Doom, Zork and Wizardry: 20th Century Retro Gaming

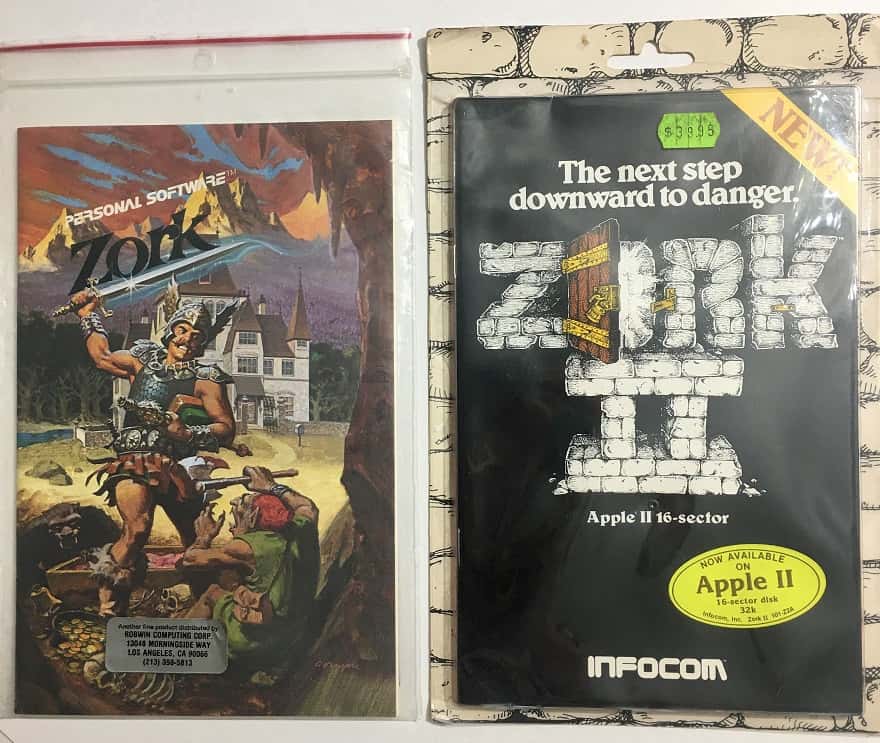

Zork and Zork II for the Apple II (Personal Software and Infocom)

Back in the day, I used to play a lot of computer games. And to be honest, I still spend a fair amount of time each week playing, though these days it’s pretty much limited to Lord of the Rings Online.

I started out in the late 1970’s on the Apple II computers in our high school or at the houses of a few of my friends who were lucky enough to have a computer. I bought my first computer, a Commodore 64, when I went to college in 1981, and played a variety of games on it. I particularly remember Wizard of Wor, which was a port from the arcade game that I loved (my friends and I spent a lot of time, and quarters, in arcades during this period).

Later on, after I’d move to a Windows PC, my wife and I, along with a group of friends and family, used to play a lot of first-person shooters, such as Doom, Duke Nukem, Heretic, Hexen, Day of Defeat, Call of Duty and many others. To this day, several of my nephews and nieces still sometimes address me as Duke, a shortened form of the in-game nickname I used in the multi-player games (and no, it had nothing to do with Duke Nukem, but rather was inspired by David Bowie).

When Deb and I went to law school in 1985, we quickly found one of Cambridge’s top attractions (at least if you were a science fiction fan!). This was the Science Fantasy Bookstore, which was owned and run by Bruce “Spike” MacPhee. We used to visit the bookstore quite a bit during the three years we lived there, and always enjoyed talking with Spike, who was a passionate and knowledgeable SF fan. Spike had founded the bookstore in 1977 and it stayed open until 1989.

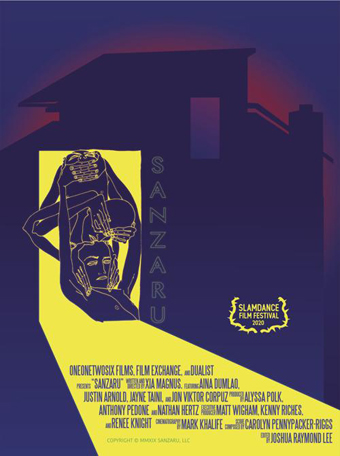

The Japanese image of the three wise monkeys is as early as the 16th century: one monkey with hands over eyes, the next with hands over ears, the third with hands over mouth. See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil; thus the monkeys’ names, Mizaru, Kikazaru, and Iwazaru, ‘not-seeing,’ ‘not-hearing,’ and ‘not-speaking.’ There’s a pun in Japanase on zaru, not, and saru, monkey, so collectively the trio’s simply ‘three monkeys,’ or sanzaru.

