Dracula’s Daughter: From Script to Screen

The success of Universal’s Dracula (1931) starring Bela Lugosi made not only a cycle of similar horror films inevitable, it virtually demanded the studio turn their attention to a direct sequel.

As had happened with Lon Chaney in the silent era, MGM was quick to top Universal at its own game. They secured the services of Lugosi and director Tod Browning for a remake of Chaney’s silent classic, London After Midnight (1927). Browning had directed that notorious lost classic and having Lugosi fill Chaney’s shoes as the faux vampire seemed an inspired choice.

As had happened with Lon Chaney in the silent era, MGM was quick to top Universal at its own game. They secured the services of Lugosi and director Tod Browning for a remake of Chaney’s silent classic, London After Midnight (1927). Browning had directed that notorious lost classic and having Lugosi fill Chaney’s shoes as the faux vampire seemed an inspired choice.

Browning’s remake, Mark of the Vampire would wing its way to theaters in 1935. Joining Lugosi’s Count Mora was Carroll Borland as his incestuous daughter, Luna. Borland was heavily featured in publicity photos with Lugosi despite not having much of an acting career (the following year she was reduced to a bit part in the first of Buster Crabbe’s Flash Gordon serials for Universal), but her portrayal of Luna was enormously influential on the cinematic female vampires who followed.

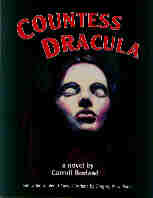

Borland contributed more than just the definitive screen depiction of a female vampire, however. Several years before Mark of the Vampire was born, she began a longstanding (and allegedly unconsummated) relationship with Bela Lugosi. She remained obsessed with the actor long after his death and had written a lengthy treatment for a Dracula sequel to star both of them entitled Countess Dracula.

Philip J. Riley published the final version of the treatment (which Borland tinkered with for decades) as part of his MagicImage FilmBooks series dedicated to Universal Horrors. Lugosi tried and failed to have the treatment produced on stage or on screen as a legitimate sequel. It remains Borland’s only writing credit and was published just after the former actress’ death in 1994.

Philip J. Riley published the final version of the treatment (which Borland tinkered with for decades) as part of his MagicImage FilmBooks series dedicated to Universal Horrors. Lugosi tried and failed to have the treatment produced on stage or on screen as a legitimate sequel. It remains Borland’s only writing credit and was published just after the former actress’ death in 1994.

Long before literary sequels to Bram Stoker’s classic vampire novel were a legal possibility, the author’s widow published an excised chapter of the novel as the title story to a posthumous collection of his short fiction entitled Dracula’s Guest in 1914.

David O. Selznick optioned the story from Florence Stoker for MGM shortly after the release of Universal’s Dracula. This was a masterstroke on Selznick’s part as he bought the rights with the clear intention of selling them at a substantial profit to Universal.

Legally, MGM could not have produced a Dracula film and Selznick paid out $500 (promising Mrs. Stoker a further $4,500 upon production) for rights he subsequently sold to Universal for $12,000. A wise investment for what was an inevitable sequel to Universal’s monster hit.

Universal quickly hired Dracula playwright, John L. Balderston to draft a treatment for the sequel, Dracula’s Daughter in January 1934. Balderston’s draft incorporates much of Stoker’s original novel that was not included in the earlier film version, precious little of “Dracula’s Guest,” and most interestingly, elements from Borland’s unproduced Countess Dracula treatment.

Universal quickly hired Dracula playwright, John L. Balderston to draft a treatment for the sequel, Dracula’s Daughter in January 1934. Balderston’s draft incorporates much of Stoker’s original novel that was not included in the earlier film version, precious little of “Dracula’s Guest,” and most interestingly, elements from Borland’s unproduced Countess Dracula treatment.

From Stoker’s excised chapter, the character of Countess Dolingen (one of Dracula’s brides) becomes Dracula’s daughter, Countess Szekeley (the real name for Romanian nobles mentioned in Stoker’s novel).

Surprisingly, Balderston determined to use some of the more shocking elements of Stoker’s book (such as Dracula’s brides being fed a kidnapped infant in a sack). The screenwriter’s notes for the studio make it clear that the envelope was to be pushed in terms of sex and violence to rival the limits Cecil B. DeMille enjoyed with his Biblical epics. Balderston also intended to restore Stoker’s story structure by bringing the climax back to Castle Dracula in Transylvania.

Balderston settled on bringing back the heroes of Dracula: Professor Van Helsing, Jonathan Harker, Mina Harker, and Dr. Seward along with introducing two new protagonists, Lord Edward Wadhurst (derived from the novel’s Lord Godalming), Helen Swaythling, and Chester Morris (derived from the novel’s Quincey Morris). Neither Lord Godalming nor Quincey Morris had made a successful transition to the screen in Tod Browning’s film adaptation of Stoker’s 1897 novel.

R. C. Sherriff developed a screenplay from Balderston’s treatment in September 1935 for director James Whale. Sherriff’s script borrows even more elements from Borland’s treatment (much of which would later be recycled for the second of Christopher Lee’s appearances as the vampire for Hammer Studios in 1965’s Dracula, Prince of Darkness).

R. C. Sherriff developed a screenplay from Balderston’s treatment in September 1935 for director James Whale. Sherriff’s script borrows even more elements from Borland’s treatment (much of which would later be recycled for the second of Christopher Lee’s appearances as the vampire for Hammer Studios in 1965’s Dracula, Prince of Darkness).

