The Astounding Life of John W. Campbell

|

|

Every now and then, amid your fevered cries for net neutrality, free soil and free silver, the restoration of the house of Stuart, more episodes of Firefly, or whatever other hopeless cause gets your blood racing and your family members fleeing (they recognize a wind-up to a full fledged rant when they hear one), against all odds the universe actually hears, takes note, and gives you precisely what you’ve asked for — not often, dammit, but sometimes.

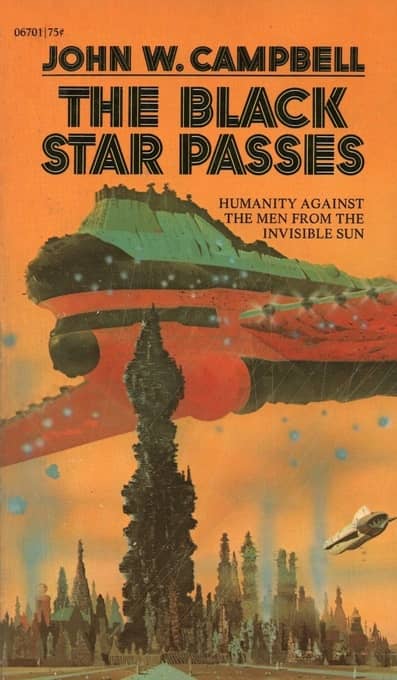

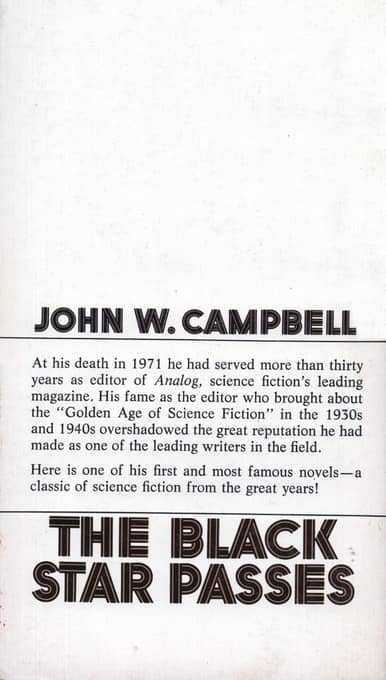

Thus it was that after decades of buttonholing strangers and lecturing them on the nation’s desperate need for a biography of John W. Campbell, the pioneering science fiction writer and influential editor of Astounding Science Fiction (later Analog) from 1937 until his death in 1971, a couple of months ago I discovered that just such a book had finally been written. (Where did I find this out? I saw it mentioned on some fantasy web site or other… hold on… I’ll think of the name in a minute…)

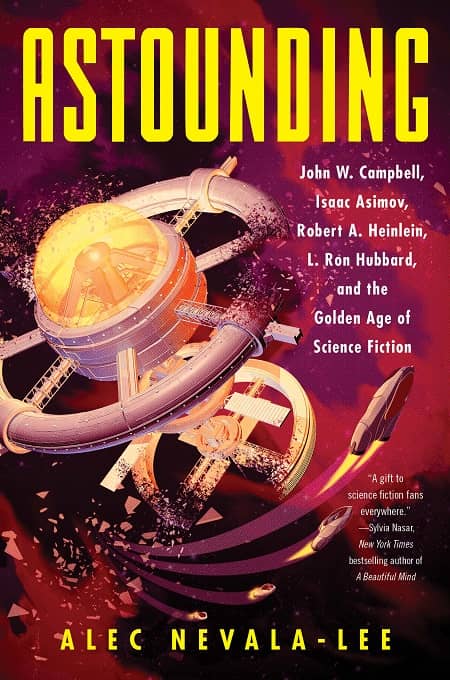

I Immediately put Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction by Alec Nevala-Lee at the top of my Christmas list, and I have just finished devouring it, blurbs, book jacket, binding glue, and all. Give me a second to belch, and I’ll tell you what I thought.