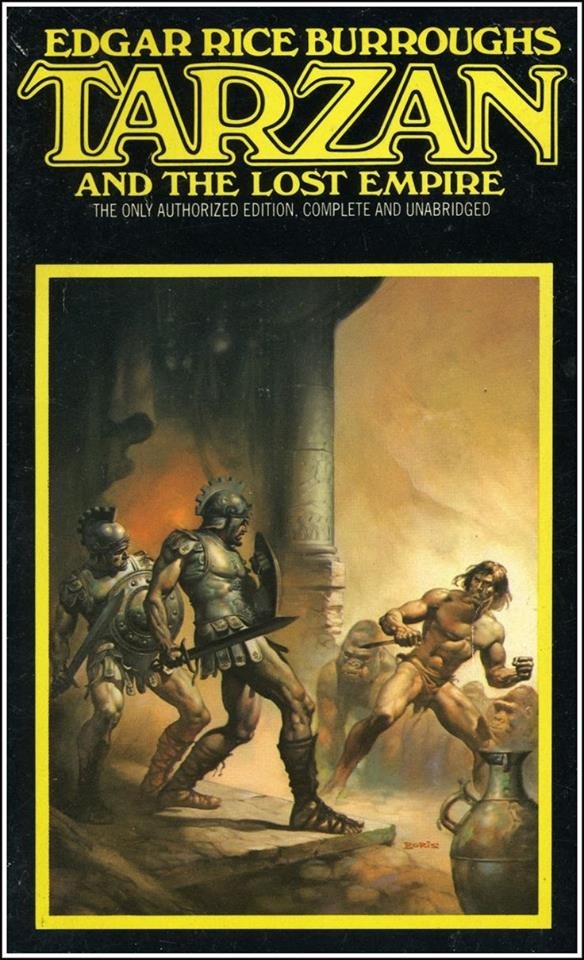

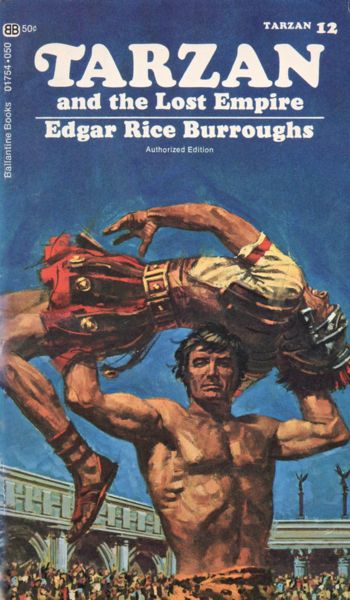

Tarzan Swing-By: Tarzan and the Lost Empire (1928–29)

Readers have asked me, but the answer is still no: I can’t tackle the entire Tarzan series the way I did Edgar Rice Burroughs’s other book series, Mars, Venus, and Pellucidar. There are twenty-four Tarzan books, not counting the juveniles, and I’d burn out long before the end if I tried to read them in sequence over a compressed time period.

But since I’m always glad to pick up a Tarzan volume here and there among my other Burroughs readings, I’ll negotiate. I’ll do an occasional Tarzan book “swing-by” to give spotlight time to ERB’s biggest contribution to popular culture. No particular order, just whatever Tarzan adventure grabs me at the moment.

So I’ll start with … let’s see … Book #12, Tarzan and the Lost Empire. Wherein the Lord of the Jungle finds yet another civilization lost in time in the heart of Africa: a remnant of the Roman Empire still living the ancient ways. Tarzan also gets a little monkey sidekick.

Tarzan and the Lost Empire falls into a period of the Tarzan novels that I think of as the “Filmation Era” because of how much the 1970s Filmation animated series Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle reflects it. After the tenth book, Tarzan and the Ant Men, Tarzan was distanced from the Greystoke legacy and his former supporting cast, and now has the companionship of both Nkima the monkey and Jad-bal-ja the golden lion. Jane vanished except for a single reappearance in Tarzan’s Quest (1936). The plots became standalone and repeated certain formulas, such as Tarzan discovering lost civilizations or facing a Tarzan imposter.

