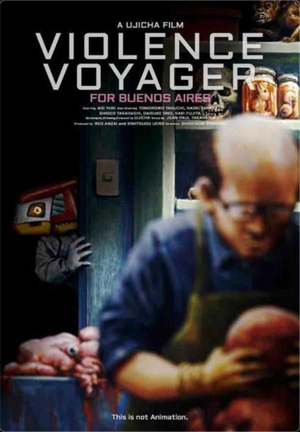

Fantasia 2018, Day 13: Violence Voyager

Late in the evening of Tuesday, July 24, I made my way to the J.A. De Sève Theatre for my one film of the day: Violence Voyager, an 83-minute animated feature by Japanese writer-director Ujicha. We follow an American schoolboy in Japan, Bobby (Aoi Yuki), as he and his friend explore some hills near his home. They find a strange, nearly-abandoned amusement park, but upon entering find themselves caught up in a terrible scheme. They and other children are captured, mutilated, mutated, and (in many cases) killed. Can Bobby free himself and others, and destroy the horrible place called Violence Voyager?

Late in the evening of Tuesday, July 24, I made my way to the J.A. De Sève Theatre for my one film of the day: Violence Voyager, an 83-minute animated feature by Japanese writer-director Ujicha. We follow an American schoolboy in Japan, Bobby (Aoi Yuki), as he and his friend explore some hills near his home. They find a strange, nearly-abandoned amusement park, but upon entering find themselves caught up in a terrible scheme. They and other children are captured, mutilated, mutated, and (in many cases) killed. Can Bobby free himself and others, and destroy the horrible place called Violence Voyager?

The first and overwhelming impression of the movie is of a dissonant strangeness. There’s a tone like a children’s story that seems destined to give way to something darker, and indeed it does, but then that darkness itself is hardly taken seriously. There’s a weird unconcern with traditional narrative effects at the same time that the structure’s remarkably tight. It’s not like much else I’ve seen, for better and worse.

Consider the animation style. It’s an unusual form called gekimation, which involves moving flat images. Lips don’t move, faces don’t shift. Shapes are moved about, and cuts give a further illusion of movement. This works better than one might think, especially once a few minutes have passed and the viewer’s assimilated the approach. Occasionally actual fluids or the like are used as visual elements as well, but mainly one watches painted pieces of paper slide over backgrounds. The art style’s intriguingly organic, with every brushstroke visible. I personally thought it was interesting without being attractive, but I can see how it could appeal more strongly to others.

As a story, there’s a sort of tension between horror and satire. It is genuinely transgressive, with all sorts of horror inflicted on children. There are genuinely surprising images here, as for example a rack of dead nude children (and the explicit nudity in some sequences is occasionally more surprising than the violence). And yet it feels muted, almost, by the thoroughgoing irony of the film. It avoids outright death-metal grotesquerie in place of its own kind of strangeness, and somehow never feels as confrontational as it seems to aim for. The early air of an optimistic children’s cartoon is never wholly abandoned, and rather than heighten the air of monstrosity, I find it functions as an alienation effect — it swathes the movie in a distancing irony, lessening the immediacy of everything we see.