Fantasia 2020, Part XXXVIII: Laurin

Tone is one of the most important characteristics of a story, one of the hardest to get right, and one of the hardest to discuss. The feel of a story, what is above and beyond the mechanics of plot or the construction of character or even the specifics of imagery, is a large part of what comes to mind when you think of a story after the story’s done. And tone can be the main concern of a storyteller; it’s a perfectly valid artistic choice to subordinate narrative logic or character motivation or whatever else to the feel the story’s supposed to instill. Or, at least, it’s a valid choice when it works. Which brings up the difficulty in describing tone. It’s often hard to explain what creates it and how well that succeeds, but more, the perception of tone can vary wildly. What works for one person doesn’t necessarily work for another. Particularly when the tone is abstract.

Tone is one of the most important characteristics of a story, one of the hardest to get right, and one of the hardest to discuss. The feel of a story, what is above and beyond the mechanics of plot or the construction of character or even the specifics of imagery, is a large part of what comes to mind when you think of a story after the story’s done. And tone can be the main concern of a storyteller; it’s a perfectly valid artistic choice to subordinate narrative logic or character motivation or whatever else to the feel the story’s supposed to instill. Or, at least, it’s a valid choice when it works. Which brings up the difficulty in describing tone. It’s often hard to explain what creates it and how well that succeeds, but more, the perception of tone can vary wildly. What works for one person doesn’t necessarily work for another. Particularly when the tone is abstract.

Which is all useful to remember in viewing Laurin. A German production shot in Hungary, it was written and directed by Robert Sigl and released in 1988. A 4K restoration’s drawn attention to the movie, and this year’s Fantasia hosted its Canadian premiere. The movie aspires to the tone of a dream or a fable, and whether it succeeds will likely depend on the individual viewer.

It’s set in a small town in Europe in the very early twentieth century. People have begun to disappear, particularly children. Laurin (Dóra Szinetár) is a young girl whose mother has died a bizarre death, and whose father is absent at sea. She’s drawn into the mystery of the missing youths, investigating castle ruins and a mysterious man in black.

And that’s essentially the movie. It aims at creating a dreamlike tone more than a tight dramatic plot, and at only 84 minutes, that’s not unreasonable. It is very slow, and the story simple. Dialogue’s mostly underwritten. Does it work? I would say some aspects, certainly. For me the movie was undermined by its way of telling its story. But that approach is probably central to what the film’s doing, and it’s possible I’m overly concerned with a narrative structure in which Laurin itself is less invested. There is the raw matter for a structured story here, but the movie is more interested in tone than structure. If you can put aside the desire to follow the development of a story and instead dwell in the moment of what you see, that tone might be enough for you.

To go into more detail, let’s start with what clearly works. The film’s gorgeous. There’s an intense autumnal atmosphere in the rich colours of the woodlands and the deep shadows of the night photography. Interiors of homes have the close, overstuffed feel of the late Victorian era (or, in this case, early Edwardian). Contrasting with both is a schoolroom setting that is appropriately muted and drab. There’s a lushness too in the detailed costumes, as there is in the movie’s use of long shots of forests and stone ruins. Note also that despite the feverish tone that emerges there are no special effects to challenge the mood.

Yesterday I wrote about

Yesterday I wrote about

Macbeth is one of the earliest true horror stories, in the sense of a story whose main aim is to play with the emotion of fear, and there’s a notable comic-relief scene with a gatekeeper right after the first gruesome murder. That scene became the subject of a famous essay by Thomas de Quincey arguing (roughly) that the horror’s made greater by contrast. So from the point where horror first began to emerge as a genre, storytellers have been conscious of the effect that comes from balancing horror with the everyday, and even with the comedic.

Macbeth is one of the earliest true horror stories, in the sense of a story whose main aim is to play with the emotion of fear, and there’s a notable comic-relief scene with a gatekeeper right after the first gruesome murder. That scene became the subject of a famous essay by Thomas de Quincey arguing (roughly) that the horror’s made greater by contrast. So from the point where horror first began to emerge as a genre, storytellers have been conscious of the effect that comes from balancing horror with the everyday, and even with the comedic.

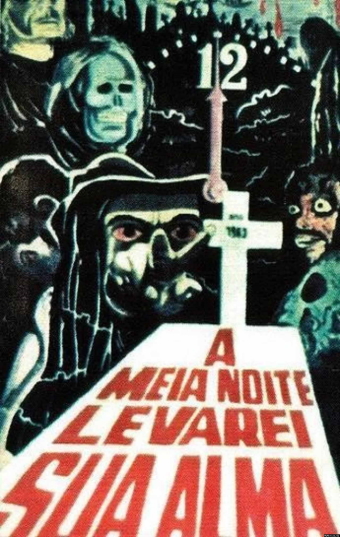

Brazilian director José Mojica Marins died earlier this year at the age of 83. He made low-budget films across a number of genres, with his horror work best known. His character Coffin Joe (Zé do Caixão), introduced in the 1963 film At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul (A Meia Noite eu Levarei sua Alma) is a kind of national ghoul of Brazil. Fantasia decided to honour Marins by making three of his films available on-demand through the festival, and scheduling a talk about Marins with his friend Dennison Ramalho on the last day of the festival;

Brazilian director José Mojica Marins died earlier this year at the age of 83. He made low-budget films across a number of genres, with his horror work best known. His character Coffin Joe (Zé do Caixão), introduced in the 1963 film At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul (A Meia Noite eu Levarei sua Alma) is a kind of national ghoul of Brazil. Fantasia decided to honour Marins by making three of his films available on-demand through the festival, and scheduling a talk about Marins with his friend Dennison Ramalho on the last day of the festival;