Tatoonie

In a galaxy, far, far away, Kepler 16b (aka Tatoonie) circles a binary star.

In a galaxy, far, far away, Kepler 16b (aka Tatoonie) circles a binary star.

Next thing you know they’ll discover a race of Wookies.

In a galaxy, far, far away, Kepler 16b (aka Tatoonie) circles a binary star.

In a galaxy, far, far away, Kepler 16b (aka Tatoonie) circles a binary star.

Next thing you know they’ll discover a race of Wookies.

In that spirit, I’d like to pass along this little tidbit I read this morning about a pair of mutant cousins in Serbia who exhibit magnetic powers much like Marvel Comic’s Magneto — minus (so far) the latent megalomania and cool helmet.

Two boys from the central Serbian town of Gornji Milanovac have the rare ability to attract metal objects, acting much like human magnets… Sanja Petrovic, the mother of 4-year-old David, said it first came to her attention “about a month ago.”

“I asked him to fetch me a spoon so I could feed his little brother, and he yelled back: ‘Mom, it sticks!'” Petrovic recalls. “I found him with several spoons and forks hanging from his body.”

The phenomenon is rare and so far medically unexplained. Several similar cases, however, have recently been reported in Serbia, Croatia and Bosnia. “As far as I know, there is no medical or scientific explanation,” said radiologist Mihajlo Dodic, who runs a practice in the Serbian capital, Belgrade. He said the cousins’ magnetism borders on the “paranormal.”

Well, that about wraps it up for normal humans. I thought for sure we had a few generations left before being put out to pasture. I hope the camps they make for us are comfortable and equipped with most amenities.

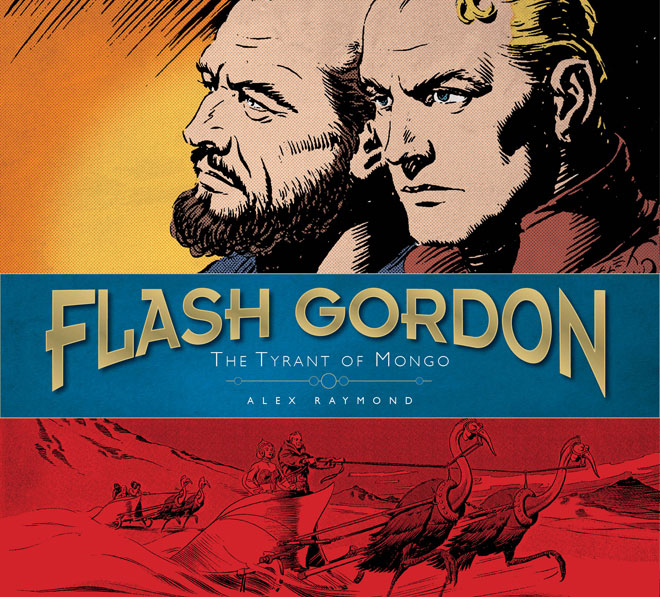

“The Tyrant of Mongo” was the twelfth installment of Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon Sunday comic strip serial for King Features Syndicate. Originally printed between June 12, 1938 and March 5, 1939, the epic-length “Tyrant of Mongo” picks up the storyline where the eleventh installment, “Outlaws of Mongo” left off with Flash and the Freemen having sought refuge in the tombs of Ming’s ancestors. They befriend Chulan the caretaker who joins the Freemen. The flooding of Mingo City has thrown the kingdom into disarray. Flash and a group of Freemen storm the Navy’s flagship only to find its captain only too willing to join the fight against the Emperor.

“The Tyrant of Mongo” was the twelfth installment of Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon Sunday comic strip serial for King Features Syndicate. Originally printed between June 12, 1938 and March 5, 1939, the epic-length “Tyrant of Mongo” picks up the storyline where the eleventh installment, “Outlaws of Mongo” left off with Flash and the Freemen having sought refuge in the tombs of Ming’s ancestors. They befriend Chulan the caretaker who joins the Freemen. The flooding of Mingo City has thrown the kingdom into disarray. Flash and a group of Freemen storm the Navy’s flagship only to find its captain only too willing to join the fight against the Emperor.

