Fantasia Focus: The Zero Theorem, by Terry Gilliam

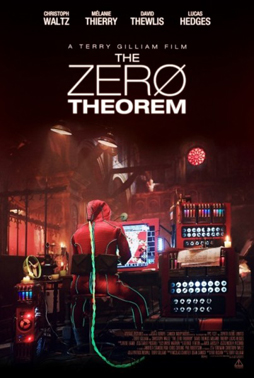

Before continuing my Fantasia diary with a look at the movies I saw last Sunday, I want to focus in on one specific film that struck me as an utterly brilliant piece of science-fiction satire. I think it divided the audience; I’ve heard and seen reactions from people who were left cold by it as well as from people who loved it as much as I did. Perhaps that’s not surprising. The movie is The Zero Theorem, directed by Terry Gilliam from a script by Pat Rushin, and it is as idiosyncratic and persistently individual as you’d expect from Gilliam.

Before continuing my Fantasia diary with a look at the movies I saw last Sunday, I want to focus in on one specific film that struck me as an utterly brilliant piece of science-fiction satire. I think it divided the audience; I’ve heard and seen reactions from people who were left cold by it as well as from people who loved it as much as I did. Perhaps that’s not surprising. The movie is The Zero Theorem, directed by Terry Gilliam from a script by Pat Rushin, and it is as idiosyncratic and persistently individual as you’d expect from Gilliam.

Qohen Leth (Christoph Waltz) is an eccentric solitary in a hyperconnected future. He works for a corporation, Mancom, plugging numbers together — which he does by manipulating blocks on a screen with a joystick, effectively playing video games. A chance encounter with Management (Matt Damon) allows him to work from home, a deserted church, trying to put together the zero theorem, a mathematical proof of the pointlessness of life — which Management believes can be leveraged to make money. Qohen’s pleased, since what he wants more than anything else in life is a phone call he believes will come out of the blue and grant him enlightenment, and now he can sit at home and wait for the phone to ring. But his solitude’s plagued by outsiders, including the seductive Bainsley (Mélanie Thierry), and Management’s son Bob (Lucas Hedges), an even sharper computer whiz than Qohen.

The Zero Theorem is visually startling, steampunk gone day-glo. It’s a perceptive, idiosyncratic take on the Wired World Of Today, here depicted as Brave New World gone berserk. In fact, Gilliam considers this movie part of his ‘Orwellian trilogy,’ along with Brazil and Twelve Monkeys, but it certainly feels more like Huxley. It depicts a world commercialised and infantilised, where ads for the Church of Batman the Redeemer float above the street. It’s a sharp criticism of easy escapism, but seems to question as well where contrasting meaning is to be found, whether religious transcendence is valid or whether belief is just another form of escape. The movie’s more interested in questions than answers, even questioning itself and its own metaphors on occasion. Days later, I’m still thinking about it, arguing with it, astounded by it.

To my mind, if you’re a critic of any integrity, sooner or later the criticism you write will lead you to challenge your views of yourself as well as your views of the art you experience. That’s the nature of much truly effective art: it makes you look at yourself and think about yourself in new ways. If you’re trying to articulate your reaction and assessment of such a work, honesty will compel some self-examination as well. Powerful art requires an acknowledgement of one’s subjective response.

To my mind, if you’re a critic of any integrity, sooner or later the criticism you write will lead you to challenge your views of yourself as well as your views of the art you experience. That’s the nature of much truly effective art: it makes you look at yourself and think about yourself in new ways. If you’re trying to articulate your reaction and assessment of such a work, honesty will compel some self-examination as well. Powerful art requires an acknowledgement of one’s subjective response.

Saturday was my first really big day at Fantasia. On weekdays, the festival usually starts its screenings at 5 or 6, with the occasional matinée at 3. Weekend days kick off around noon, meaning many more movies are on offer. Which also incidentally increases the risk of losing track of the need for a meal. I ended up seeing five movies last Saturday, with a dinner break after the first three. So this post will cover those first three films and I’ll have another up shortly looking at the next two. (In general it seems like I’m going to have more Fantasia posts than I’d thought, as I try to keep up with the films I’ve watched.)

Saturday was my first really big day at Fantasia. On weekdays, the festival usually starts its screenings at 5 or 6, with the occasional matinée at 3. Weekend days kick off around noon, meaning many more movies are on offer. Which also incidentally increases the risk of losing track of the need for a meal. I ended up seeing five movies last Saturday, with a dinner break after the first three. So this post will cover those first three films and I’ll have another up shortly looking at the next two. (In general it seems like I’m going to have more Fantasia posts than I’d thought, as I try to keep up with the films I’ve watched.)