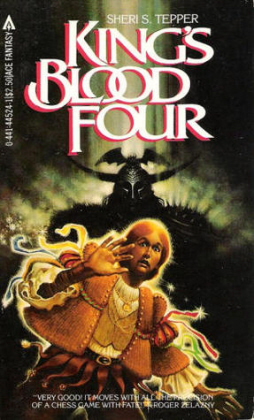

A Review of Jhereg by Steven Brust

Jhereg

Jhereg

By Steven Brust

Ace (224 pages, $2.50, April 1983)

I’ve played in a lot of tabletop RPGs, including a couple of homebrewed systems and homebrewed worlds. I’ve never encountered one that goes into the culture-changing potential of resurrection, though. It’s treated as an acceptable break from reality, a way to keep things fun, one that has little effect on the world besides providing a way for the campaign’s archnemesis to keep coming back.

Jhereg, by Steven Brust, the first book in his 12-volume Vlad Taltos series, takes the notion of reliable magical resurrection and creates a society around it.

Vlad Taltos is an Easterner and a gentleman, which isn’t a common combination. Easterners are an underclass compared to Dragaerans. The Dragaeran clan called House Jhereg allows anyone, even Easterners, to buy in — a distinct advantage, since it allows them access to the Dragaeran Empire’s sorcery. Unfortunately, the Jheregs may be the most egalitarian family in the Empire, but they also operate a lot like the mafia. Citizenship is not cheap.

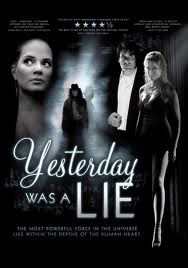

“Yesterday Was A Lie” is an indie film that indulges in experimental exposition right out of the gate.

“Yesterday Was A Lie” is an indie film that indulges in experimental exposition right out of the gate.

Two weeks ago I

Two weeks ago I  The episode opens with a young man (Robert), dressed all in black and wearing too much product in his hair, romances a girl (Kristen) in a bar. He is enigmatic and tentative, recoiling at the sight of blood from a papercut. “We can’t be together,” he says. “You think you know me, but you don’t. I’ve done bad things. You should run. Now.”

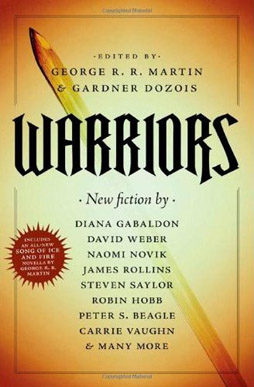

The episode opens with a young man (Robert), dressed all in black and wearing too much product in his hair, romances a girl (Kristen) in a bar. He is enigmatic and tentative, recoiling at the sight of blood from a papercut. “We can’t be together,” he says. “You think you know me, but you don’t. I’ve done bad things. You should run. Now.” Warriors, edited by George RR Martin & Gardner Dozois

Warriors, edited by George RR Martin & Gardner Dozois