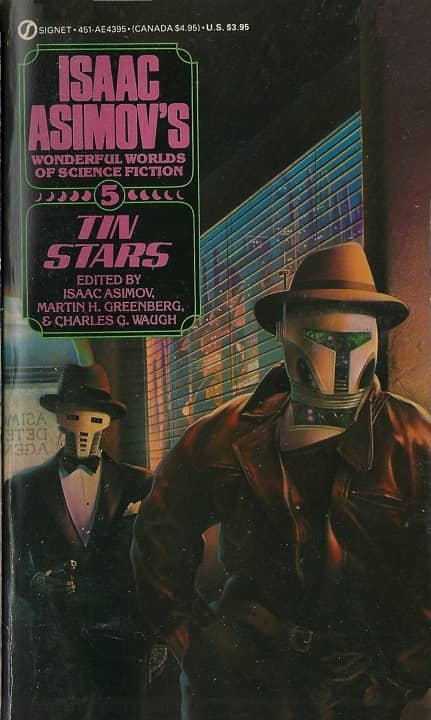

Tin Stars (Signet, 1986), volume 5 of Isaac Asimov’s Wonderful Worlds of Science Fiction. Cover by JAV

Isaac Asimov published more than 500 books in his lifetime. Now Asimov was amazingly productive — averaging around 1,700 words published per day over the last two decades of his life — but no one is that prolific. In later years he became a proficient book packager, working with editors like Charles G. Waugh and especially Martin H. Greenberg to churn out dozens and dozens of science fiction anthologies in which he contributed little more than an introduction and perhaps some editorial guidance.

If this sounds dismissive, oh my friends, it is not meant to be. Asimov was interested in a great many things, but one of his earliest and most enduring passions was short fiction. It was his love for early science fiction pulps that set him firmly on the path towards being a successful SF writer by his later teens, and in his later years he became one of the staunchest champions of the science fiction short story — and in particular those stories and authors that, by the 70s and 80s, were in growing danger of being forgotten. Between 1979 and his death in 1992 he put his name (and the considerable selling power behind it) on numerous SF anthologies and long-running anthology series edited with Greenberg and Waugh, including The Great SF Stories (25 volumes, 1979-92), The Mammoth Book series (6 books, 1988-93), Isaac Asimov’s Magical Worlds of Fantasy (12 books, 1983-91), and others. I don’t know if it was ever made explicit, but it seemed pretty clear that Waugh made the selections, Greenberg handled the rights paperwork, and Asimov was sort of a godfather over the whole process. In any case, the success of these books helped inspire other reprint anthologies, and for many decades life was good for classic science fiction lovers.

Those days, of course, are long over, and mass market reprint genre anthologies are scare as hens teeth today. But when times are tough, the tough get creative, and so I’ve been on the hunt for older science fiction anthologies I may have overlooked all those years ago. That’s how I rediscovered Isaac Asimov’s Wonderful Worlds of Science Fiction — and it is a delight.

Like many of his other popular series it was edited with Greenberg and Waugh, and included 10 volumes published between 1983-90. Each had a different theme: Intergalactic Empires, Space Shuttles, Monsters, Invasions, and so forth. They were generously sized (300-400 pages) and came packed with wonderful stories selected by an editor with a keen eye. These books have never been reprinted, but they’re not hard to find. In fact I recently bought a set of five in nearly brand new condition for significantly less than original cover price.

…

Read More Read More

Last week, I mentioned that I wrote over 40,000 words about Archie Goodwin and Nero Wolfe enduring Stay at Home together. And that the series was inspired by how I felt on the day that Ohio postponed its Primary Voting Day. That scene is below. So, if you’re a Nero Wolfe fan, read on. If not – well, you’re here for my weekly column, so read on anyway!

The elevator made its usual groans of protest as it carried Wolfe’s one-seventh of a ton down from the rooftop plant rooms, where he spent two hours in the morning, and two more in the afternoon, with Theodore Horstmann, tending to 10,000 orchids. It was my personal opinion that the elevator needed more than a two hour recovery period period after having to move him from the ground floor to the roof level. Gravity was not its friend.

No man ever followed routine like Nero Wolfe. Mycroft Holmes looked like an undisciplined lout compared to my employer. Every morning at 11 AM, he came down from the plant rooms, entered the office, greeted me with “Good morning, Archie,” crossed to his desk, and followed a routine there. So imagine my surprise, sitting at my own desk, when I heard him turn and take two steps down the hall, towards the front door, or the kitchen.

I looked up as silence settled in the hall. He had stopped. “Archie, stop this foolishness. Why is the car not ready? Get out here.”

While I am by no means a sigher in Wolfe’s class, working for him has made me a pretty good one. I let one out, got to my feet, and went out of the office. It was Election Day: except, it wasn’t. There were only a few things guaranteed to get Nero Wolfe to venture out of his office and undertake a journey into the wild world outside. And Sunday Mass wasn’t one of them. But he had never failed to sally forth to vote since I had come to work for him. He viewed voting as his side of a solemn contract with the government.

But this April 28th, 2020, was different. The coronavirus pandemic had started parts of America into shutdown mode the prior month. Those who thought that pre-emptive action was a good thing touted the governor of my old home state, Ohio, as the kind of leader we needed in Washington. Others, who probably would have said we should stay out of World War II, thought that it was too soon. Regardless of which side you were on, by early April, it was clear that America was in trouble. Rumors were that Ft. Knox was switching its gold reserves over to toilet paper, because it was harder to find.

…

Last week, I mentioned that I wrote over 40,000 words about Archie Goodwin and Nero Wolfe enduring Stay at Home together. And that the series was inspired by how I felt on the day that Ohio postponed its Primary Voting Day. That scene is below. So, if you’re a Nero Wolfe fan, read on. If not – well, you’re here for my weekly column, so read on anyway!

The elevator made its usual groans of protest as it carried Wolfe’s one-seventh of a ton down from the rooftop plant rooms, where he spent two hours in the morning, and two more in the afternoon, with Theodore Horstmann, tending to 10,000 orchids. It was my personal opinion that the elevator needed more than a two hour recovery period period after having to move him from the ground floor to the roof level. Gravity was not its friend.

No man ever followed routine like Nero Wolfe. Mycroft Holmes looked like an undisciplined lout compared to my employer. Every morning at 11 AM, he came down from the plant rooms, entered the office, greeted me with “Good morning, Archie,” crossed to his desk, and followed a routine there. So imagine my surprise, sitting at my own desk, when I heard him turn and take two steps down the hall, towards the front door, or the kitchen.

I looked up as silence settled in the hall. He had stopped. “Archie, stop this foolishness. Why is the car not ready? Get out here.”

While I am by no means a sigher in Wolfe’s class, working for him has made me a pretty good one. I let one out, got to my feet, and went out of the office. It was Election Day: except, it wasn’t. There were only a few things guaranteed to get Nero Wolfe to venture out of his office and undertake a journey into the wild world outside. And Sunday Mass wasn’t one of them. But he had never failed to sally forth to vote since I had come to work for him. He viewed voting as his side of a solemn contract with the government.

But this April 28th, 2020, was different. The coronavirus pandemic had started parts of America into shutdown mode the prior month. Those who thought that pre-emptive action was a good thing touted the governor of my old home state, Ohio, as the kind of leader we needed in Washington. Others, who probably would have said we should stay out of World War II, thought that it was too soon. Regardless of which side you were on, by early April, it was clear that America was in trouble. Rumors were that Ft. Knox was switching its gold reserves over to toilet paper, because it was harder to find.

…