Many film historians place an emphasis on the camp aspects of the script and believe they would never have escaped the censor’s red pen. The camp elements are certainly there, but the dialogue (which runs from witty to laugh out loud funny) is no more outrageous than the dialogue in Whale’s earlier horror sequel, The Bride of Frankenstein (1935).

Interestingly, Sherriff intended to open the picture with a lengthy prologue allowing Bela Lugosi to reprise his famous role. Dracula and his daughter are given an origin story. A subsequent rewrite shortened this sequence and removed Dracula’s origin while still serving to introduce his daughter. By the time the picture reached the screen (after Garrett Fort’s rewrite), Dracula and Lugosi were out of the picture altogether.

Sherriff’s new protagonists are a quartet of Americans (brothers and sisters who have fallen in love with each other’s best friend) who visit Castle Dracula: John and Joan Martin and David and Helen Hartley. Their friend Tom Morris (Chester Morris in Balderston’s treatment) and Professor Van Helsing are retained.

Countess Szekeley is now Countess Szelenski and is portrayed more as a vamp in the Theda Bara tradition once the setting moves from Transylvania to contemporary London. Sherriff followed Balderston’s lead in incorporating much of Stoker’s novel that Garrett Fort had deleted from his screenplay to the 1931 classic.

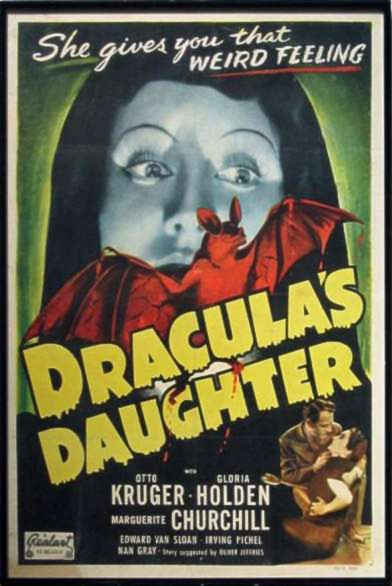

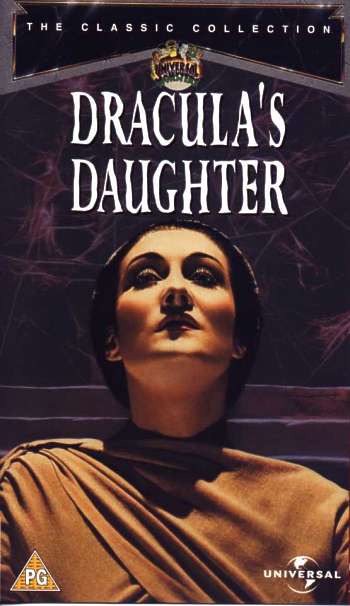

Ironically, it is Fort who would rewrite Sherriff’s script for director Lambert Hillyer once Dracula’s Daughter made it to the silver screen in 1936. Gloria Holden was cast as Countess Marya Zaleska (as Dracula’s daughter was finally known). She retains the mysterious manservant from Balderston’s treatment (actually based on a proposed mute servant of Dracula’s that Stoker excised from his novel prior to publication), Sandor. The hero is now Dr. Jeffrey Garth (Otto Kruger). Edward Van Sloan returned, as long intended, to reprise his role as Professor Van Helsing (who became Von Helsing in a continuity error in Hillyer’s film). Marguerite Churchill and Nan Grey portrayed Helen and Lili, respectively.

Ironically, it is Fort who would rewrite Sherriff’s script for director Lambert Hillyer once Dracula’s Daughter made it to the silver screen in 1936. Gloria Holden was cast as Countess Marya Zaleska (as Dracula’s daughter was finally known). She retains the mysterious manservant from Balderston’s treatment (actually based on a proposed mute servant of Dracula’s that Stoker excised from his novel prior to publication), Sandor. The hero is now Dr. Jeffrey Garth (Otto Kruger). Edward Van Sloan returned, as long intended, to reprise his role as Professor Van Helsing (who became Von Helsing in a continuity error in Hillyer’s film). Marguerite Churchill and Nan Grey portrayed Helen and Lili, respectively.

The finished film, Sherriff’s unproduced script, Balderston’s treatment, and Borland’s unproduced and unauthorized treatment for Countess Dracula share as many similarities as differences and make for a fascinating study of how elements from Stoker’s novel were reconfigured to form the basis of not only the first Dracula sequel, but many other vampire films that followed.

Philip J. Riley’s Alternate History of Filmonsters Series of Lost Scripts for BearManor Media recently published R. C. Sherriff’s script together with Balderston’s treatment as James Whale’s Dracula’s Daughter. Like Riley’s earlier publication of Carroll Borland’s Countess Dracula, the title is essential to anyone who loves Stoker’s vampire lord and is interested in the history of Universal Horrors.

William Patrick Maynard was authorized to continue Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu thrillers beginning with The Terror of Fu Manchu (2009; Black Coat Press). He is currently working on a sequel, The Destiny of Fu Manchu as well as The Occult Case Book of Sherlock Holmes. To see additional articles by William, visit his blog at SetiSays.blogspot.com

[…] Dracula’s Daughter: From Script to Screen (2010) […]

“It’s beautiful and delicate- more than anything else I loved the tragic portrayal of Dracula’s daughter as the troubled creature who abhorred killing but was driven to it by necessity!” as the late Anne Rice observed of this 1936 film which although it initially attracted little attention at the time became a “cult classic” in later decades, inspiring the likes of reluctant bloodsuckers such as Barnabas Collins in “Dark Shadows” Marvel Comics’s Morbius, even Geraint Wyn Davies in the 1990s TV drama “Forever Knight”!