Greco-Roman and Early Christian Ruins at Bahariya Oasis, Egypt

The guard at the Temple of Alexander showing off

some of the stray finds to me and my Bedouin driver

In my last post, I talked about the Egyptian tombs at Bahariya Oasis, some 340 km southwest of Cairo. The oasis was on the fringe of civilization in those days, but became more important during the Greco-Roman period because its well-watered soil didn’t flood like the Nile valley and thus was a good place to grow grapes to make wine, something the Greeks and Romans couldn’t live without.

The oasis became prosperous during Greek and Roman rule. It gained significance right from the start when Alexander the Great passed through here on the way to Siwa Oasis further to the west, where he had his famous meeting with the oracle of Amun at the sanctuary there, where he was proclaimed the son of the god and thus pharaoh. The temple honors his visit to the oasis and is the largest in the Western Desert, with a two-room sandstone chapel and a temple enclosure with at least 45 rooms and a surrounding wall.

I’ve always loved vintage travelogues. The world was bigger a hundred years ago, its cultures more distinct and isolated. Travel was hard and sometimes dangerous. Accounts of old journeys bring me back to a time when people could go to places like Africa and not be able to text home.

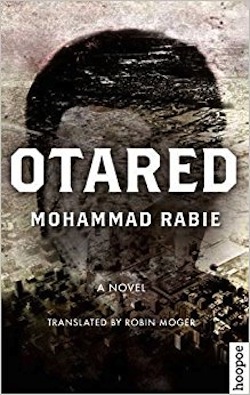

I’ve always loved vintage travelogues. The world was bigger a hundred years ago, its cultures more distinct and isolated. Travel was hard and sometimes dangerous. Accounts of old journeys bring me back to a time when people could go to places like Africa and not be able to text home. One pleasant stop on my recent trip to Cairo was the American University’s bookshop near Tahrir Square. It’s a treasure trove of books on Egyptology and Egyptian fiction in translation. Among the titles I picked up was the dystopian novel

One pleasant stop on my recent trip to Cairo was the American University’s bookshop near Tahrir Square. It’s a treasure trove of books on Egyptology and Egyptian fiction in translation. Among the titles I picked up was the dystopian novel

On my last trip to

On my last trip to