Emboldened by their success thus far, Flash and Captain Sudin lead the growing ranks of Freemen in a daring prison break to free Ming’s political prisoners. Naturally, they have walked into a trap. Scores of Freemen are decimated by Ming’s forces. Flash and an injured Sudin manage to escape with their lives. Unexpectedly, Flash and Sudin bombard the prison from their rocketship and rescuing those survivors they can reach attempt to make good their escape.

Crashing into the sea, Flash learns they are short one oxygen tank and heroically stays behind with the sinking ship while everyone else makes their way to freedom. Dale and Zarkov succeed in rescuing Flash, but Zarkov doesn’t believe his chances for survival are very strong. Of course, thanks to Zarkov’s surgical skill Flash does survive and recovers sufficiently to hastily design and oversee construction of a complex series of underground tunnels to house the Freemen. Naturally, their new-found tranquility is short-lived as Ming visits the island to bury his recently-deceased uncle (who Ming had killed when he learned he was plotting against him). A word should be said about Alex Raymond reaching new heights with his artwork in this installment. Raymond’s work was constantly evolving and it retains its power nearly 80 years later.

Part 1 of a 2-part series

Part 1 of a 2-part series

And whether or not Tolkien’s works will stand the test of time is not within our lot to know, so that the Tolkien enthusiast’s need to defend Tolkien’s title of “author of the century,” as a result of the recent Waterstone’s poll of 25,000 readers in Great Britain in 1997, may be unnecessary and even gratuitous. A work like The Hobbit that has already been translated into thirty languages or one like The Lord of the Rings, into more than twenty, has already demonstrated the virtues of both accessibility and elasticity, if not endurance. An author who has sold fifty million copies of his works requires no justification of literary merit.

Jane Chance, Tolkien’s Art: A Mythology for England

Is The Lord of the Rings literature? The answer depends on who you ask. As I see it, four camps exist, each with a different take on the question.

Camp 1, Devoted Tolkien fans. Ask one of these folks and you’re likely to hear, “A Elbereth Gilthoniel! Of course. Need this question even be asked?” For members of Camp 1 the evidence is plain, the case long made for Tolkien’s literary greatness—even if they don’t always offer clear and/or compelling supporting evidence.

Camp 2, Ardent Tolkien haters. An answer by a member of Camp 2 is typically something along the lines of [Sarcasm mode on] “Tolkien’s books had literary merit?” [/Sarcasm mode off] No awful children’s story about Elves and Hobbits and Dark Lords could possibly qualify as literature. At least The Sword of Shannara wasn’t boring.

Ever since interviewing Charlene Harris, I must admit to being a big fan of True Blood. But it’s important to note that the HBO series encompasses far more creatures than just vampires and the vampires that do reside in Bon Temps, LA where all the action takes place, at least adhere to the widely accepted folklore such as adversity to daylight, stakes through the heart, etc.

Ever since interviewing Charlene Harris, I must admit to being a big fan of True Blood. But it’s important to note that the HBO series encompasses far more creatures than just vampires and the vampires that do reside in Bon Temps, LA where all the action takes place, at least adhere to the widely accepted folklore such as adversity to daylight, stakes through the heart, etc.

No daytime sparkly angst here.

But let’s be honest. Between the TV shows and movies of the last five years, vampires are suffering from overexposure. And like any fad that has run its cultural course, nothing says “over” like being slapped on a lunch box come back-to-school time.

Goth Chick’s prediction for 2012 fashion? Vampires are out. Man-made monsters that defy all the laws of nature are way in.

To prove my point, there are already several early adopters in both the big and small screens.

First off, no, this has nothing to do with Terry Brooks…

So I recently saw Conan 3D 2011… and yeah I know what you’re thinking, but I’m not going to go into that because it’s been beaten to death elsewhere, and certainly here on Black Gate. Still, I had to wonder after seeing it, what did the world of Hyboria get for its 2011 dollar?

Considering the movie reviews and box office receipts, whatever the cost for art direction it was far too much. As I watched, I contemplated the words of John Fultz and his thoughts concerning the imagery of the movie when he said… wait, I’m going to go look this up so John can’t complain I misquoted him… Ok, here we go…

The Hyborian Age has never looked so wondrous, splendid, and believable on screen. From the virgin wilderness and Cimmerian villages to the decadent, sprawling cities, the vast monasteries, and the ancient citadels with skull-shaped caves, the movie simply looks fantastic. The costuming too is spot-on and suitably grimy, evocative, and well-designed. Same goes for the props: swords, spears, armor, ships, etc.

