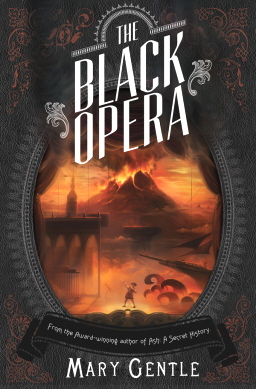

New Treasures: The Black Opera by Mary Gentle

I don’t know if British fantasy author Mary Gentle is all that well known here in the US. But in my native Canada — and especially among the fantasy fans I circulated among in Ottawa — she is highly respected indeed.

I don’t know if British fantasy author Mary Gentle is all that well known here in the US. But in my native Canada — and especially among the fantasy fans I circulated among in Ottawa — she is highly respected indeed.

Her first novel was Hawk in Silver, published in 1977 when she was only eighteen. But it was her two linked science fiction novels Golden Witchbreed (1983) and Ancient Light (1987) that really put her in the map. Her first major fantasy novel was Rats and Gargoyles (1990), the first volume of the White Crow sequence; perhaps her most acclaimed recent work has been Ash: A Secret History (2000, published in four volumes in the US) and Ilario (2007).

She’s also well known for Grunts! (1992), an action-packed send-up of epic fantasy, which follows Orc Captain Ashnak and his war-band as they take arms against the insufferable forces of Light — including murderous halflings and racist elves — who slaughter his orc brothers by the thousands in their path to inevitable victory.

Her newest novel is The Black Opera, and it has all the hallmarks of Gentle’s original and thought-provoking fantasy:

Naples, the 19th Century. In the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, holy music has power. Under the auspices of the Church, the Sung Mass can bring about actual miracles like healing the sick or raising the dead. But some believe that the musicodramma of grand opera can also work magic by channeling powerful emotions into something sublime. Now the Prince’s Men, a secret society, hope to stage their own black opera to empower the Devil himself – and change Creation for the better! Conrad Scalese is a struggling librettist whose latest opera has landed him in trouble with the Holy Office of the Inquisition. Rescued by King Ferdinand II, Conrad finds himself recruited to write and stage a counter opera that will, hopefully, cancel out the apocalyptic threat of the black opera, provided the Prince’s Men, and their spies and saboteurs, don’t get to him first. And he only has six weeks to do it…

The Black Opera was published in May by Night Shade Press. It is 515 pages (including a one-page appendix, “Rude Italian for Beginners,”) and is available for $15.99 in trade paperback and $9.99 in various digital formats.