The writing quality of these books was still high in the late ‘20s and early ‘30s, and Burroughs hadn’t lost his skill at executing pulse-racing action set-pieces. But the plotting was often perfunctory as ERB became a bit fatigued with having to go back to the Tarzan well again and again. The story ideas and the prose popped, but the plots often meandered with overstuffed casts and too much incident that doesn’t go anywhere. Tarzan and the Lost Empire falls prey to these faults. But it also contains one of the most interesting hidden civilizations of the series and a setting that energized Burroughs.

Dueling Cities of the Lost Roman Empire

The book opens strong — Burroughs was fantastic at motivating his characters early and snaring readers from the first pages. Tarzan receives a visit from his friend, Dr. von Harben, who asks if the ape-man will locate his son Erich’s vanished expedition. The young von Harben was searching for the truth behind the legends of the Lost Tribe of the Wiramwazi Mountains, who are rumored to be bloodthirsty ghosts.

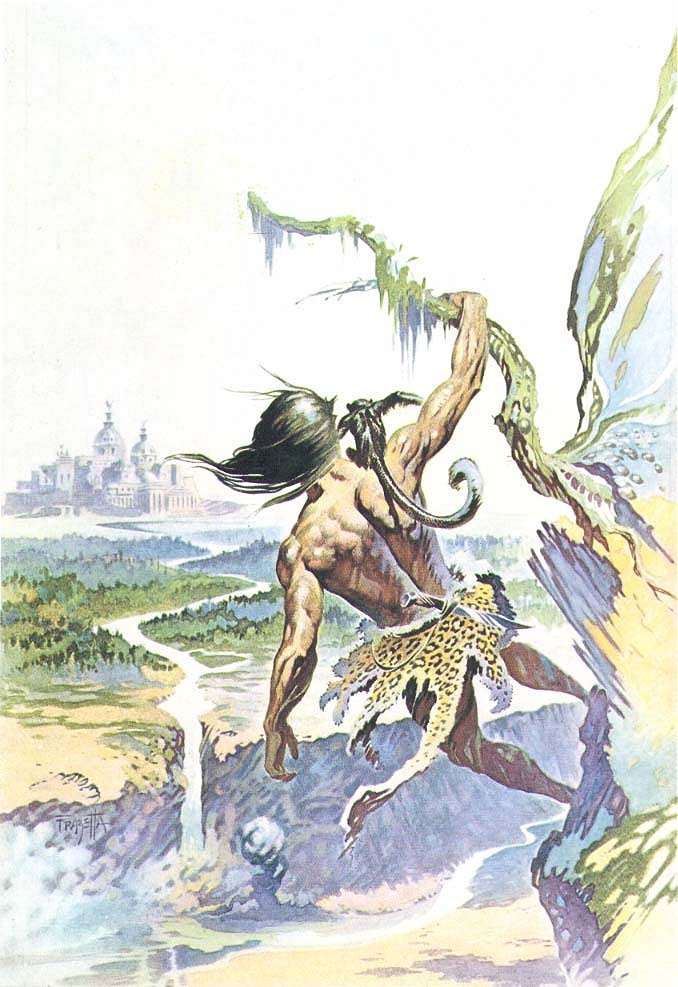

Tarzan sets out with his monkey (Manu) companion, Nkima, and the story switches into the standard Tarzan book structure of alternating chapters following different protagonists. Erich von Harben and Gabula, the last loyal member of his expedition, discover a secret valley that contains two warring cities inhabited by remnants of the Roman Empire: Castra Sanguinarius and Castrum Mare. Castra Sanguinarius was founded by Honus Hosta, a Roman centurion who fled into the interior of Africa to escape the wrath of Emperor Nerva eighteen hundred years ago. Castrum Mare splintered off as a separate settlement a century afterward, leading to opposed “Emperors of the East and West.” The cities trade goods between each other, but otherwise remain in a state of continual war, both with each other and the black Bagego tribe of the valley.