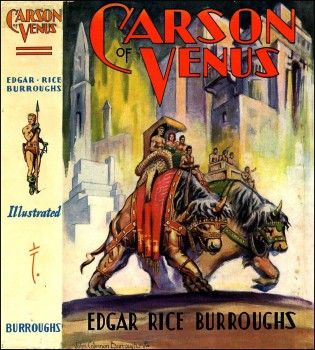

Five years have passed since Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote Lost on Venus, and the world has undergone a startling and disturbing metamorphosis. Something sinister and confusing is taking place in Europe, and across the Atlantic waters the people of the United States are growing concerned at the saber-rattling of Nazi Germany. The poverty-crippled period in which ERB wrote the previous Venus books has given way to a time of escalating fear of a second great war.

Five years have passed since Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote Lost on Venus, and the world has undergone a startling and disturbing metamorphosis. Something sinister and confusing is taking place in Europe, and across the Atlantic waters the people of the United States are growing concerned at the saber-rattling of Nazi Germany. The poverty-crippled period in which ERB wrote the previous Venus books has given way to a time of escalating fear of a second great war.

Does this have anything to do with the next novel of the Venus saga, 1938’s Carson of Venus? Of course not. That the villains of the book are called “the Zanis,” and that they rule through a tyrannical personality-cult dictatorship complete with ritualized salutes, concentration camps, and rampant murder of political undesirables is mere coincidence.

Our Saga: The adventures of one Mr. Carson Napier, former stuntman and amateur rocketeer, who tries to get to Mars and ends up on Venus, a.k.a. Amtor, instead. There he discovers a lush jungle planet of bizarre creatures and humanoids who have uncovered the secret of longevity. Carson finds time during his adventuring in the various warring countries of the planet to fall for Duare, forbidden daughter of a king. Carson’s story covers three novels, a volume of connected novellas, and a final orphaned novella.

Previous Installments: Pirates of Venus (1932), Lost on Venus (1933)

Today’s Installment: Carson of Venus (1938)

Edgar Rice Burroughs was in a creative slump at the close of the 1930s. The success of the Johnny Weissmuller Tarzan films at MGM and the creation of his own publishing company meant a steady flow of revenue, but the famous author found his new fiction getting rejected from the regular magazine markets that had featured him for more than twenty years. Even Tarzan was no longer dependable. Burroughs was not a young man anymore, and the magazine rejections seemed to hint that his best writing years were behind him. At least he could always publish the books through his own company, but the publicity from magazine serialization was an important way to boost sales.

It was during this turbulent time that ERB tried a few experiments. After leaving the Venus series alone for five years, he returned to it with a spy story reflecting the political tensions of the day.

Dear Black Gate Readers,

Dear Black Gate Readers,

Something really cool just happened over on LiveJournal.

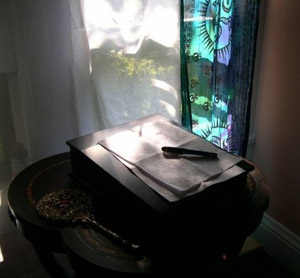

Since I’m sort of still grinning about it, I thought I’d take this opportunity to write about the importance of finding or creating a community of friends and artists who — even if they can’t do anything about your stack o’ rejections, those self-imposed deadlines you keep failing to make, or the number of times your head thumps a desk (in my case, the wall. I don’t know why, but I just find walls more… thumpable… somehow) — are there for you, in whatever way they can be. Even across the miles. Even across state lines! Or oceans!

This is a great age for long-distance friendships, isn’t it? I love it.

Writing is lonesome. And, you know what? THAT’S WHY IT’S APPEALING! You’re one on one with yourself, dueling with your demons, exploring your dreamscapes, loaded to the max with your Tools of Toil: laptop, fountain pen, coffee mug (in my case, tea cup, ’cause coffee? GROSS!), notebooks, dictionary (or dictionary.com), and nothing to disturb you except maybe the dishes, the laundry, the kids (well, NOT in my case, but I know plenty of writers who are parents), the bills, and everything else we have to deal with.

