Leigh Brackett, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Appendix N: Advanced Readings in D&D

And so we come to the end of our extended journey through Gygax’s Appendix N, at the hands of our intrepid guides Tim Callahan and Mordicai Knode at Tor.com.

And so we come to the end of our extended journey through Gygax’s Appendix N, at the hands of our intrepid guides Tim Callahan and Mordicai Knode at Tor.com.

We haven’t always agreed with the opinions of Messieurs Callahan and Knode. But that’s okay. More than okay, really… what’s the point of following along with a literary survey if we don’t get to pound the table occasionally and shout “You lunkheads!” Really, the primary pleasure we old-timers get these days is disagreeing with self-proclaimed experts. Loudly, and at length.

But overall I think Callahan and Knode, the Lewis and Clark of Appendix N, have done a fine job. They’ve surveyed every entry in Gary Gygax’s original list of authors who influenced Dungeons and Dragons, just as they promised when they set out nine months ago. Along the way, they’ve shared their opinions — sometimes as informed experts, sometimes as newbies coming to the work of the masters for the first time.

And at every stop, they’ve been honest with us on whether or not the books spoke to them as modern readers. I don’t think we can ask for anything more than that.

I’m going to miss following along with Tim and Mordicai. Whether I agreed with them or not — nodding along with “Yup, yer darn tootin’,” or banging my head on the table and cursing every reader born after 1990 — they were always entertaining, enlightening, and frequently very funny.

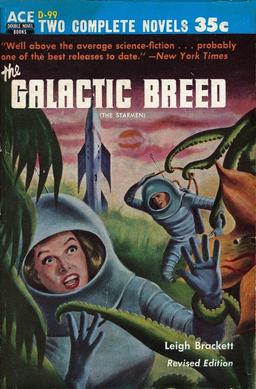

But we still have two last articles to examine: Mordicai’s appreciation of the grand old lady of science fantasy, Leigh Brackett, and Mordicai and Tim’s wrap-up of the entire series, their salute to J.R.R. Tolkien. Let’s see if these last two pieces bring more nodding, or table-banging.