Concerned by Moral Imperatives: An Interview with D.G. Compton

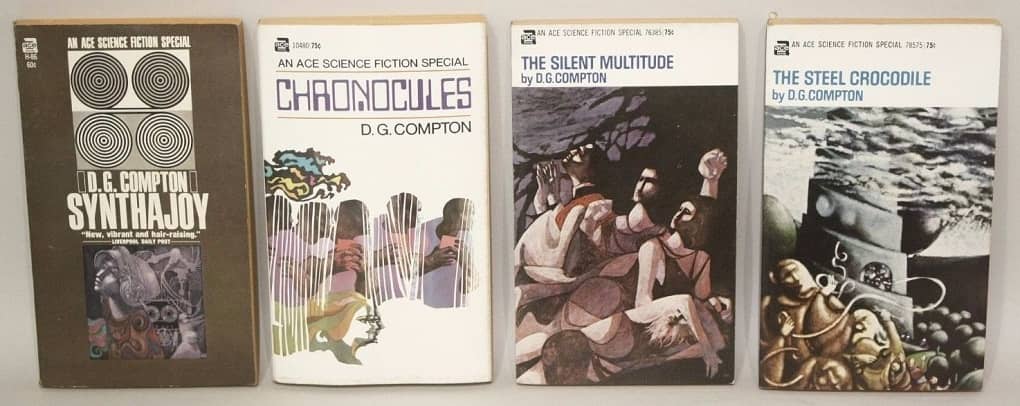

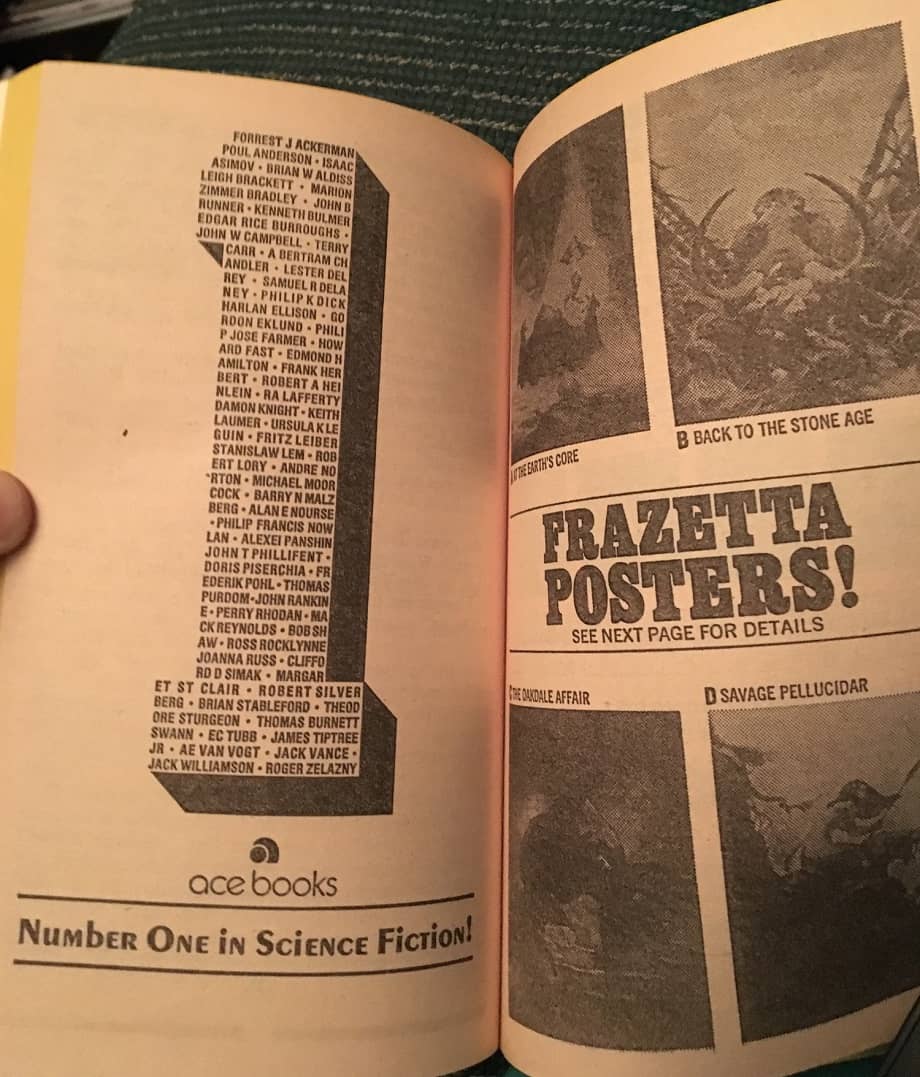

D.G. Compton’s early Ace paperbacks. Covers by Leo and Diane Dillon.

David Guy Compton came to prominence in science fiction in 1968 with the publication of Synthajoy in the prestigious Ace Specials series edited by Terry Carr, although it was actually his second Ace book, preceded by The Silent Multitude (1966) This was quickly followed by The Quality of Mercy (1970), The Steel Crocodile (1970), Chronocules (1970), Farewell Earth’s Bliss (1971; published in England in 1966) The Missionaries (1972). DAW then brought out The Unsleeping Eye (1974), which was published in England as The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe and filmed as Death Watch. Windows (1979) and Ascendancies (1980) followed from Berkley, after which he tended to fade from the American publishing scene, although his work, notable for its unflinching intensity and mature treatments continues to command respect. His novels with the preoccupation with the impact of media on individual lives were in many ways well ahead of their time. The Unsleeping Eye, for instance, is about a report who has television cameras implanted in his eye, so that he can film the last days of a dying woman for a voyeuristic audience of what we would today call “reality TV” addicts.

This interview was recorded at the Nebula Awards weekend in New York, May 12, 2007, where Compton was present to receive SFWA’s Author Emeritus award. It originally appeared in The New York Review of Science Fiction, December 2007, and was reprinted in Speaking of the Fantastic III (2011).

You’ve mentioned that you have a new book coming out —

Oh, I did not say that. I have written a new book. Whether it is coming out or not is another matter. I already have a couple science fiction novels that haven’t been published over here anyway. And to make matters worse, this book isn’t even science fiction. So I have few hopes that it will actually be published. It was just something I had to do.