Beau Geste: Myth vs. Reality

On my last trip to Tangier I purchased a 1925 edition of Beau Geste, one of those classic novels that I’ve always intended on reading but never had. It’s a swashbuckling tale of three brothers who join the French Foreign Legion a few years before the start of the First World War.

On my last trip to Tangier I purchased a 1925 edition of Beau Geste, one of those classic novels that I’ve always intended on reading but never had. It’s a swashbuckling tale of three brothers who join the French Foreign Legion a few years before the start of the First World War.

The novel opens with a mystery. Mild spoilers follow. A French officer in the Legion leads his troops to an isolated fort, responding to a call for help. Once there, he finds all the legionnaires dead inside, apparently shot by the warlike Tuareg. The commanding officer, however, has a French bayonet sticking out of his chest and the private beside him, although shot, has been carefully laid out with his hands across his chest. The private’s hat rests nearby, torn open. In the hands of the dead officer is a mysterious letter in English that contains a confession. . .

From that tantalizing beginning we cut to England, where three rich brothers have to flee home and end up in the French Foreign Legion. Add a cruel officer, hordes of Tuaregs, and some boon companions and you have the recipe for adventure. Author P.C. Wren writes in a breezy, wry style halfway between pulp pulse pounders and more highbrow literature. The style never feels dated although Wren’s worldview certainly does. There’s a definite hierarchy in this book, with the aristocratic Englishmen firmly at the top, the various Europeans and Americans they meet ranged further down depending on their social class, and the Arabs and Tuaregs right at the bottom. Women hardly figure in this book at all which, considering how agonizingly maudlin the one love scene comes off, is probably for the best.

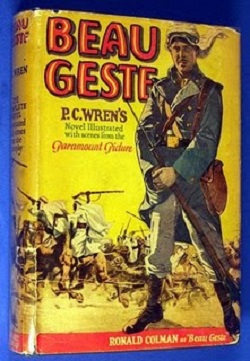

Doesn’t this look fun?

Wren’s novel was only one of a body of literature about the French Foreign Legion, but it more than any other single work gave the Legion its romantic glamor. The truth, of course, was a wee bit different. So after thoroughly enjoying this dated but fun novel, I read Douglas Porch’s The Conquest of the Sahara, considered one of the classic works on France’s colonial adventures in North Africa. For another, read my review of Lords of the Atlas.

The Conquest of the Sahara covers France’s colonial adventure from the early nineteenth century foothold in Tripoli through the next century as it took over the Sahara as far south as Timbuktu and Lake Chad. Porch shows how much of this wasn’t actually a policy of colonization planned in Paris, but rather one instigated by officers at the scene. The government in Paris was divided between liberals who saw no real need for expansion into North Africa, and a conservative pro-colonization party that wanted land no matter what the cost. Officers stuck in remote posts in the desert longed for glory, knowing they were considered the dregs of an army that was preoccupied with guarding the border with Germany. In order to compensate for this and gain some medals and promotions, they often overreacted to minor incidents by launching small-scale invasions.

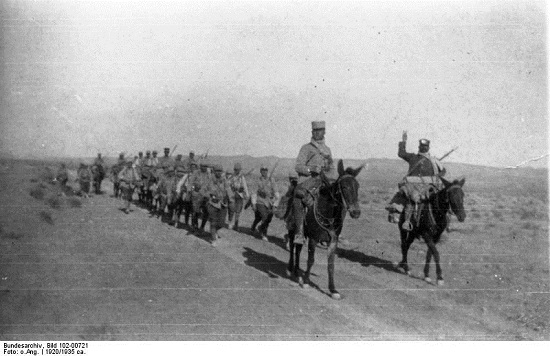

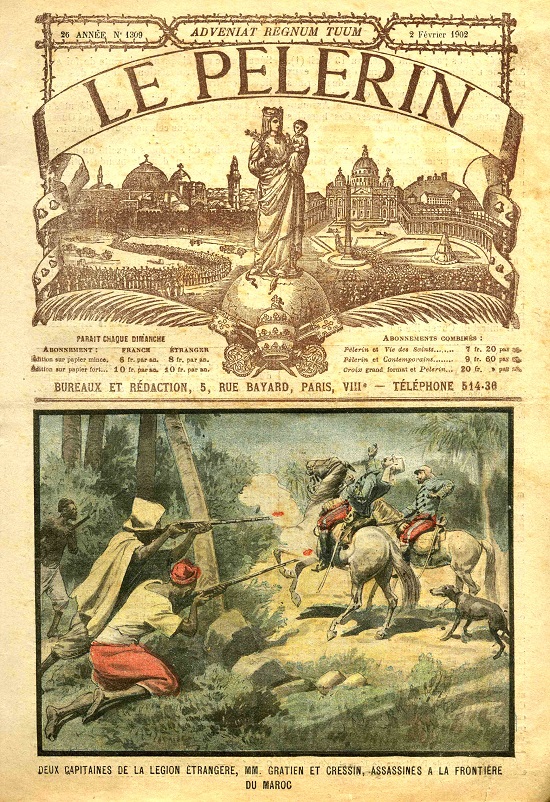

Even the popular press couldn’t hide the dangers of colonial service

Once these troops had taken a region, the government in Paris would be in a bind. It couldn’t abandon conquered territory without losing face, and thus after a bit of griping usually incorporated the new land into France’s overseas possessions. Thus France’s colonial conquests happened in fits and starts.

