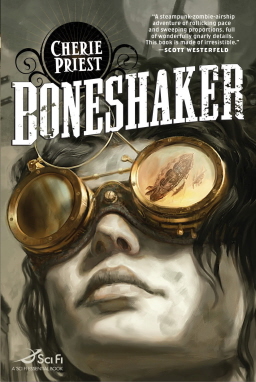

Steampunk Spotlight: Cherie Priest’s Boneshaker

One of the most popular steampunk books of the last few years, Boneshaker (Amazon, B&N) melded some of the most popular genre elements of steampunk and the zombie apocalypse wave of fiction. In this review from Black Gate #15, I commented that the book was a little action-heavy, full of zombie chases that didn’t always translate well on the printed page. I compared it to a George Romero film … and it turns out that someone took that to heart, because it’s being made into a film. I don’t normally go to zombie movies, but I’ll definitely make an exception for this one, which may well be the most visually-stunning zombie film ever.

One of the most popular steampunk books of the last few years, Boneshaker (Amazon, B&N) melded some of the most popular genre elements of steampunk and the zombie apocalypse wave of fiction. In this review from Black Gate #15, I commented that the book was a little action-heavy, full of zombie chases that didn’t always translate well on the printed page. I compared it to a George Romero film … and it turns out that someone took that to heart, because it’s being made into a film. I don’t normally go to zombie movies, but I’ll definitely make an exception for this one, which may well be the most visually-stunning zombie film ever.

Boneshaker

Cherie Priest

Tor (416 pp, $15.99, 2009)

Reviewed by Andrew Zimmerman Jones

Steampunk is traditionally set in a Victorian urban environment, with a veneer of gentility that covers a darker underbelly. And steampunk almost always includes airships (or at least flying bicycles)… often with air pirates in tow.

The weird west mythos, on the other hand, represents the frontier. While technology is usually central to steampunk, the weird west is often defined by some sort of monster (frequently zombies), but these elements can cross genres. The 1999 Will Smith film Wild Wild West featured a flying bicycle and a giant robotic spider, firmly placing it in the camp of steampunk by most accounts, but containing many weird west elements.

Boneshaker takes many of these staples, puts them in a blender, and sets to mix. It is set in a modified 1880’s Seattle, which has been walled off because a gas drifting out of the ground turns people into zombies.

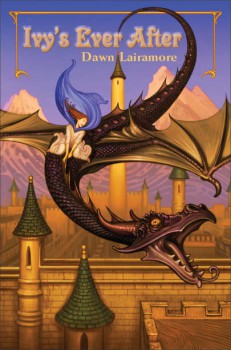

Ivy’s Ever After

Ivy’s Ever After

Problem is, that’s not what Alan came to hear. Which results in tragedy (you are reading a dark horror magazine so why would you expect anything less?) that may, or may not, have been easily foreseen.

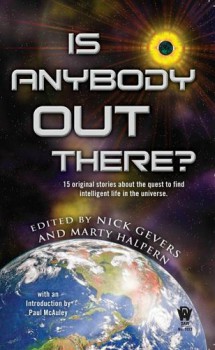

Problem is, that’s not what Alan came to hear. Which results in tragedy (you are reading a dark horror magazine so why would you expect anything less?) that may, or may not, have been easily foreseen. Is Anybody Out There?

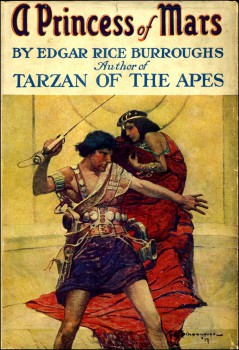

Is Anybody Out There? I played a bit rough with A Princess of Mars last week in my

I played a bit rough with A Princess of Mars last week in my

Conspirator

Conspirator Shadow Prowler

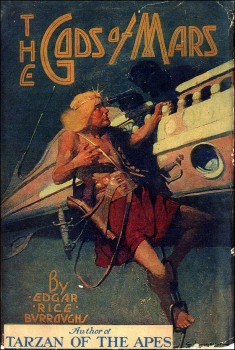

Shadow Prowler The year 2012 C.E. is the centenary of the Reader Revolution. Two novels published in pulp magazines that year, A Princess of Mars and Tarzan of the Apes, re-shaped popular fiction, helped change the United States into a nation of readers, and created the professional fiction writer. One man wrote both books: Edgar Rice Burroughs.

The year 2012 C.E. is the centenary of the Reader Revolution. Two novels published in pulp magazines that year, A Princess of Mars and Tarzan of the Apes, re-shaped popular fiction, helped change the United States into a nation of readers, and created the professional fiction writer. One man wrote both books: Edgar Rice Burroughs.