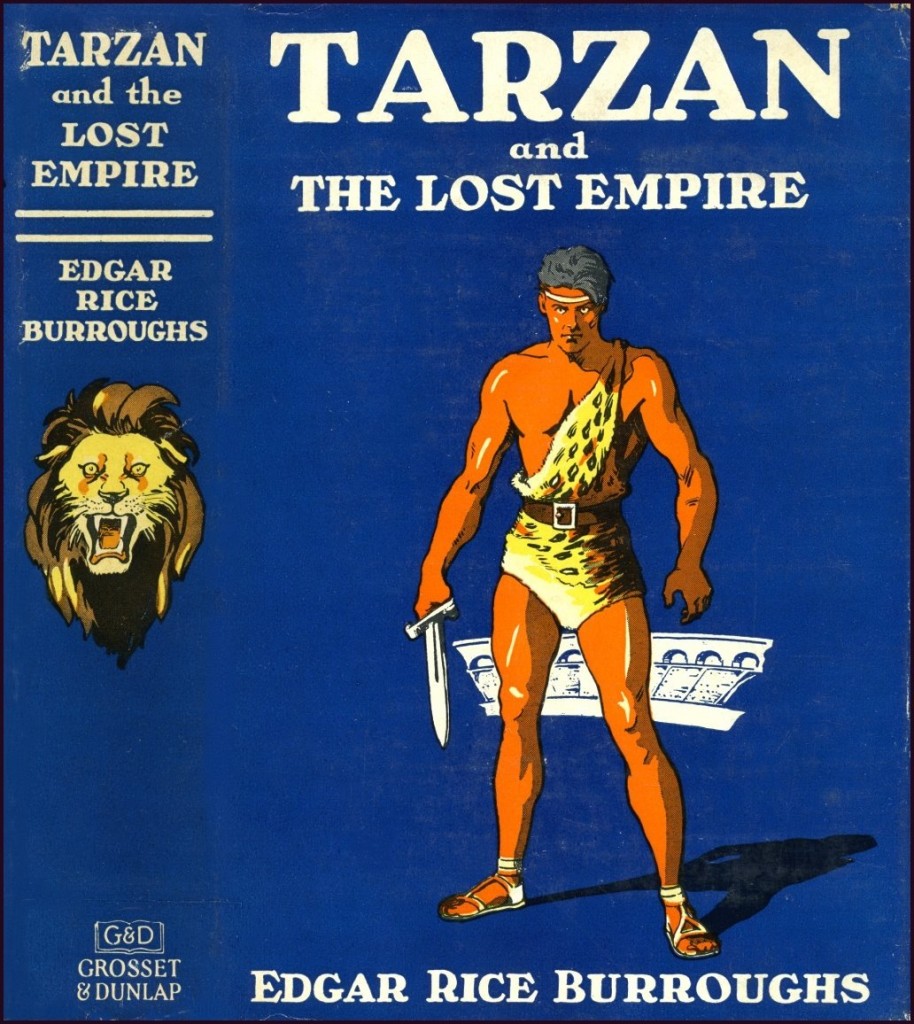

Tarzan Swing-By: Tarzan and the Lost Empire (1928–29)

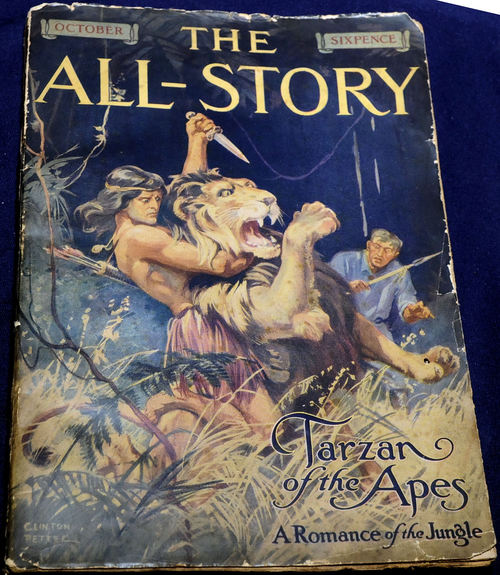

Readers have asked me, but the answer is still no: I can’t tackle the entire Tarzan series the way I did Edgar Rice Burroughs’s other book series, Mars, Venus, and Pellucidar. There are twenty-four Tarzan books, not counting the juveniles, and I’d burn out long before the end if I tried to read them in sequence over a compressed time period.

