Future Treasures: A Longer Fall by Charlaine Harris

|

|

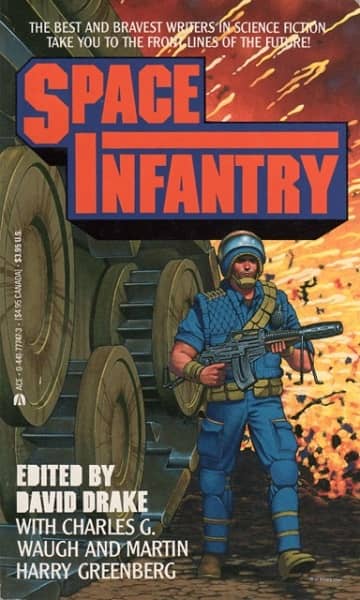

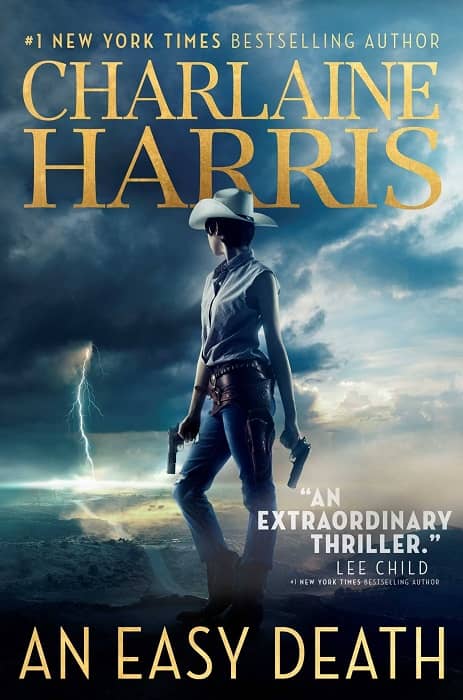

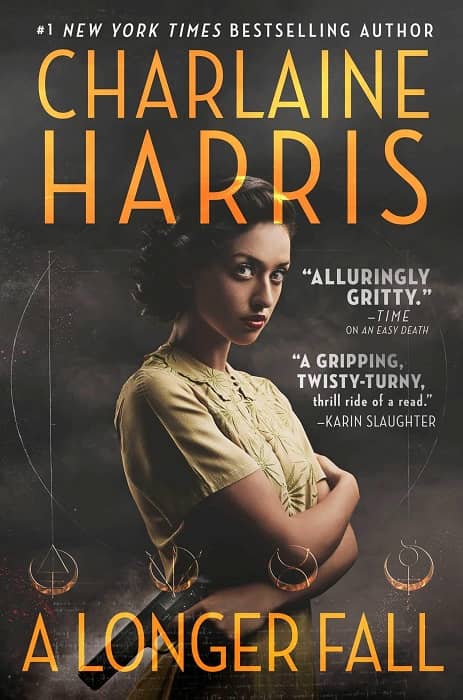

An Easy Death (October 2018) and A Longer Fall (January 2020), both from Saga Press. Covers by Colin Anderson

There aren’t enough Weird Westerns in the world, which is why I treasure them when I find ’em. Charlaine Harris (the Sookie Stackhouse novels) kicked off a promising series last year with An Easy Death, the first Gunnie Rose novel, which follows gunslinger Lizbeth Rose in the fractured countries and territories that were once the U.S. A Longer Fall, which arrives in hardcover in two weeks, sends Lizbeth to the southeast territory of Dixie on a dangerous mission. Here’s an excerpt from the enthusiastic review at Kirkus for An Easy Death.

In the opening novel of Harris’ new series, set in a dangerous and largely lawless alternate United States, a young gunslinger for hire hits the trail to track down a descendant of Rasputin.

Life isn’t easy and death is around every corner in Harris’ thrilling new adventure, in which the U.S. is a shadow of its former self. Franklin Roosevelt was assassinated before he could be sworn in, and the country was subsequently fractured: Mexico has reclaimed Texas, Canada has usurped a large swath of the northern states, and the Holy Russian Empire has taken over California… Nineteen-year-old Lizbeth Rose is a skilled gunslinger for hire, but a disastrous run-in with bandits has left her the sole survivor of her crew. After making it home, she’s approached by Paulina Coopersmith and Ilya “Eli” Savarov, two grigoris (aka wizards), who want her to help them find wizard Oleg Karkarov, who they think is a descendant of Rasputin and whose blood may be able to help their beloved czar. There’s a hitch: She tells them he’s dead but doesn’t mention that she’s the one who killed him… A refreshing and cinematic, weird Western starring a sharp-as-nails, can-do heroine. Harris’ many fans will surely follow Gunnie Rose anywhere.

A Longer Fall will be published by Saga Press on January 14, 2020. It is 304 pages, priced at $26.99 in hardcover and $12.99 in digital formats. The cover is by Colin Anderson. Read Chapter One (and details on the cover) at Paste Magazine.