The Adventure Continues: the Return of Renner and Quist

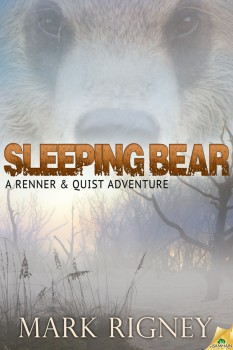

When I first dreamed up my odd-couple pair of Renner & Quist, one of the many goals I had in mind was to write their stories specifically and consciously as adventures. This was not perhaps the most sensible decision, given a literary market polarized between nominally realistic “grown-up” fare and the highly fantastical tomes aimed at teens. (I shall not deign to even mention Romance; call me biased, go ahead. I can take it.) Nor did my conception of Renner & Quist allow for them to don armor, wield swords, or inhabit some far-flung or alternate world. No, these two, Reverend Renner being a Unitarian Universalist minister and Dale Quist a former P.I. and ex-linebacker, required a contemporary setting; to emplace them elsewhere would be to guarantee that any stories woven around them would be untruthful.

When I first dreamed up my odd-couple pair of Renner & Quist, one of the many goals I had in mind was to write their stories specifically and consciously as adventures. This was not perhaps the most sensible decision, given a literary market polarized between nominally realistic “grown-up” fare and the highly fantastical tomes aimed at teens. (I shall not deign to even mention Romance; call me biased, go ahead. I can take it.) Nor did my conception of Renner & Quist allow for them to don armor, wield swords, or inhabit some far-flung or alternate world. No, these two, Reverend Renner being a Unitarian Universalist minister and Dale Quist a former P.I. and ex-linebacker, required a contemporary setting; to emplace them elsewhere would be to guarantee that any stories woven around them would be untruthful.

This is not to say that I’m against high fantasy; quite the opposite. I’m here, aren’t I? For further proof, take a gander at my Black Gate trilogy concerning Gemen the Antiques Dealer.

But not all ideas trend that direction and with Renner & Quist, I knew I had nearer waters to chart. Now that their second novella, Sleeping Bear, is out in the world, and with their first proper novel, Check-Out Time, very much in the production pipeline, it seems high time to explore what remains, in the 21st century, of that cracking good term, “adventure.”