Elf Opera in Tang China

Matthew Surridge’s fascinating post on specificity in setting got the various gears, levers, in pistons in my head working. I’m currently writing this in a cloud of steam gushing out both ears, and hopefully I’ll be able to finish before the gnomes who power the mechanisms of my consciousness go on strike.

The short version: Matthew, I agree completely. There is a certain charm to what I think of as the typical D&D setting, in which castles are built out of clichés mortared together with anachronisms, and the world is a playground of exotic sights for the mismatched band of adventurers to wander among and slay monsters in. It’s a lot of fun in a game–and sometimes fun in a D&D novel–but it lacks the kind of verisimilitude that makes a story really engrossing.

I tend to think that the richness of real-world Medieval civilization is masked by a series of misconceptions and broad generalizations, beginning with the tendency to see them as one long Dark Age spanning from the Fall of Rome to the Protestant Reformation. But the so-called Dark Ages were home to the kingdoms of Charlemagne and Alfred, the flourishing of Irish and Italian monasticism, and the first sparks of the most vibrant intellectual life the world had yet seen. Likewise, the High Middle Ages were an age of soaring cathedrals, vibrant art and music, and universities that studied everything from Roman law to medicine.

At the same time, the European Middle Ages were anything but homogenous. The time period covers over a thousand years, which contain literally hundreds of distinct peoples and cultures. The Vikings who besieged Paris later became the Normans who conquered England and ruled Sicily. The balance between monarchs, emperor, and papacy was constantly shifting, sometimes responding to new threats or influences, as when the Mongols crashed against the armies of the Holy Roman Emperor.

The new

The new  Master of Devils

Master of Devils

Sohaib Awan at Fictional Frontiers interviews Black Gate Managing Editor Howard Andrew Jones on his first novel The Desert of Souls, non-Western fantasy, juggling modern expectations in historical fiction, and much more:

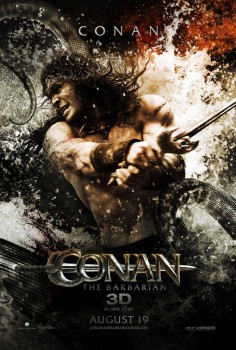

Sohaib Awan at Fictional Frontiers interviews Black Gate Managing Editor Howard Andrew Jones on his first novel The Desert of Souls, non-Western fantasy, juggling modern expectations in historical fiction, and much more: I’ve refrained from talking about Conan the Barbarian (2011) until now, despite my love for Robert E. Howard’s works. But now that we’re poised on the eve of its U.S. release, I thought I’d weigh in with my personal hopes—and fears—regarding the film.

I’ve refrained from talking about Conan the Barbarian (2011) until now, despite my love for Robert E. Howard’s works. But now that we’re poised on the eve of its U.S. release, I thought I’d weigh in with my personal hopes—and fears—regarding the film.

Sunday was the fiftieth anniversary of the death of Clark Ashton Smith. We morbid fans of a writer with a delectable taste for morbidity love to celebrate death anniversaries as much as birth ones, and the seduction of the half-century mark is too great to dismiss.

Sunday was the fiftieth anniversary of the death of Clark Ashton Smith. We morbid fans of a writer with a delectable taste for morbidity love to celebrate death anniversaries as much as birth ones, and the seduction of the half-century mark is too great to dismiss. Fantasy fiction is very often set either in the European Middle Ages, or in lands that are intentionally highly reminiscent of the Middle Ages in terms of technology and social structure. It is true that the use of European medieval settings is less common now than it has been, and also true that there have always been counter-examples. But it seems that much fantasy still relies on the European Middle Ages to define itself, one way or another. Sadly, one often has a sense that these backgrounds are not wholly thought-through; not realised as completely as they might be. The setting in a lot of fantasy, particularly I think in commercial fantasy fiction, seems to be a very generic Middle Ages in which medieval stereotypes mix with unexamined modern assumptions.

Fantasy fiction is very often set either in the European Middle Ages, or in lands that are intentionally highly reminiscent of the Middle Ages in terms of technology and social structure. It is true that the use of European medieval settings is less common now than it has been, and also true that there have always been counter-examples. But it seems that much fantasy still relies on the European Middle Ages to define itself, one way or another. Sadly, one often has a sense that these backgrounds are not wholly thought-through; not realised as completely as they might be. The setting in a lot of fantasy, particularly I think in commercial fantasy fiction, seems to be a very generic Middle Ages in which medieval stereotypes mix with unexamined modern assumptions.