The Japanese image of the three wise monkeys is as early as the 16th century: one monkey with hands over eyes, the next with hands over ears, the third with hands over mouth. See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil; thus the monkeys’ names, Mizaru, Kikazaru, and Iwazaru, ‘not-seeing,’ ‘not-hearing,’ and ‘not-speaking.’ There’s a pun in Japanase on zaru, not, and saru, monkey, so collectively the trio’s simply ‘three monkeys,’ or sanzaru.

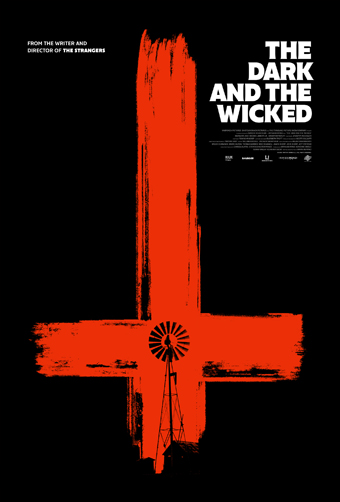

By Day 10 of Fantasia I’d started to skip the panels and special presentations. They all looked interesting to greater or lesser degrees, but while the movies were only available while the festival was still going on, the panels would stay up afterward. Still, Day 10 was an exception, with my schedule free for a panel I was particularly interested in: “New York State Of Horror,” hosted by author Michael Gingold. It took a look at how and when New York City became a setting for horror films — something unusual in the early decades of filmmaking, when horror was typically set in ancient European locales. King Kong (1933) was an obvious exception, but Gingold observed that Rosemary’s Baby was the real trail-blazer for New York horror stories in film, followed in the 70s and 80s by more tales of urban terror. It was a good discussion, with contributions from directors Bill Lustig and Larry Fessenden (

By Day 10 of Fantasia I’d started to skip the panels and special presentations. They all looked interesting to greater or lesser degrees, but while the movies were only available while the festival was still going on, the panels would stay up afterward. Still, Day 10 was an exception, with my schedule free for a panel I was particularly interested in: “New York State Of Horror,” hosted by author Michael Gingold. It took a look at how and when New York City became a setting for horror films — something unusual in the early decades of filmmaking, when horror was typically set in ancient European locales. King Kong (1933) was an obvious exception, but Gingold observed that Rosemary’s Baby was the real trail-blazer for New York horror stories in film, followed in the 70s and 80s by more tales of urban terror. It was a good discussion, with contributions from directors Bill Lustig and Larry Fessenden (

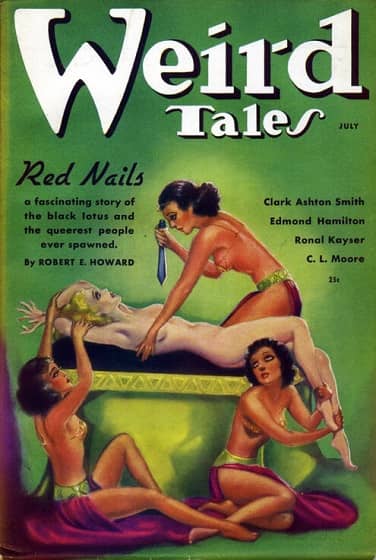

‘Weird’ is less of a concrete descriptor than might at first appear. There are multiple subcategories of weird, and different things called weird can produce very different experiences. This is especially so when a work of weirdness mixes different weird things.

‘Weird’ is less of a concrete descriptor than might at first appear. There are multiple subcategories of weird, and different things called weird can produce very different experiences. This is especially so when a work of weirdness mixes different weird things.

One of the fascinating things about art is the way it speaks to its exact moment. That’s even more fascinating with film, which has such a long gestation time; write a movie, shoot the movie, then edit the movie and work on it in postproduction, and it’ll come out years after it was conceived. Which is why it was fascinating to see so many films at this year’s Fantasia that revolved around haunted houses. Occasionally the haunted building might be something like a school (as in

One of the fascinating things about art is the way it speaks to its exact moment. That’s even more fascinating with film, which has such a long gestation time; write a movie, shoot the movie, then edit the movie and work on it in postproduction, and it’ll come out years after it was conceived. Which is why it was fascinating to see so many films at this year’s Fantasia that revolved around haunted houses. Occasionally the haunted building might be something like a school (as in