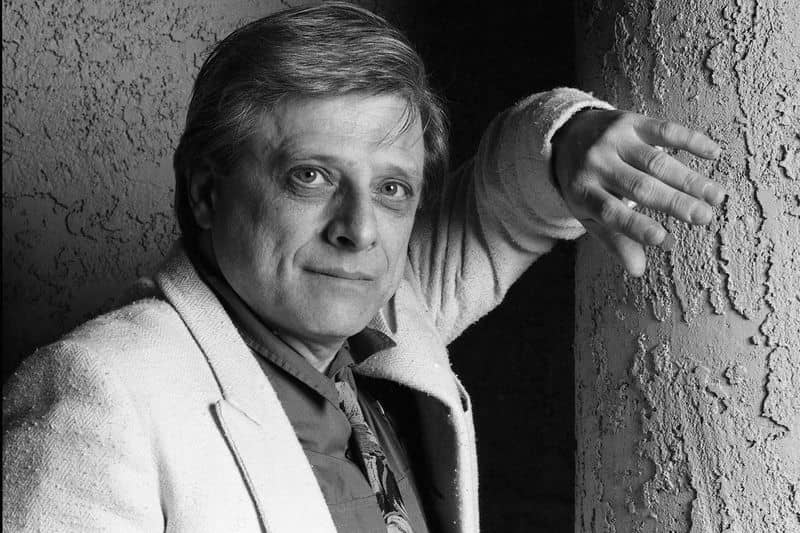

Harlan Ellison 1934-2018: Essential and Impossible

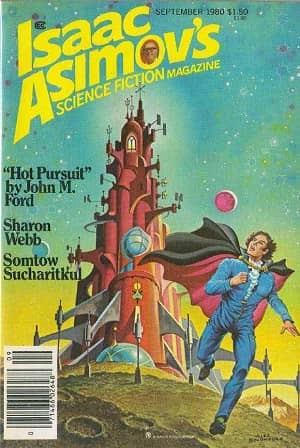

Did you feel that? That sudden drop in pressure, that slump, as if the world itself had let out a long-held breath? I’m sure it was registered on every spot on earth, from Cleveland to Calcutta, from Reykjavik to Tierra del Fuego. That was Harlan Ellison leaving the building. No man was ever less likely to die peacefully in his sleep at the ripe old age of eighty four, but that’s exactly what happened on the morning of June 28th, and the effect is tantamount to global nuclear disarmament. The immanent threat is over; finally, we can all relax a bit.

An authoritative assessment of Ellison’s tumultuous sixty year career can now begin and is far beyond the scope of this piece, even if I had the ability to do it — which I don’t. All that I can say is that the world has instantly become a less interesting, less vital place than it was when the human bomb that was Harlan Ellison was still ticking away. He was one of those rare people who can actually alter the atmosphere; in his presence, the air was sharper, the light brighter, the temperature higher, and everything seems a little dulled and diminished now that he’s gone.

The couple of times that I met him in person — in the mid 70’s, at the legendary Change of Hobbit bookstore in Los Angeles — the intensity and excitement radiated from him in waves. It was actually a bit frightening, like being too close to an enormous bonfire. It was immediately evident that this was a dangerous person; he would break boundaries in ways good and bad, because that was life to him, and he didn’t know any other way to exist. It’s amazing that he lived to be eighty four — by all rights he should have succumbed to stroke or homicide long ago.