Modular: Picking Pathfinder

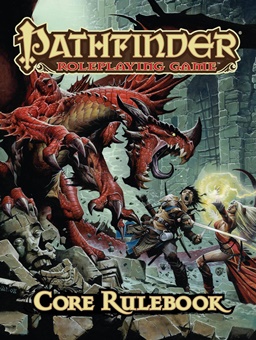

I’m cur rently running a Swords & Wizardry (S&W) campaign for a few friends. I wrote here about why I chose S&W instead of my preferred system, Pathfinder. In fact, that post served as the genesis for this Black Gate feature, Modular. But now, I’m going to look at some of the strengths of Pathfinder and why, when this S&W campaign is done, I’m going to transition the group to a Pathfinder adventure.

rently running a Swords & Wizardry (S&W) campaign for a few friends. I wrote here about why I chose S&W instead of my preferred system, Pathfinder. In fact, that post served as the genesis for this Black Gate feature, Modular. But now, I’m going to look at some of the strengths of Pathfinder and why, when this S&W campaign is done, I’m going to transition the group to a Pathfinder adventure.

So, though I had both played and run Pathfinder, I chose S&W for reasons I talked about in that prior post. I wanted a more story-driven, less mechanics-based system. Also, because two-thirds of the party was new to pen and paper RPGing, I wanted something lighter in the rules department. And there’s no comparison between the two in that regard. The S&W Core Rules comes in at just over 140 pages. The Pathfinder Core Rulebook is almost 600!

Now, I explained in that first post that while I was still reading RPG products, I had stopped playing during 3rd Edition Dungeons & Dragons (D&D): there simply hadn’t been time for it.

But I wanted to get back into playing, and the choice seemed to be between Pathfinder and the newly released 4th Edition. Now, I had only ever played D&D, going back to 1st Edition. I mean, it was synonymous with role playing games and 4th Edition was the natural choice. But as I researched both systems, Pathfinder clearly seemed to be the way to go.