That great escape into lonesomeness is one of the best things about writing.

But sometimes you get discouraged, maybe. And maybe that’s when the lonesomeness is not so great anymore.

So you go to your community. Maybe you post about it on your blog. Anything to make the burden lighter.

And then, in the midst of your writer pals’ commiserations, something like this might happen…

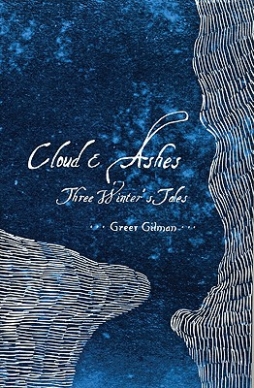

I recently finished reading Greer Gilman’s second novel, 2009’s Cloud & Ashes. I’ve never come across Gilman’s first book, Moonwise, but I’m now looking forward to tracking it down.

I recently finished reading Greer Gilman’s second novel, 2009’s Cloud & Ashes. I’ve never come across Gilman’s first book, Moonwise, but I’m now looking forward to tracking it down.

Cloud & Ashes is a complex, powerful work. It repays careful attention, attentiveness to patterns of imagery, and readiness to work out unknown words from context (this is less a book to read alongside an open dictionary than alongside an open internet connection, which can find obscure, archaic, and dialect words). It demands rereading, and I won’t claim to understand all of it. But I think I can say a few things with confidence — to start with, that it’s a stunning, compelling work of language, and that the apparent occasional difficulty of the text is not only necessary but part of the novel’s overall effect.

In a world much like our own, in a time and place that resembles Scotland or northern England around 1600 in its culture and language use, a generational story of mothers and daughters is played out which derives from and intersects with the seasonal myths of the land. Witches are a real and powerful presence. Companies of guisers travel about, presenting dramas of archetypal powers. And at crucial points of the year, as summer goes out or comes in, everyone takes part in rituals of death and rebirth; a woman must play the part of Ashes each winter, in order to bring in a new spring.

I know, I know. You’ve never heard of Elwy Yost.

I know, I know. You’ve never heard of Elwy Yost.

But you probably didn’t grow up in Ontario in the late 70s and early 80s. Those who did knew and loved Elwy Yost.

Elwy Yost was the host of TVOntario’s Saturday Night at the Movies from 1974–99 and, more importantly to me, the half-hour weekday show Magic Shadows, from 1974 until the mid-80s.

When I was 12 years old in 1976, my after-school ritual was well-established. Walk home from Sir Wilfred Laurier High School, finish homework, eat dinner, and then stretch out on the living room floor, lying on my stomach with my feet in the air, to watch Magic Shadows.

Magic Shadows presented classic Hollywood movies, cut into half-hour serials and introduced by Yost with erudite and infectious enthusiasm. Best of all, Yost had an unapologetic fondness for the occasional monster movie, including King Kong, Gorgo, and others. On those weeks when the main feature would wrap up by Thursday, Friday would feature an episode of a true film serial like The Adventures of Captain Marvel, Mysterious Doctor Satan, or Captain America.

For those who do remember, here’s the animated intro to Magic Shadows on YouTube, and a sample of classic Yost as he introduced the 1954 Marlon Brando pic Desirée. Watching these two clips brought me right back to the late 70s. [Thanks to my friend Todd Ruthman for sending them my way.]

In later years Elwy Yost was overshadowed by his son, Graham Yost, who moved to California to become a screenwriter (Speed, Broken Arrow) and writer/director (of the HBO miniseries The Pacific). Speed was the last movie Yost hosted before retiring from Saturday Night at the Movies in 1999. Elwy Yost wrote Magic Moments from the Movies and two young adult novels, Secret of the Lost Empire and Billy and the Bubbleship, and a mystery novel, White Shadows.

I would develop a lasting fondness for pulp fiction when I discovered pulp magazines later in high school. But it was Elwy Yost who showed me that the best adventure fiction — yes, even monster movies — deserved to be preserved and studied with the same loving attention as the finest cinema. He was a man who loved film, and who communicated that love to an entire generation of young Canadians.

I miss him already.