Tarzan sets out with his monkey (Manu) companion, Nkima, and the story switches into the standard Tarzan book structure of alternating chapters following different protagonists. Erich von Harben and Gabula, the last loyal member of his expedition, discover a secret valley that contains two warring cities inhabited by remnants of the Roman Empire: Castra Sanguinarius and Castrum Mare. Castra Sanguinarius was founded by Honus Hosta, a Roman centurion who fled into the interior of Africa to escape the wrath of Emperor Nerva eighteen hundred years ago. Castrum Mare splintered off as a separate settlement a century afterward, leading to opposed “Emperors of the East and West.” The cities trade goods between each other, but otherwise remain in a state of continual war, both with each other and the black Bagego tribe of the valley.

Erich von Harben is taken captive in Castrum Mare, while Tarzan ends up in the cells of Castra Sanguinarius. The narrative hops between the cities and the plotting and scheming boiling in both. But after Chapter Ten, von Harben and the situation in Castrum Mare drop out of the story almost completely. The next ten chapters are about Tarzan’s battles in the Colosseum of Castra Sanguinarius and the raising of a revolt against Emperor Sublatus. Von Harben is mentioned only twice during this time, just to remind readers that he’s still around.

Without question, the action with Tarzan in Castra Sanguinarius is the most exciting part of the book. The main arena battle, which hurtles across three thrilling chapters, is bloody good fun and has a classic Tarzan vs. Lion showdown. (I’m amazed that I never tire of reading about this pairing.) There is a fist-pumping badass Tarzan moment when the ape-man refuses to kill a defeated gladiator opponent. To obey Emperor Sublatus’s order that only one man is allowed to walk out of the arena from a duel, Tarzan picks up the gladiator and hurls him into the emperor’s loge. Although the massive final fight to overthrow the emperor is sometimes snarled reading — too many characters dashing around trying to tie up plotlines — the arrival of Muviro and the Waziri tribesmen as the cavalry is a great finale.

But this begs the question: why give attention to Castrum Mare and Erich von Harben in the first place if they’re going to vanish for nearly half the book? I can think of two reasons, both devices Edgar Rice Burroughs often relied on: the secondary hero character and dueling cities. In this case, ERB would’ve been better off demoting the supporting hero and collapsing the cities into one.

Burroughs often created secondary protagonists in the later Tarzan novels so he wouldn’t have to rely on Tarzan exclusively to move the story along. Erich von Harben starts out fine in this role, and his archaeological and historical background helps describe the lost Roman setting. But once Erich completes the job of finding out the history of the settlements in his research in Castrum Mare’s library, he checks out until almost the end of the novel.

There isn’t anything wrong with Erich as a character. The passages of him contemplating the survival of the Iron Age in the modern era and contrasting it to his archaeological knowledge are among the book’s best moments. But when Erich’s story stops dead for ten chapters, readers can no longer invest much in him or his thwarted romance storyline. It retroactively makes his earlier scenes feel too much like exposition for exposition’s sake, no matter how well written they are.

A pair of dueling cities was a Burroughs perennial. I recently explored this in Savage Pellucidar, and Burroughs had just used it in the previous Tarzan novel, Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle, where it was lost crusader states from the Middle Ages. Here it feels like a needless complication. Castrum Mare isn’t substantially different enough from Castra Sanguinarius to merit parallel storytelling. What happens in the two cities — an uprising against an unpopular emperor, lovers forced apart because of an arranged marriage to a shifty villain — is almost identical. So Burroughs eventually settled on the city Tarzan was in and stuck with it. Erich von Harben’s imprisonment is left to a second-hand report crammed into an exposition catch-up chapter among the prisoners in the Colosseum of Castra Sanguinarius.

