A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Patrick Maynard’s ‘Shades of Yellow’

Because I find it’s easier to get somebody else to do all the heavy lifting, I secured another guest poster for this week! Fellow Black Gater William Patrick Maynard knows more about Fu Manchu and the Yellow Peril genre than anybody else I know. And if you see his credentials at the end of the post, you’ll understand why! Today, he takes a pulpy look at the ‘menace from the Far East’ topic. Read on!

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” — Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

Context is a challenge in politically correct times that seek to view the past through the myopic lenses of an eternal present. Over 130 years ago, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle created an archetype in fiction with his consulting detective Sherlock Holmes. While Holmes lives on at least in name and reputation, most of his antecedents, contemporaries, and successors in the fantastic fiction of the Victorian and Edwardian eras are rapidly fading into obscurity.

Context is a challenge in politically correct times that seek to view the past through the myopic lenses of an eternal present. Over 130 years ago, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle created an archetype in fiction with his consulting detective Sherlock Holmes. While Holmes lives on at least in name and reputation, most of his antecedents, contemporaries, and successors in the fantastic fiction of the Victorian and Edwardian eras are rapidly fading into obscurity.

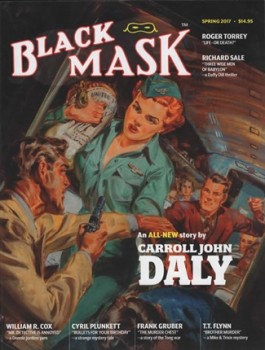

While forgotten by the public at large, the traits and exploits of many of these same characters have been disseminated into today’s pop culture icons (James Bond, Star Wars, Indiana Jones, and the glut of superheroes that continue to dominate movie screens). What remains of the past is largely through the efforts of pulp specialty publishers and public domain reprint specialists who keep these classic works in print for a niche market that still reads works from a different, simpler, though not always better, world.

Much of this fantastic fiction sprung directly from colonial viewpoints of the British Empire. Among the xenophobic byproducts of colonialism in popular culture was the Yellow Peril, the paranoid delusion that Chinese immigrants were plotting to conquer the West. There was certainly crime in Chinatown: there is always crime among the economically underprivileged, but what made the Yellow Peril thrive as a sub-genre of the thriller was the creation of a brilliant, amoral Chinese criminal mastermind in the same fashion as Conan Doyle’s Professor Moriarty and Guy Boothby’s Dr. Nikola.

Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu became the personification of the Yellow Peril. Without the character’s introduction, the sub-genre would never have prevailed. Fu Manchu took the reading public by storm just before the outbreak of the First World War and remained a bestselling franchise up to the Cold War. Rohmer’s insidious fiend was everywhere: magazines (slicks, not pulps), books, newspaper strips, comic books, radio series, films, the theater, and eventually television.

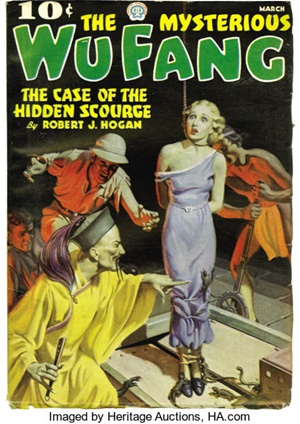

Holmes and Fu Manchu were certainly among the most influential characters in the first half of the last century. Arthur B. Reeve’s American variation on Holmes, the scientific detective Craig Kennedy was likewise pitted against a variation on Fu Manchu, the diabolical Wu Fang in The Exploits of Elaine (1914), The Romance of Elaine (1915), and The Triumph of Elaine (1915). The Elaine triptych were inspired by the phenomenal success of the 1914 serial, The Perils of Pauline.