Black Gate Interviews James L. Sutter, Part One

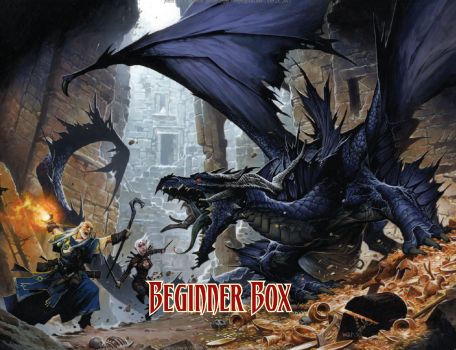

I recently caught up with Paizo’s James Sutter for a conversation about his work heading up Pathfinder’s new fiction line, as well as his own writing and influences. In part one of our conversation James tells us about his new novel for Pathfinder, Death’s Heretic, and sheds a little light on one of fantasy’s gray areas. Over the next two weeks we’ll be covering a range of topics as James divulges on media-tie in fiction, early reading, assembling the killer lineup of the Before They Were Giants anthology, working in the game industry, and turning off the ‘editorial eye.’

I recently caught up with Paizo’s James Sutter for a conversation about his work heading up Pathfinder’s new fiction line, as well as his own writing and influences. In part one of our conversation James tells us about his new novel for Pathfinder, Death’s Heretic, and sheds a little light on one of fantasy’s gray areas. Over the next two weeks we’ll be covering a range of topics as James divulges on media-tie in fiction, early reading, assembling the killer lineup of the Before They Were Giants anthology, working in the game industry, and turning off the ‘editorial eye.’

A Conversation with James L. Sutter

Death’s Heretic is your first published novel, so that seems like a pretty good place to begin the conversation. Tell us a bit about the book and about Salim, Death’s Heretic’s protagonist.

First off, Death’s Heretic is a Pathfinder Tales novel, which means that it’s set in the campaign setting for the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game. Fortunately for me, while it’s a shared-world novel, it’s a shared world that I’ve been helping to create over the last several years, and I had a lot of free reign with regard to the book’s setting.

The book is a fantastical mystery set in the desert nation of Thuvia, where folks with enough money can bid on an extremely rare potion which acts like a fountain of youth. A lot of people will do anything for a few more years of life and youth, so it’s not too surprising when one particular merchant wins the annual auction and winds up assassinated. The surprising part comes when the priests of Pharasma, the death goddess, go to resurrect him, only to find that his soul’s been stolen from the afterlife by an unknown kidnapper, who’s offering to ransom the soul back for the merchant’s dose of the elixir.

That’s where Salim comes in. A former priest-hunting atheist, Salim hates the death goddess with a passion, yet is bound against his will to act as a problem-solver and hired sword for the church. In this case, he’s in for even more aggravation than usual, as the investigation is being financed by the merchant’s headstrong daughter, who demands to accompany him. Together, the two of them end up traveling all over the various planes of the afterlife in a race to uncover the missing soul, interacting with demons, angels, fey lords, mechanical warriors, and more.

At the risk of spoilers, to me the book is actually three stories: the mystery of the stolen soul, the story of how a staunch atheist ends up working for a goddess, and the colliding worlds of the hard-bitten warrior and the wealthy aristocrat.

Immortals (2011)

Immortals (2011) Young adult fiction has a lot going for it in recent years. In the wake of the Harry Potter craze, there’s an entire generation of young people who have grown up with the understanding that reading is a cool way to spend your time and entertain yourself.

Young adult fiction has a lot going for it in recent years. In the wake of the Harry Potter craze, there’s an entire generation of young people who have grown up with the understanding that reading is a cool way to spend your time and entertain yourself. Writing about Romanticism has gotten me started thinking about forms, and conventions, and how we read a story. To some extent I’ve come to feel that contemporary ways of reacting to narrative are more classical than romantic; they’re more to do with structure and form than with trusting the individual genius. It seems to me that many readers, and critics, have become used to looking for certain things in a story, and have come to think of stories that function in a different manner as necessarily defective rather than distinct. And I feel this is a pity, since if we can’t accept the strange works of genius that succeed in defiance of everything we think we know about storytelling, then our experience of story becomes diminished.

Writing about Romanticism has gotten me started thinking about forms, and conventions, and how we read a story. To some extent I’ve come to feel that contemporary ways of reacting to narrative are more classical than romantic; they’re more to do with structure and form than with trusting the individual genius. It seems to me that many readers, and critics, have become used to looking for certain things in a story, and have come to think of stories that function in a different manner as necessarily defective rather than distinct. And I feel this is a pity, since if we can’t accept the strange works of genius that succeed in defiance of everything we think we know about storytelling, then our experience of story becomes diminished.

The November issue of Clarkesworld is currently

The November issue of Clarkesworld is currently