A pair of dueling cities was a Burroughs perennial. I recently explored this in Savage Pellucidar, and Burroughs had just used it in the previous Tarzan novel, Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle, where it was lost crusader states from the Middle Ages. Here it feels like a needless complication. Castrum Mare isn’t substantially different enough from Castra Sanguinarius to merit parallel storytelling. What happens in the two cities — an uprising against an unpopular emperor, lovers forced apart because of an arranged marriage to a shifty villain — is almost identical. So Burroughs eventually settled on the city Tarzan was in and stuck with it. Erich von Harben’s imprisonment is left to a second-hand report crammed into an exposition catch-up chapter among the prisoners in the Colosseum of Castra Sanguinarius.

The last three chapters do return to Castrum Mare’s political upheaval and Erich’s romance plot with Favonia and his fight with her suitor, Fulvus Fupus. But it’s a rushed coda, since the story effectively ended when Tarzan and his companions overthrew the emperor of Castra Sanguinarius.

The overall feeling is that Burroughs got bored with Erich von Harben and Castrum Mare and didn’t know where to take them. Telescoping the setting into a single Roman city would have made more sense. It’s such an obvious choice that I’m surprised Burroughs didn’t decide to keep only the Castra Sanguinarius chapters and rewrite the book around them. There’s already an abundance of storylines and characters in this one city to fill up a complete novel. In fact, the often dense plotting might benefit from more space to stretch out. It wouldn’t require much effort to alter the story so Erich is a captive in Castra Sanguinarius who remains out of sight until Tarzan is imprisoned with him. Erich can then relay his knowledge of the settlement’s history to Tarzan and the readers.

Burroughs may have felt locked into a story type he liked. Or he was simply dashing through the writing, which was something that would start to plague his books through the 1930s.

Love Your Latin

So the plot is muddled and unbalanced. But Tarzan and the Lost Empire still succeeds thanks to its setting of an anachronistic patch of ancient Rome dropped into central Africa. Specifically, it succeeds thanks to Burroughs’s enthusiasm about the setting. It’s exciting to watch ERB have a grand time researching a subject that fascinated him and decorating a book with it.

When a student at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, Ed had to take rigorous classes in Latin and Greek. He wasn’t fond of this rigid classical training, although he enjoyed making Latin puns in the Mirror, a school literary magazine. As an adult author, Burroughs discovered a fascination with Ancient Rome and its language, and his playful use of words found a new outlet in toying with Latin. There’s a good lesson here for modern students about the vitality and usefulness of Latin — but I’m projecting my own love of the language. Nonetheless, Tarzan and the Lost Empire shows what you too can achieve if you stick to your Latin studies!

Burroughs cut loose with inventing new Roman names and Latin terms. The scum-villain character is named Fulvus Fupus. That’s great! ERB liked to sound out his character names to test them, and according to his son Jack, he thought “Fulvus Fupus” was hilarious to say. I agree: it’s a funny name and it fits this milksop whiner if a character, especially if pronounced in correct classical style as “FUHL-wuss FUP-uss.” I like the special Burroughsian glimmer to names like Appius Applosus, Honus Hasta, and Dion Splendidus. Many of the book’s Latin terms have no connection to actual Latin; they’re ERB experimenting with the idea of the language evolving as an isolate over eighteen hundred years — and also having a good time slinging syllables around.

Burroughs cut loose with inventing new Roman names and Latin terms. The scum-villain character is named Fulvus Fupus. That’s great! ERB liked to sound out his character names to test them, and according to his son Jack, he thought “Fulvus Fupus” was hilarious to say. I agree: it’s a funny name and it fits this milksop whiner if a character, especially if pronounced in correct classical style as “FUHL-wuss FUP-uss.” I like the special Burroughsian glimmer to names like Appius Applosus, Honus Hasta, and Dion Splendidus. Many of the book’s Latin terms have no connection to actual Latin; they’re ERB experimenting with the idea of the language evolving as an isolate over eighteen hundred years — and also having a good time slinging syllables around.

