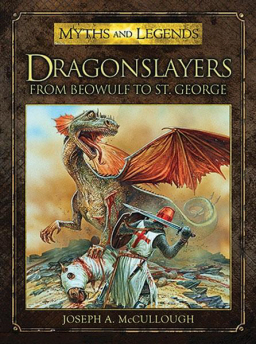

How to Slay a Dragon, Realistically

One of the draws of Heroic Fantasy is that it takes the archetypal, the magical — the magical realistic even! — and makes it immersively real by engaging with it in a practical, sweaty-browed, grimy handed way.

For example, a surrealist artist might paint a city inhabited by human wolves, but James Enge in Wolf Age plunges his hero into a realistically imagined civilization of werewolves and makes him fight to survive physically and morally.

That’s what the genre does. It says: Assume this crazy but cool thing was true; what would be the implications?

Now, dragons are about as crazy and cool and magical as beasts get. Suppose you had to kill one?

Don’t look to Greek Myth for tips! Yes, Heracles prunes the Hydra to death, but he’s a demigod. Jason slays the Colchian dragon, but only after Media cast Sleep on it. Faced by a dragon, a mythological hero uses supernatural cheat codes. Puny humans without magic or divine descent don’t get a look in — which is fine. The listener, or reader, is civilised, and dragons belong to another era.

You’ll have more luck with the tales crafted — evolved in the telling — for the descendants of the barbarians who took down the Roman Empire. These rough men were accustomed to resolving problems through the medium of muscle-powered violence. The dragon, like a post-Roman city, a Byzantine army, or the walls of Jerusalem, merely presented an interesting challenge and thus their response becomes interesting to us:

So how does a Dark Age warrior or Medieval knight imagine he might kill a dragon?

To my mind, if you’re a critic of any integrity, sooner or later the criticism you write will lead you to challenge your views of yourself as well as your views of the art you experience. That’s the nature of much truly effective art: it makes you look at yourself and think about yourself in new ways. If you’re trying to articulate your reaction and assessment of such a work, honesty will compel some self-examination as well. Powerful art requires an acknowledgement of one’s subjective response.

To my mind, if you’re a critic of any integrity, sooner or later the criticism you write will lead you to challenge your views of yourself as well as your views of the art you experience. That’s the nature of much truly effective art: it makes you look at yourself and think about yourself in new ways. If you’re trying to articulate your reaction and assessment of such a work, honesty will compel some self-examination as well. Powerful art requires an acknowledgement of one’s subjective response.

Saturday was my first really big day at Fantasia. On weekdays, the festival usually starts its screenings at 5 or 6, with the occasional matinée at 3. Weekend days kick off around noon, meaning many more movies are on offer. Which also incidentally increases the risk of losing track of the need for a meal. I ended up seeing five movies last Saturday, with a dinner break after the first three. So this post will cover those first three films and I’ll have another up shortly looking at the next two. (In general it seems like I’m going to have more Fantasia posts than I’d thought, as I try to keep up with the films I’ve watched.)

Saturday was my first really big day at Fantasia. On weekdays, the festival usually starts its screenings at 5 or 6, with the occasional matinée at 3. Weekend days kick off around noon, meaning many more movies are on offer. Which also incidentally increases the risk of losing track of the need for a meal. I ended up seeing five movies last Saturday, with a dinner break after the first three. So this post will cover those first three films and I’ll have another up shortly looking at the next two. (In general it seems like I’m going to have more Fantasia posts than I’d thought, as I try to keep up with the films I’ve watched.)