dick’s “Novelty Act.” This story mixes a strange set of notions, all very Dickian — the country is ruled, it seems, by an immortal First Lady (Nicole) who takes a new husband as President every four years, based partly on talent shows. There are also papoolas, natives of Mars, that everyone loves, perhaps because of their telepathic powers. And a jalopy dealer named Loony Luke with a plan to send people to Mars. And the central character, Ian Duncan, an aging resident of the Abraham Lincoln apartments, who plays classical music for a jug band and hopes to win a talent contest and meet the First Lady. Pretty weird stuff, really, and very much of the Philip Dick flavor, but perhaps, I thought, more of an undeveloped idea that could have been a novel than a truly successful novelet.

“Adam Bradford, M. D.” wrote only four stories, all for Cele Goldsmith (Lalli), between the December 1963 Fantastic and the August 1964 Fantastic. His real name was Joseph Wassersug. The stories are contemporary takes on Gulliver’s Travels, supposing that a present-day doctor (Adam Bradford) discovers Gulliver’s true memoirs, realizes that they describe real places, and manages to travel to them. The burden of each story is a satirical look at contemporary society — exactly as the burden of Swift’s original Gulliver’s Travels was a look at his contemporary society. So, “Return to Brobdingnag” has Bradford visiting Brobdingnag, where he learns the details of contemporary Brobdingnagian society, and how they differ from what Gulliver experienced, but still to the discomforture of a normal human. A minor work, really. The four stories “Bradford” published would presumably have made a reasonably coherent short book — I wonder if there was ever a plan to produce such a thing.

Finally, “Gordon Walters” was a pseudonym for English writer George Locke (b. 1936), who wrote about 7 short stories, most as by “Walters,” edited one early issue of the British critzine Vector with Michael Moorcock and others, and also wrote one strange looking novel as by “Ayresome Johns.” He is much better known for a variety of important bibliographical works, mostly in his Spectrum of Fantasy series. “Last Order” is actually pretty good, about a robot left by a criminal on a strange asteroid, with one last order, and about Haggard Pietri and Jackson McCann, once partners, until McCann went off to space and Pietri was afraid to follow him. And about insubstantial aliens. All rather old-fashioned, really, even for over 50 years ago, but kind of enjoyable.

|

|

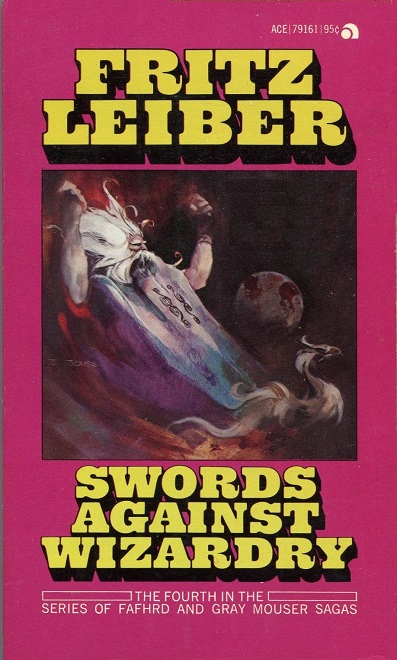

And then the serial. “The Lords of Quarmall” is a particularly interesting entry in the Fafhrd/Gray Mouser saga because, as I noted above, it was among the first stories conceived in the series, by Leiber’s friend Harry Fischer. The two had jointly imagined the heroes (Fafhrd being to some extent based on Leiber, and the Mouser on Fischer). Both began stories in 1937. Leiber’s “The Adventure of the Grain Ships” was eventually finished as “Scylla’s Daughter” and published in Fantastic in 1961. Leiber’s original version, unfinished, was published in 1997 in the New York Review of Science Fiction, as “The Tale of the Grain Ship — a Fragment.” And Leiber took Fischer’s 10,000 words of work on “The Lords of Quarmall” and finished it for this serial. (The first published Fafhrd/Grey Mouser story was “Two Sought Adventure,” in Unknown in 1939. Fischer never became a writer, really, though he did publish one more story, “The Childhood and Youth of the Gray Mouser,” in Dragon in 1978.) “The Lords of Quarmall” was reprinted in the fourth Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser collection, Swords Against Wizardry (Ace, 1968).

“The Lords of Quarmall” itself is decent work, though not by any means among the very best of the Lankhmar stories. The two heroes have been separately hired by the two sons of the current ruler of the underground realm Quarmall. The current ruler is named Quarmal, and his elder son is the sadistic Hasjarl, who rules the Upper Levels of Quarmall. Fafhrd is working for him, while the Mouser works for the sorcery-obsessed younger son, Gwaay. Each of our heroes, of course, is enamored with a pretty woman in service to Gwaay or Hasjarl, and each is motivated to save their girlfriend from the cruel caprices of their rulers. Each son is primarily concerned with getting the other out of the way so that he alone will inherit their father’s crown on the occasion of his impending death.

The first half sets all this in train, and the second half reveals what actually happens when Quarmal dies. Fafhrd and the Mouser, of course, realize that their employers are dangerous nuts, and they maneuver to at least get away with their sweethearts safely, but there is another agent with his own ideas of what needs to happen to secure the future of Quarmall. It all comes together quite nicely, with a little surprise (readily guessed but well executed). As I said — not the best of the Lankhmar stories, but quite enjoyable.

Our recent coverage of Fantastic includes:

December 1959

April 1960

January 1962

February 1962

June and July 1962

November and December 1963

January and February 1964

August and September 1964

October 1964

January 1965

June 1965

Fantastic Stories: Tales of the Weird & Wondrous, edited by Martin H. Greenberg and Patrick L. Price

Rich Horton’s last Retro Review for us was the December 1964 issue of Amazing Stories. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. See all of Rich’s retro-reviews here.

Of course I was happy to see this article, since I particularly like the retro-reviews of Fantastic issues from Golsmith/Lalli’s time. Was there anything to indicate that “The Word of Unbinding” was set in Earthsea?

No, there really isn’t any overt indication that “The Word of Unbinding” is set in Earthsea. I wonder if Le Guin already knew it was an Earthsea story at this time? There is talk of Names, which is consistent with the other early Earthsea story, “The Rule of Names”.

is 1961 typo for 1963? love Goldsmith’s mags

Jeff R

Indeed, E. E. Evers’ disdain was for the November 1963 issue, not 1961.

(“Scylla’s Daughter” did appear in 1961, however.)

[…] N (Black Gate) Fantastic Stories of Imagination, January and February 1964: A Retro-Review — “And then the serial. ‘The Lords of Quarmall’ is a particularly […]

[…] N (Black Gate) Fantastic Stories of Imagination, January and February 1964: A Retro-Review — “And then the serial. ‘The Lords of Quarmall’ is a particularly […]