The two cities are not exact simulacrums of the early Roman Empire, but unusual outgrowths of Roman civilization developing among the environment of Central Africa. The first half of the book uses Erich von Harben’s point of view to explore the peculiarities of Castrum Mare and its caste system established with Roman citizens, a mixed-race second class of non-citizens, and enslaved black tribesmen.

Burroughs flashes his historical research, throwing around words like gladius (sword) and caliga (military boot), and providing lush descriptions of Roman throngs and the packed crowds of the amphitheaters. Von Harben looks at the stands in the Colosseum and discovers how striking and alive it all appears compared to the Ancient Rome of his imagination, which he realizes is essentially frozen pictures, “automatons, who move only when we look at them.”

How different, this! He saw the constant motion in the packed stands, the mosaic of a thousand daubs of color that became kaleidoscopic with every move of the multitude. He heard the hum of voices and sensed the offensive odor of many human bodies. He saw the hawkers and vendors passing along the aisles shouting their wares. He saw the legionaries stationed everywhere. He saw the rich in their canopied loges and the poor in the hot sun of the cheap seats.

You could interpret this passage as the adult Edgar Rice Burroughs recognizing that the dusty school version of Ancient Rome and its language are fakes. He’s intoxicated envisioning how vivid the reality must have been. This is also a prime piece of ERB prose, enticing all the senses, and starting from the high and splendid (“thousand daubs of color”) and descending to a comic note of modernism (“cheap seats”).

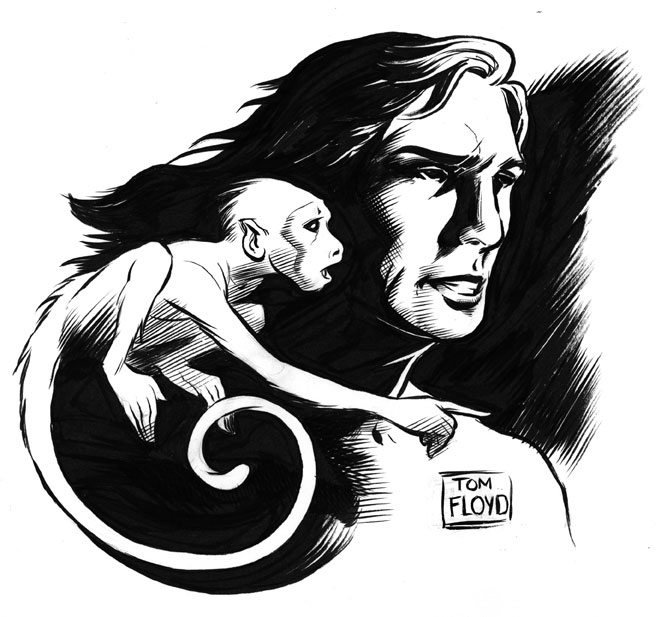

Introducing Nkima

Tarzan receives a new animal companion to complement Jad-bal-ja the lion. In fact, the first word of the book is the animal’s name: Nkima. Tarzan previously received assistance from the Manu, the small monkeys of ERB’s fantasy jungle. But now he has one that has bonded with him and serves as the tiny assistant many heroes need. You can’t expect a golden lion like Jad-bal-ja to carry around clandestine messages.

Nkima doesn’t have a large physical presence in the novel, but his role is a critical one. It goes beyond the job of taking Tarzan’s communication to Muviro and the Waziri so they can rush to the rescue in the spectacular Battle of Castra Sanguinarius. For me and many ERB fans, Nkima’s first appearance completes the Tarzan family. All the major figures of Tarzan’s mythos have now been introduced: Jane, La of Opar, Jack (Korak), Muviro, Jad-bal-ja, and now Nkima, who will inspire the creation of the chimpanzee sidekick Cheeta in the Johnny Weissmuller films.