That conquest is not a pretty picture. Being poorly planned and undermanned, the various expeditions had to live off the land. The land, however, could barely support its small native population, let alone a few hundred newcomers and their camels. Villages would be stripped bare of food, exhausted mounts would be replaced with local requisitions, and anything else of value taken. Porch points out that in the desert cultures, camels were generally a family’s most valuable possession, being both a source of milk and a means of transport. When these were taken away without compensation, local families were left destitute.

They suffered even more when the French created an outpost at their oasis. The oases were watered by small traditional wells or foggaras, ingenious underground tunnels that channelled the water to small plots of farmland. These didn’t bring up enough water for the French garrisons and their thirsty mounts, so the French sank artesian wells. These wells managed to simultaneously dry out and flood the oases by lowering the water table to such an extent that plants wouldn’t grow while creating a stagnant lake that bred disease.

The opening of a foggara onto a plot of farmland in Libya

Then there were the officers themselves, ranging from expert to blundering to simply mad. The worst surely was Captain Paul Voulet, who led the Central African Mission in 1898, marching out of Senegal to conquer the Lake Chad. He gleefully burned villages as he passed through, forcing the men to be porters and killing the women and children if the men resisted, and sometimes even if they did not. His brutality shocked even the French colonial officials, and they sent an expedition after him to relieve him of command. This he ambushed, killing its officer and several men. He then declared he would set himself up as a black chieftain, but his own men knocked him off shortly thereafter.

What’s refreshing about Porch’s book is that it examines the cultures and power structures that were already in place before the French arrived. Far from being passive areas waiting to be conquered, the Sahara had a complex and shifting set of allegiances between various ethnic groups and social castes. The more intelligent French officers tried to balance these forces in order to make the transition from independent regions into colonies go as smoothly as possible, but more often than not orders from above destroyed their efforts. Porch’s book lives up to the title of one of its chapters by showing “The Dark Side of Beau Geste.”

The undermanned French garrisons often converted existing buildings into

forts. Ksar Aghlid may have been one of the two buildings that played a part in the

siege of Timimoune, when the Tuareg made a rare attack on two fortified buildings

by sneaking into them under cover of darkness. I can’t be for sure this is one

of them unless Black Gate sends me to southern Algeria. (hint hint)

I enjoyed reading a novel and a history book on the same subject and I think I’ll repeat the experience. Can anyone suggest any suitable pairings?

All images courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Sean McLachlan is the author of the historical fantasy novel A Fine Likeness, set in Civil War Missouri, and several other titles, including his post-apocalyptic series Toxic World that starts with the novel Radio Hope. His historical fantasy novella The Quintessence of Absence, was published by Black Gate. Find out more about him on his blog and Amazon author’s page.

I’ve not read the novel, but I can highly recommend the 1939 movie with Gary Cooper, Ray Milland, and Robert Preston as the Geste brothers and Brian Donlevy as Sergeant Markoff. Donlevy is so good he steals the movie; he elevates evil to a stature that practically dwarfs the tale’s nominal heroes.

And for a new pairing, How about The Siege of Krishnapur by J.G. Farrell. It’s about the Indian Mutiny and it’s the finest historical novel I’ve ever read; it’s perfectly balanced between acknowledging the folly and futility of British imperialism and giving the imperialists themselves their just due for their courage and resourcefulness. You could follow it up with Christopher Hibbert’s The Great Mutiny: India 1857, an excellent popular history of the catastrophe.

Captain Voulet puts me in mind of the notorious French mercenary Bob Denard. I remember reading the New York Times article when he took over the Comoros Islands as his own personal fiefdom in 1989. It was awful for the Comorian people, but the situation was so weird it was hard not to laugh at some of the details. When the French government was finally embarrassed enough to remove him from the presidential palace, they did it by threatening to seize a used car dealership he owned in Lyon. Yes, he’d taken over a country so poor that one used car dealership was worth more to him. It took a little Googling tonight for me to remember his name right, so I got to check out what else he’d been up to. What a bizarre life he lived. My favorite sentence from his Wikipedia entry:

In January 1968 he invaded Katanga with a force of a hundred men on bicycles in an attempt to create a diversion for a breakout from Bukavu.

It sounds like something out of a GURPS campaign.

How about The Roman Remains of Southern France: A Guidebook by James Bronwich with Guy Gavriel Kay’s Ysabel. Or Nancy Goldstone’s Four Queens: The Provencal Sisters Who Ruled Europe with Kay’s A Song for Arbonne.

I read BEAU GESTE a long time ago, as a teen, and remember quite enjoying it. I knew even then, mind you, that its depiction of the French Foreign Legion was not precisely in line with history.

Much more recently I read one of a couple of sequels: BEAU SABREUR. I covered it at my blog, here: http://rrhorton.blogspot.com/2014/05/old-bestsellers-beau-sabreur-by-p-c-wren.html

And for an even less nuanced portrayal of the people of the Sahara, there’s always THE SHEIK, which I also reviewed, here: http://rrhorton.blogspot.com/2014/11/old-bestsellers-sheik-by-e-m-hull.html.

(Caution: THE SHEIK may be the rapiest novel of all time, and not in a good way at all!)

Im 66 years old now and first read “Beau Geste ” when I was 12 years of age after watching the film version with Gary Cooper , Ray Milland and Robert Preston . In my opinion and despite the genre of it being a romantic adventure novel set in early 20th century England and moving on to the zenith of the piece in the deserts of French Colonial North Africa , it is a book that every true patriotic blue blooded Englishman should read at least once in his lifetime albeit very outdated by modern day standards . Since that first ever reading of this book 54 years ago , every 3 or 4 years I will pick it up and re read those same pages of which Ive almost memorised over time . I find it a feel good factor read and no doubt will pick it up again soon .