But since I’m always glad to pick up a Tarzan volume here and there among my other Burroughs readings, I’ll negotiate. I’ll do an occasional Tarzan book “swing-by” to give spotlight time to ERB’s biggest contribution to popular culture. No particular order, just whatever Tarzan adventure grabs me at the moment.

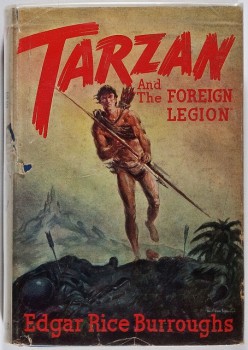

So I’ll start with … let’s see … Book #12, Tarzan and the Lost Empire. Wherein the Lord of the Jungle finds yet another civilization lost in time in the heart of Africa: a remnant of the Roman Empire still living the ancient ways. Tarzan also gets a little monkey sidekick.

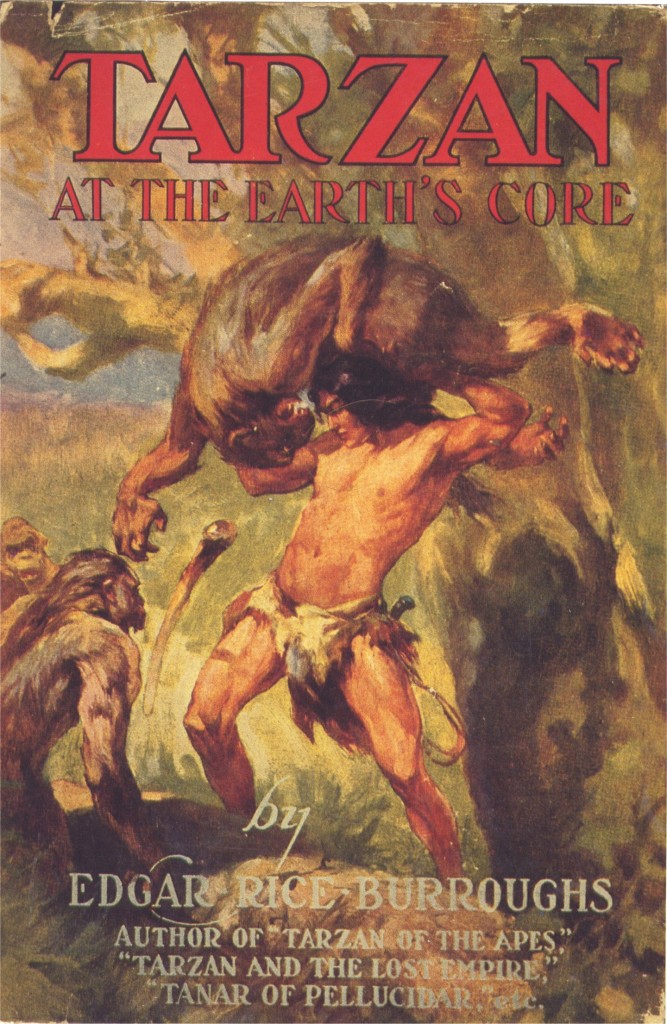

Tarzan and the Lost Empire falls into a period of the Tarzan novels that I think of as the “Filmation Era” because of how much the 1970s Filmation animated series Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle reflects it. After the tenth book, Tarzan and the Ant Men, Tarzan was distanced from the Greystoke legacy and his former supporting cast, and now has the companionship of both Nkima the monkey and Jad-bal-ja the golden lion. Jane vanished except for a single reappearance in Tarzan’s Quest (1936). The plots became standalone and repeated certain formulas, such as Tarzan discovering lost civilizations or facing a Tarzan imposter.

The writing quality of these books was still high in the late ‘20s and early ‘30s, and Burroughs hadn’t lost his skill at executing pulse-racing action set-pieces. But the plotting was often perfunctory as ERB became a bit fatigued with having to go back to the Tarzan well again and again. The story ideas and the prose popped, but the plots often meandered with overstuffed casts and too much incident that doesn’t go anywhere. Tarzan and the Lost Empire falls prey to these faults. But it also contains one of the most interesting hidden civilizations of the series and a setting that energized Burroughs.

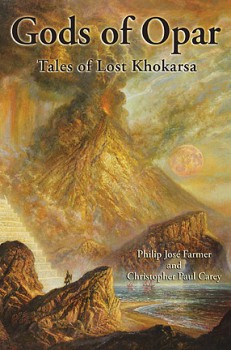

Gods of Opar: Tales of Lost Khokarsa

Gods of Opar: Tales of Lost Khokarsa