Considering Burroughs was cutting away the majority of the supporting characters at this point, the little Manu is a welcome presence expanding Tarzan’s character. ERB loved using animal companions in his stories, but usually they were larger beasts: Jad-bal-ja, Woola, Raja, Old White the Mammoth. Nkima is different: an “espionage” animal who can do as much good for Tarzan as the fiercest lion sidekick.

Considering Burroughs was cutting away the majority of the supporting characters at this point, the little Manu is a welcome presence expanding Tarzan’s character. ERB loved using animal companions in his stories, but usually they were larger beasts: Jad-bal-ja, Woola, Raja, Old White the Mammoth. Nkima is different: an “espionage” animal who can do as much good for Tarzan as the fiercest lion sidekick.

There’s an absolutely lovely moment with Nkima when the monkey returns to find Tarzan imprisoned in a Bagego hut: “… little Nkima came down and snuggled in his master’s arms and there he lay all night, happy to be near the great Tarmangani he loved.” Awwww.

The Lost Empire Publishing Adventure

Tarzan and the Lost Empire had a twisted path to magazine and book publication. In 1926, Charles Agnew MacLean, editor of Street & Smith’s The Popular Magazine, requested Burroughs write a new serial for him. ERB responded with the manuscript for “A Weird Adventure on Mars,” later known as The Mastermind of Mars. MacLean rejected it as too gruesome, and soon Ed realized the editor really wanted a Tarzan serial rather than any other of the author’s settings. After long negotiations, Burroughs finally agreed to write a new Tarzan story if the editor promised to pay 10¢ a word — an enormous rate when 5¢ a word was top-tier pay. MacLean conceded to Burroughs’s request, but rejected the manuscript for Tarzan and the Lost Empire (then titled “Tarzan and the Lost Tribe”). The reason for the rejection, according to MacLean’s letter, was that “it is not a real Tarzan story” because it lacks Tarzan adventuring the jungle. Although MacLean offered some legitimate criticisms, such as the problem with having the two different cities, my guess is the editor never intended to purchase anything at the 10¢ rate and was only going through the motions. Burroughs was ticked off (he scribbled “No Ans.” on the top of the rejection letter), but turned around and sold the serial to Blue Book, where it ran in five installments from October 1928 to February 1929. I can’t find a record of what Blue Book paid Burroughs, but it was probably less than 10¢ a word.

