The Weird of Oz gabs about Antiheroes

Antihero. A problematic term to begin with, its overuse has further watered it down. Anti- typically means to be in opposition or even to be the opposite; the antithesis of a position is the oppositional position.

Antihero. A problematic term to begin with, its overuse has further watered it down. Anti- typically means to be in opposition or even to be the opposite; the antithesis of a position is the oppositional position.

So, technically, one might interpret anti-hero to mean a villain. This is rarely, if ever, how the term is used; so what do we mean by an antihero?

Off the top of my head, without resorting to any dictionary definition, this is how I tend to picture an antihero: A person not serving any particular ideal or higher purpose, but generally self-serving, who, while going about his (or her) business in pursuit of fortune, power, pleasure, or whatever turns his crank, is suddenly confronted by a moral choice. And at that moment, not for any dogmatic or religious reasons, any creeds or codes, but simply because of some niggling inner compass — his conscience — he makes the choice that is least likely to offer personal gain, that involves self-sacrifice, that may in fact be fatal. He makes a heroic choice, the choice that allows us to continue to root for him as the hero-protagonist.

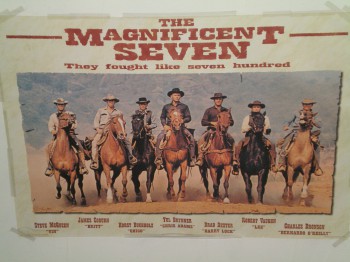

Think of the fallen samurai in The Seven Samurai or the lawless gunslingers in The Magnificent Seven. In both cases, when they learn that the threatened peasant village cannot really afford to pay them and that they are outnumbered five to one, they nevertheless decide to make a stand to protect the afflicted. No promise of financial reward and a very high probability of death — an option that the histories of these men would not suggest they would choose. They are neither knights nor saints. Yet they become heroes and, in some cases, martyrs. All appearances to the contrary, deep down they prove to be — when it really counts — good men. Or in that moment they become good men.

I’m a total fangirl around

I’m a total fangirl around