Fantasia 2020, Part XXIV: Milocrorze – A Love Story

‘Weird’ is less of a concrete descriptor than might at first appear. There are multiple subcategories of weird, and different things called weird can produce very different experiences. This is especially so when a work of weirdness mixes different weird things.

‘Weird’ is less of a concrete descriptor than might at first appear. There are multiple subcategories of weird, and different things called weird can produce very different experiences. This is especially so when a work of weirdness mixes different weird things.

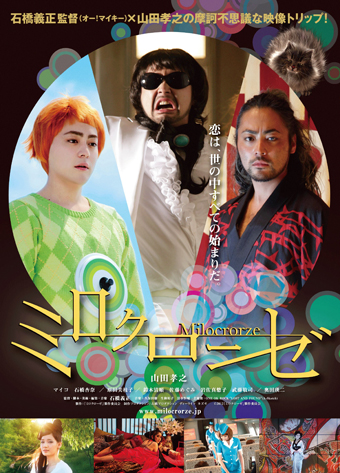

Thus Milocrorze – A Love Story (Mirokurôze, ミロクローゼ), a 2011 film written and directed by video and performance artist Yoshimasa Ishibashi. The winner of Fantasia’s awards for best director and most innovative feature film in the year it premiered, it was revived for this year’s festival, where I saw it for the first time. It is not like most other films, for both better and worse.

It begins by following a boy named Ovreneli Vreneligare who lives in a brightly-coloured eye-popping wonderland with a talking cat, and who falls in love with a woman named Milocrorze (Maiko). He hatches a plan to seduce her, it briefly works, and then things go astray. This leads to a dramatic shift in tone, as the movie leaves him to follow a TV huckster named Besson Kumagai claiming to give young men infallible relationship advice; the first of three roles played by Takayuki Yamada, Kumagai’s a 70’s lounge lizard who bursts into dance routines at odd moments. While dancing behind the wheel of a car, he blows into a group of people, and then we leave Kumagai and start following one of them.

Specifically, we follow a wandering samurai named Tamon (Yamada) who is seeking his lost true love. This becomes the longest part of the film, as we follow Tamon in and out of flashbacks (and through a tattoo studio featuring renowned director Seijun Suzuki in an extended cameo part) to a climactic fight sequence in a brothel and gambling den. Then we return to Ovreneli Vreneligare, now an adult played by Yamada, as he finds Milocrorze again.

You can look at the connections between these stories in a number of ways, but the first thing that has to be said is that the movie is consistently pleasurable to look at, in at least three different tones. Ovreneli Vreneligare’s candy-coloured dreamland is the most striking. The hyperactive modern world of Kumagai is a needed burst of energy. Then that’s followed by the melodramatic, weirdly-lit, deeply artificial world of Tamon, centred around its extended fight scene that drops in and out of slow and fast motion. There’s always something happening in this movie.

One of the fascinating things about art is the way it speaks to its exact moment. That’s even more fascinating with film, which has such a long gestation time; write a movie, shoot the movie, then edit the movie and work on it in postproduction, and it’ll come out years after it was conceived. Which is why it was fascinating to see so many films at this year’s Fantasia that revolved around haunted houses. Occasionally the haunted building might be something like a school (as in

One of the fascinating things about art is the way it speaks to its exact moment. That’s even more fascinating with film, which has such a long gestation time; write a movie, shoot the movie, then edit the movie and work on it in postproduction, and it’ll come out years after it was conceived. Which is why it was fascinating to see so many films at this year’s Fantasia that revolved around haunted houses. Occasionally the haunted building might be something like a school (as in

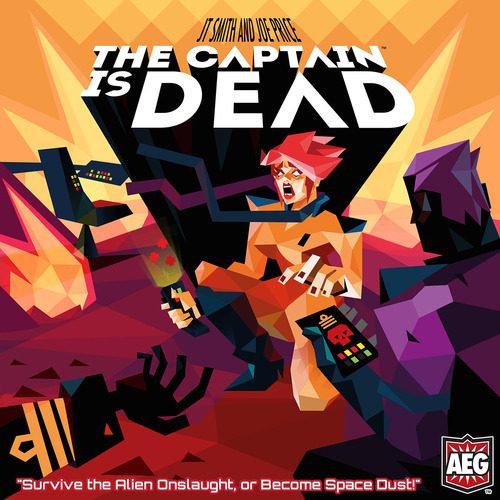

Anyone else feel like we’re living in a Golden Age of board games? Or have I just been playing more because of COVID? We’re spoiled. Gone are the days of cutting out your own cardboard counters and coloring in your own dice with a crayon.

Anyone else feel like we’re living in a Golden Age of board games? Or have I just been playing more because of COVID? We’re spoiled. Gone are the days of cutting out your own cardboard counters and coloring in your own dice with a crayon.  Day 9 of Fantasia began for me with The Block Island Sound. Directed by brothers Kevin and Matthew McManus, and written by Matthew, it’s a horror movie named for a body of water off the coast of Rhode Island. It’s the rare horror story that deals with inhuman mysteries on the northeastern coast of the United States while not feeling Lovecraftian at all.

Day 9 of Fantasia began for me with The Block Island Sound. Directed by brothers Kevin and Matthew McManus, and written by Matthew, it’s a horror movie named for a body of water off the coast of Rhode Island. It’s the rare horror story that deals with inhuman mysteries on the northeastern coast of the United States while not feeling Lovecraftian at all.

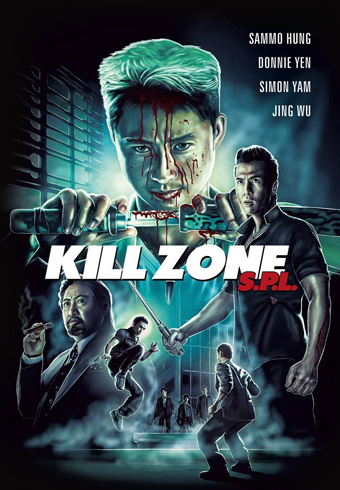

One of the lovely things about covering Fantasia is the chance to see genre classics I missed the first time around, often brought back to the screen in a restored version. Again in 2020, notwithstanding its streaming-only nature, Fantasia revived a number of great films from prior years. While my own inefficiency with scheduling meant I ended up missing Johnnie To’s A Hero Never Dies, I saw many of the others, including Wilson Yip’s 2005 movie SPL: Kill Zone (also just Kill Zone, originally SPL: Sha Po Lang, 殺破狼).

One of the lovely things about covering Fantasia is the chance to see genre classics I missed the first time around, often brought back to the screen in a restored version. Again in 2020, notwithstanding its streaming-only nature, Fantasia revived a number of great films from prior years. While my own inefficiency with scheduling meant I ended up missing Johnnie To’s A Hero Never Dies, I saw many of the others, including Wilson Yip’s 2005 movie SPL: Kill Zone (also just Kill Zone, originally SPL: Sha Po Lang, 殺破狼).