Fantasia 2020, Part XXXIX: Lapsis

Science fiction has strong historical links to the adventure genre, but ideas-oriented science fiction tends to move away from adventure. Adventure fiction typically focusses on individual protagonists doing world-altering things, and a science fiction backdrop makes for a fictional world susceptible to alteration. But much actual social change is driven by organisations and groups, and science fiction that wants to talk about ideas usually acknowledges that. At the extreme you get something like Asimov’s early Foundation stories: tales in which the inevitable working-out of sociological forces are at the centre of the story, not the actions of a single hero. It’s not impossible to balance a quest-story about a single protagonist with a realistic portrayal of a world defined by its social structures, but tales that pull off both aspects are worth noting.

Science fiction has strong historical links to the adventure genre, but ideas-oriented science fiction tends to move away from adventure. Adventure fiction typically focusses on individual protagonists doing world-altering things, and a science fiction backdrop makes for a fictional world susceptible to alteration. But much actual social change is driven by organisations and groups, and science fiction that wants to talk about ideas usually acknowledges that. At the extreme you get something like Asimov’s early Foundation stories: tales in which the inevitable working-out of sociological forces are at the centre of the story, not the actions of a single hero. It’s not impossible to balance a quest-story about a single protagonist with a realistic portrayal of a world defined by its social structures, but tales that pull off both aspects are worth noting.

Which brings me to writer-director Noah Hutton’s Lapsis, an excellent near-future science fiction film that does both things very well indeed. Not too long from now, the quantum internet connects the world. To make the quantum computing systems work, cablers need to connect long cables between large cube-shaped nodes. These nodes are built in wilderness areas, so cablers have to walk through the woods trailing a wire behind them. They get paid well for this, in gig-economy fashion: if you have a cabler medallion, you log into an account, select a path, and take your cable along the path. You have to hurry to get the cable laid before a bot passes you by and steals the route, though, for if that happens you don’t get the points that’ll give you your payout.

Ray (Dean Imperial) is a blue-collar deliveryman whose boss gets busted, necessitating a search for a new job. Ray’s got a brother, Jaimie (Babe Howard) who he loves dearly but who suffers from a terrible fatigue-related condition, and to pay for an experimental treatment Ray strikes a deal with an underworld connection to get an under-the-counter cabling medallion. Cabling’s harder work than Ray expected, but things get really weird when he logs in to the account associated with the medallion — and finds a hoard of points already there. And finds other cablers grow hostile at the mention of his account’s name. Ray’s got to solve the mystery of the account, support his brother’s treatment, stay out of jail, and succeed at laying cable through a forest filled with people who seem to get stranger the farther he goes.

This is an excellent set-up, and Hutton explores it with profound intelligence and creativity. He has a background in documentary film, including two films about the oil industry and an ongoing project about an attempt to build a computerised simulation of a human brain; this perhaps helped him develop a future world that feels so deeply real. Lapsis is a thorough and solid extrapolation of the modern world, not just in terms of the macro scale of the class system and the gig economy, but in smaller stuff like the cheerful interface for the cablers’ accounts. Or the way the sharing economy has expanded to the point people rent storage space in their garage.

Yesterday I wrote about

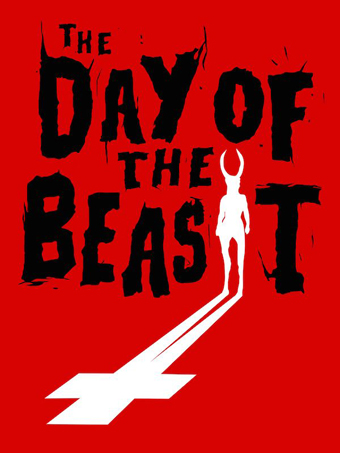

Yesterday I wrote about  Macbeth is one of the earliest true horror stories, in the sense of a story whose main aim is to play with the emotion of fear, and there’s a notable comic-relief scene with a gatekeeper right after the first gruesome murder. That scene became the subject of a famous essay by Thomas de Quincey arguing (roughly) that the horror’s made greater by contrast. So from the point where horror first began to emerge as a genre, storytellers have been conscious of the effect that comes from balancing horror with the everyday, and even with the comedic.

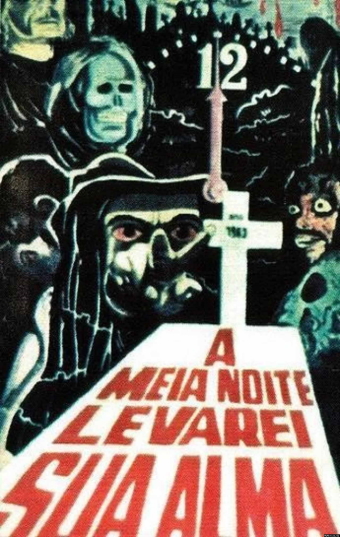

Macbeth is one of the earliest true horror stories, in the sense of a story whose main aim is to play with the emotion of fear, and there’s a notable comic-relief scene with a gatekeeper right after the first gruesome murder. That scene became the subject of a famous essay by Thomas de Quincey arguing (roughly) that the horror’s made greater by contrast. So from the point where horror first began to emerge as a genre, storytellers have been conscious of the effect that comes from balancing horror with the everyday, and even with the comedic. Brazilian director José Mojica Marins died earlier this year at the age of 83. He made low-budget films across a number of genres, with his horror work best known. His character Coffin Joe (Zé do Caixão), introduced in the 1963 film At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul (A Meia Noite eu Levarei sua Alma) is a kind of national ghoul of Brazil. Fantasia decided to honour Marins by making three of his films available on-demand through the festival, and scheduling a talk about Marins with his friend Dennison Ramalho on the last day of the festival;

Brazilian director José Mojica Marins died earlier this year at the age of 83. He made low-budget films across a number of genres, with his horror work best known. His character Coffin Joe (Zé do Caixão), introduced in the 1963 film At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul (A Meia Noite eu Levarei sua Alma) is a kind of national ghoul of Brazil. Fantasia decided to honour Marins by making three of his films available on-demand through the festival, and scheduling a talk about Marins with his friend Dennison Ramalho on the last day of the festival;  Film noir’s usually thought of as an urban genre. Its standard setting is the mean streets down which a man must go who is not himself mean. But a city’s not necessary; the Criterion Channel recently hosted a collection of Western Noir, films like Rancho Notorious and The Walking Hills. The ingredients for noir — violence, criminality, a morally bleak world — can be brought together anywhere.

Film noir’s usually thought of as an urban genre. Its standard setting is the mean streets down which a man must go who is not himself mean. But a city’s not necessary; the Criterion Channel recently hosted a collection of Western Noir, films like Rancho Notorious and The Walking Hills. The ingredients for noir — violence, criminality, a morally bleak world — can be brought together anywhere. The Western’s an American genre in origin, but Europeans from Sergio Leone to Charlier and Moebius have done interesting work in the form. Usually, though, European Westerns follow American heroes. That is, the European creators are still telling American stories. Savage State (L’État Sauvage), a Western from French writer/director David Perrault, does something different, following a French family trying to get out of the American South during the Civil War. It’s a nice idea. Unfortunately, the execution’s lacking.

The Western’s an American genre in origin, but Europeans from Sergio Leone to Charlier and Moebius have done interesting work in the form. Usually, though, European Westerns follow American heroes. That is, the European creators are still telling American stories. Savage State (L’État Sauvage), a Western from French writer/director David Perrault, does something different, following a French family trying to get out of the American South during the Civil War. It’s a nice idea. Unfortunately, the execution’s lacking. Every story’s got a genre, even if the story’s the sole example of its genre, so by extension a lot of stories use genre conventions and trust that the audience will accept them even if they’re unlikely or unbelievable. Often the audience does, especially when the conventions are so common they don’t register as conventions. But a story usually works better the more it can justify its conventions. Especially when the justification, and the convention, work with the story’s theme.

Every story’s got a genre, even if the story’s the sole example of its genre, so by extension a lot of stories use genre conventions and trust that the audience will accept them even if they’re unlikely or unbelievable. Often the audience does, especially when the conventions are so common they don’t register as conventions. But a story usually works better the more it can justify its conventions. Especially when the justification, and the convention, work with the story’s theme. One of the crucial differences between the way a storyteller approaches the tale they’re telling and the way the audience experiences that tale is that the storyteller typically knows the ending in advance. If they don’t start with the ending and work to that, they’ve usually still worked out multiple drafts of the story, if only in their head. The audience, on the other hand, at least on their first experience of a story doesn’t get to the end until they’ve gone through the whole of the work leading there. Even if they’ve heard something of the ending, or guess at it, the body of the work is necessarily the main part of the experience. If you just get the ending, you haven’t really gotten the whole story.

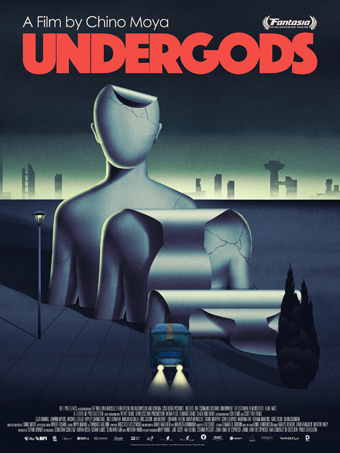

One of the crucial differences between the way a storyteller approaches the tale they’re telling and the way the audience experiences that tale is that the storyteller typically knows the ending in advance. If they don’t start with the ending and work to that, they’ve usually still worked out multiple drafts of the story, if only in their head. The audience, on the other hand, at least on their first experience of a story doesn’t get to the end until they’ve gone through the whole of the work leading there. Even if they’ve heard something of the ending, or guess at it, the body of the work is necessarily the main part of the experience. If you just get the ending, you haven’t really gotten the whole story. There is a certain tone I find in some works of science fiction, almost all from Europe, a ‘literary’ approach that uses science-fictional imagery with self-conscious irony in a way that at least approaches allegory and often satire. In prose I associate this approach with Lem and indeed Kafka; in film, with Tarkovsky’s science-fiction (adapting Lem and the Strugatskys) and Alphaville and On The Silver Globe. The focus in these works is less on world-building than on symbolism, and often on a narrative structure that layers stories within stories and plays with chronology. At their best, these tales emphasise the purely fantastic essence at the heart of science fiction: a type of wonder that uses a modern vocabulary.

There is a certain tone I find in some works of science fiction, almost all from Europe, a ‘literary’ approach that uses science-fictional imagery with self-conscious irony in a way that at least approaches allegory and often satire. In prose I associate this approach with Lem and indeed Kafka; in film, with Tarkovsky’s science-fiction (adapting Lem and the Strugatskys) and Alphaville and On The Silver Globe. The focus in these works is less on world-building than on symbolism, and often on a narrative structure that layers stories within stories and plays with chronology. At their best, these tales emphasise the purely fantastic essence at the heart of science fiction: a type of wonder that uses a modern vocabulary.