The Golden Age

There’s a famous epigram mistakenly attributed to a number of different people – as famous epigrams so often are – that states that “the golden age of science fiction is twelve.” Some quick research into the matter reveals that its actual author was Peter Graham, an editor of fanzines in the late 1950s and early ’60s. My research also revealed that the original quote stated the golden age of science to be thirteen.

There’s a famous epigram mistakenly attributed to a number of different people – as famous epigrams so often are – that states that “the golden age of science fiction is twelve.” Some quick research into the matter reveals that its actual author was Peter Graham, an editor of fanzines in the late 1950s and early ’60s. My research also revealed that the original quote stated the golden age of science to be thirteen.

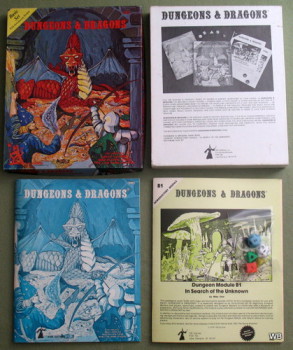

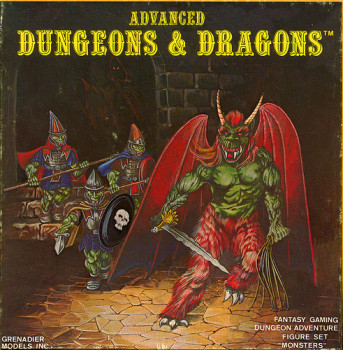

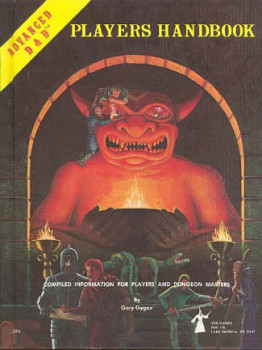

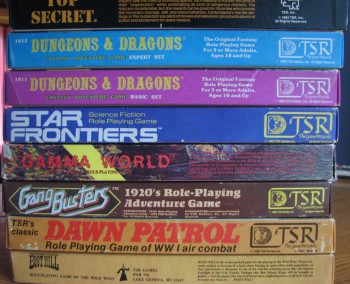

I turned thirteen in the Fall of 1982, three years after I first discovered Dungeons & Dragons. By that time, I was hopelessly in the thrall not just of D&D, but of a wide variety of roleplaying games. RPGs played a very important role in my young life, complementing many of my earlier interests and hobbies (like mythology, science fiction, and fantasy) and fostering many news ones (such as history, foreign languages, and philosophy). It is no exaggeration to say that I’d be a completely different man today if it weren’t for these games.

Consequently, I tend to look back on that time as a golden age, a time when the hobby of roleplaying was just right for a kid like me. I was reminded of this recently when I returned to visit my mother at my childhood home. Though I haven’t lived in that house on a permanent basis since I first went away to college in 1987, it still holds a great many things belonging to me that I simply hadn’t had the time to take with me as I traveled up and down the East Coast of North America. This year, I vowed that, during my visit, I’d do a proper inventory of what I’d left behind so that I could get rid of the stuff I didn’t want and once again take possession of at least some of the rest.

What I found was a time capsule of the inner life of my thirteen year-old self.