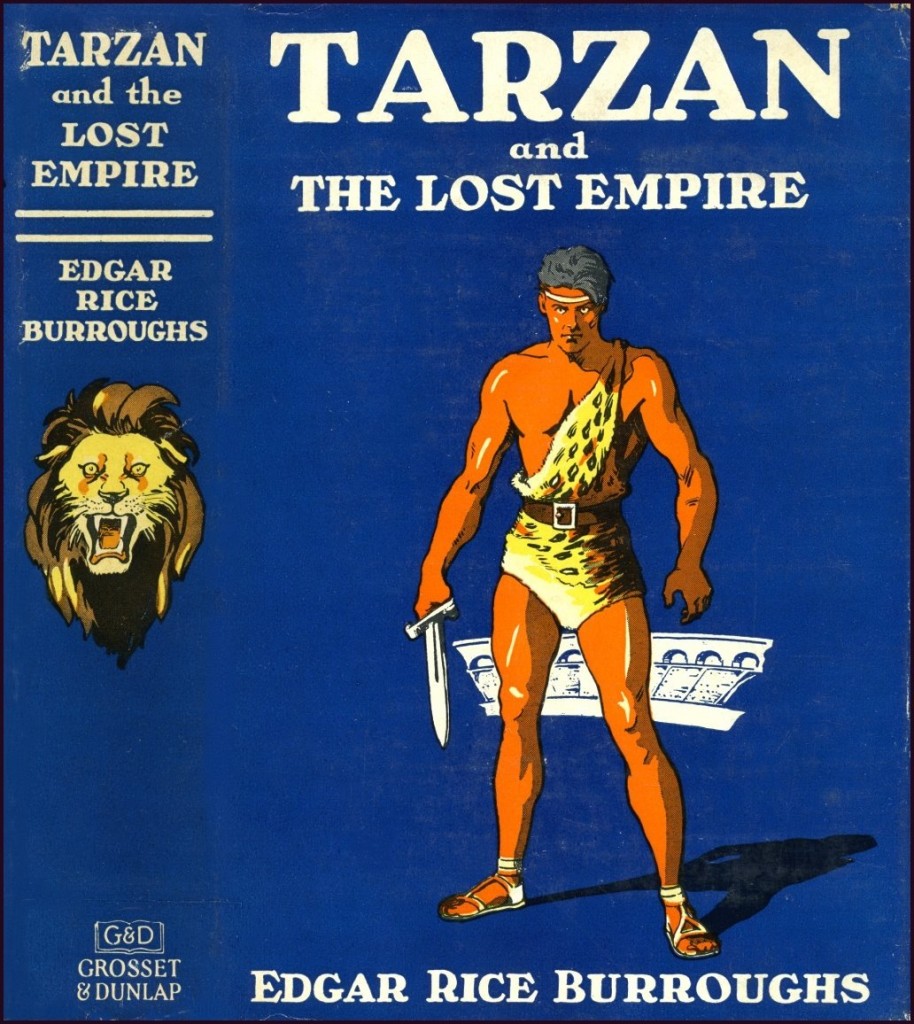

On the book publication front, this was when Burroughs was locked in a tussle with his long-time publisher A. C. McClurg over royalties. Burroughs at last split with the company and looked for a new publisher. He made a deal with Metropolitan Newspaper Services, the company that handled ERB’s comic strip syndication. Metropolitan wasn’t a book publisher, but they agreed to go into that business just to handle Burroughs’s work. Tarzan and the Lost Empire was the first of four books published in the deal, released in September 1929, making it the first Edgar Rice Burroughs novel not published by McClurg. (The second was A Fighting Man of Mars.)

Tarzan and the Lost Empire was also one of the earliest Burroughs novels published as a mass market paperback, the medium that replaced the pulps for adventure reading in the 1950s. Dell released an edition in 1951 with a back cover map of the canyon of Castra Sanguinarius and Mare Castrum. Only 25¢ at your local newsstand! Thus the seeds were planted for the ERB 1960s paperback boom.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is available as an e-book. His most recent publication, “The Invasion Will Be Alphabetized,” is now on sale in Stupendous Stories #19. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a marketing writer. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

It’s been over thirty years since I read this one, but I remember it as decent mid-level Burroughs.

Always been one of my favorites; and I love the term “Filmation Era”.

Someday I’ll probably start rereading Tarzan again but yeah, it’ll have to be in fits & starts, not trying to just mainline through all 24-ish volumes.

I don’t remember exactly which edition I read first — the public library had a bunch of the black-bordered Ballantine Tarzan books on the shelves, but I kind of think my Lost Empire was an old hand-me-down hardcover? No dustjacket, but the covers were red?

Excellent review as always. I would love to hear your thoughts on La of Opar (who I always wanted Tarzan to end up with-Jane always came across as dull) and even more since Tarzan and the City of Gold was the first Tarzan I ever read (in in a Whitman edition) like your thoughts on Tarzan and his ‘fascination’ for Nemone. It was read when I was a pre-teen and confused me no end because the Tarzan movies were a Saturday movie series on TV running over and over so was aware of Jane but Tarzan was acting like he was totally unattached.

I think that as a boy I read nearly everything Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote.