Concerned by Moral Imperatives: An Interview with D.G. Compton

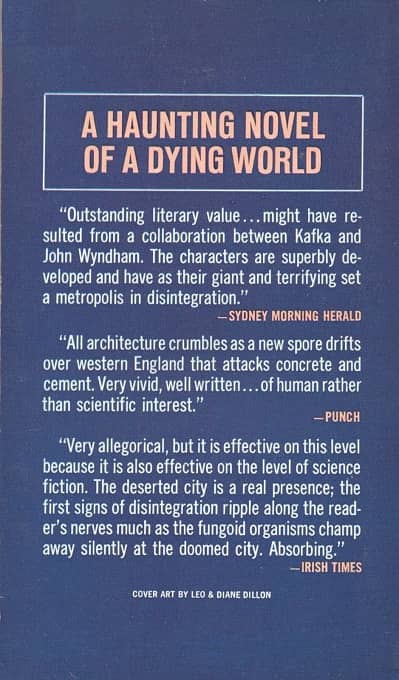

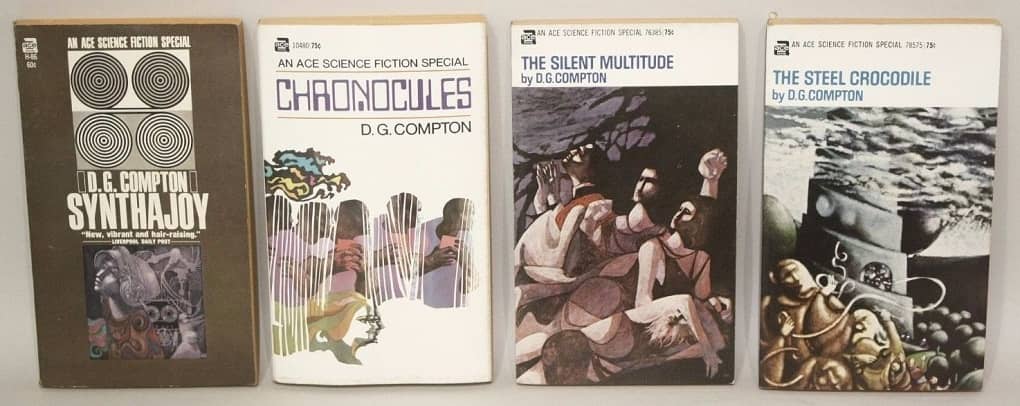

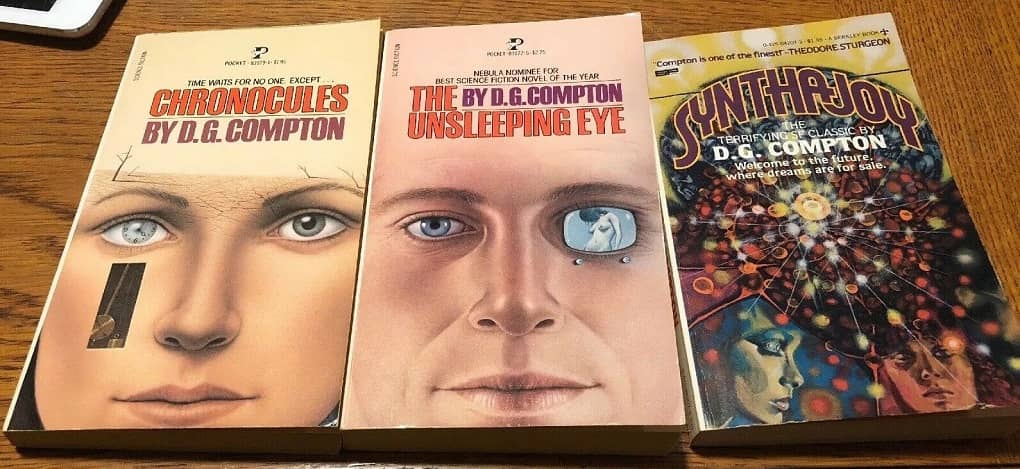

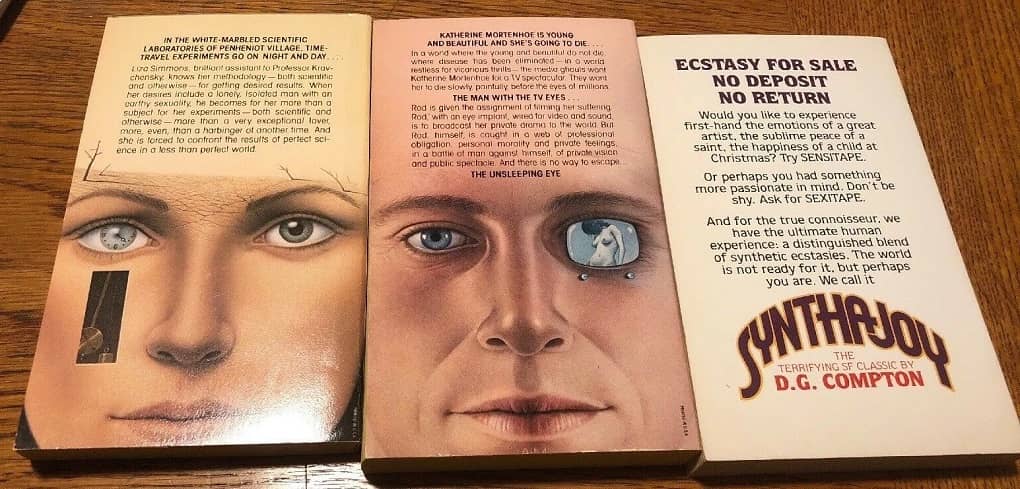

D.G. Compton’s early Ace paperbacks. Covers by Leo and Diane Dillon.

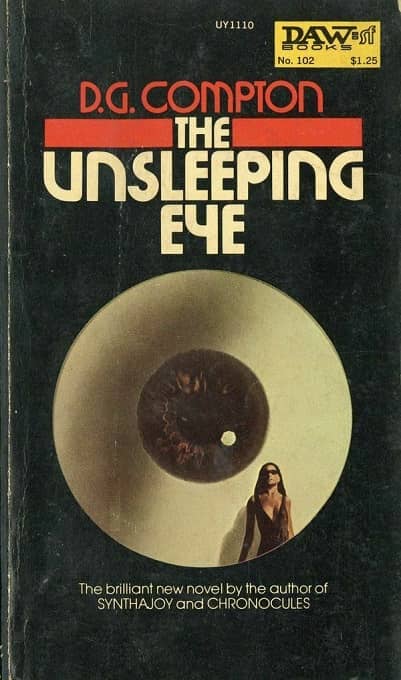

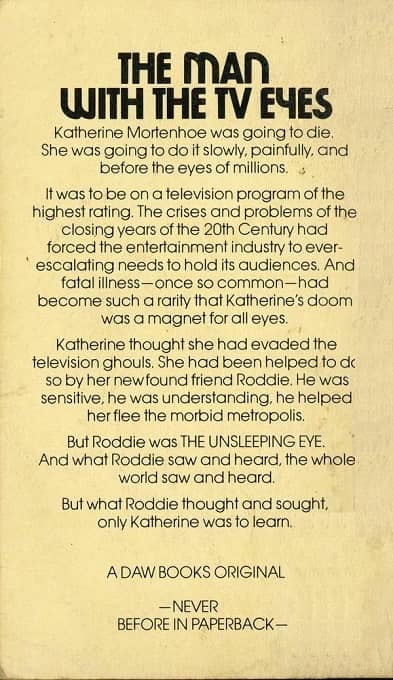

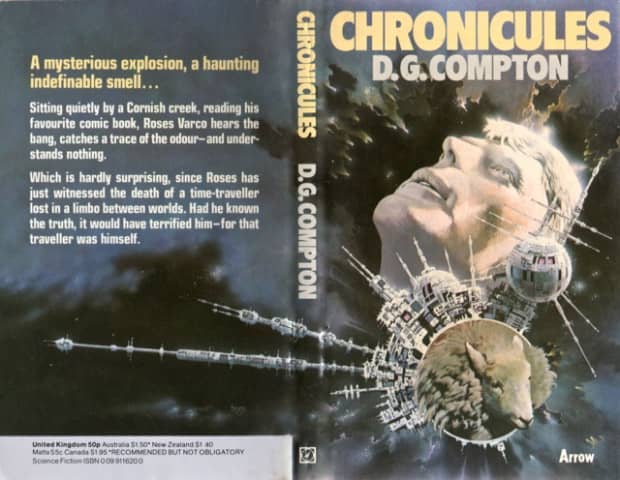

David Guy Compton came to prominence in science fiction in 1968 with the publication of Synthajoy in the prestigious Ace Specials series edited by Terry Carr, although it was actually his second Ace book, preceded by The Silent Multitude (1966) This was quickly followed by The Quality of Mercy (1970), The Steel Crocodile (1970), Chronocules (1970), Farewell Earth’s Bliss (1971; published in England in 1966) The Missionaries (1972). DAW then brought out The Unsleeping Eye (1974), which was published in England as The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe and filmed as Death Watch. Windows (1979) and Ascendancies (1980) followed from Berkley, after which he tended to fade from the American publishing scene, although his work, notable for its unflinching intensity and mature treatments continues to command respect. His novels with the preoccupation with the impact of media on individual lives were in many ways well ahead of their time. The Unsleeping Eye, for instance, is about a report who has television cameras implanted in his eye, so that he can film the last days of a dying woman for a voyeuristic audience of what we would today call “reality TV” addicts.

This interview was recorded at the Nebula Awards weekend in New York, May 12, 2007, where Compton was present to receive SFWA’s Author Emeritus award. It originally appeared in The New York Review of Science Fiction, December 2007, and was reprinted in Speaking of the Fantastic III (2011).

You’ve mentioned that you have a new book coming out —

Oh, I did not say that. I have written a new book. Whether it is coming out or not is another matter. I already have a couple science fiction novels that haven’t been published over here anyway. And to make matters worse, this book isn’t even science fiction. So I have few hopes that it will actually be published. It was just something I had to do.

[Click the images for larger versions.]

Most American readers probably think of you as a figure of the 1960s and early ’70s, for books like Synthajoy and The Unsleeping Eye —

[Compton shows two books.]

These two came out in the mid-’90s.

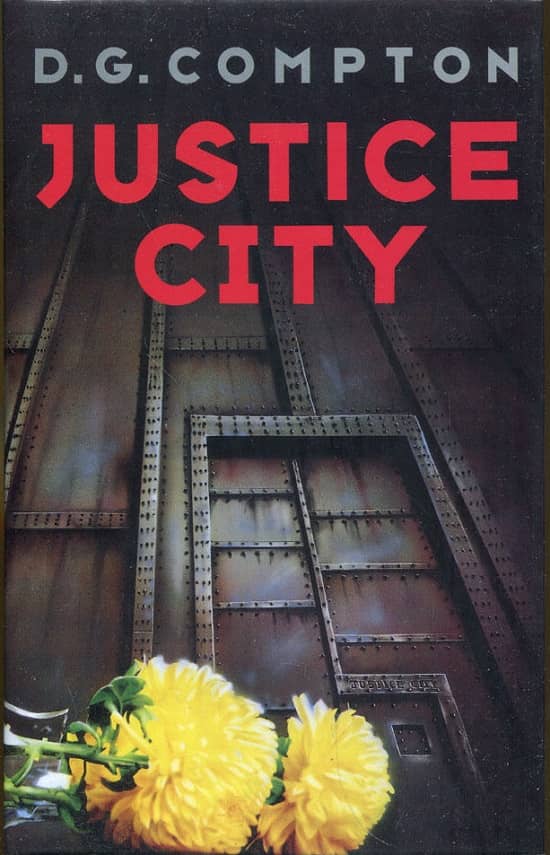

Justice City and No Man’s Land. Are these science fiction?

Published by Gollancz, yes. They are both science fiction.

Justice City (1994)

They’re packaged to look like mysteries.

That one [Justice City]is made to look like a mystery but it’s mostly science fiction, and this one [No Man’s Land] is entirely science fiction.

It even says so. But the Americans have never seen these.

Which is as it suggests, no wars, no crime, no men, no problem. No Man’s Land. But one has to have problems, doesn’t one?

What got you into science fiction in the first place?

My publisher. I had been writing some crime novels, and they weren’t very good, and I decided I would do something different. I had an idea I liked about population control. This was way back whenever it was, early ’60s, I suppose, and I wrote a book. I sent it off to a publisher, the publisher being Hodder & Stoughton in England. They said yes, they would do it, and it was science fiction. And I, who had never even read any science fiction, apart from H.G. Wells, I suppose, and Jules Verne, I said, “Oh, is it science fiction? All right? I don’t mind. You can call it what you like, but publish it.” So is how I got into science fiction.

After it came out as science fiction and was reasonably well received, it made me think, well, I had better do another, hadn’t I? My images of science fiction were so crude at that time that really I thought that I needed a spaceship and mad scientist and a monster. I couldn’t do the mad scientist or the monster, but I did the spaceship. It was a utopia set on Mars. So that launched me further into science fiction. I was very lucky because I had entered a ghetto, a very friendly ghetto that has supported me more or less ever since.

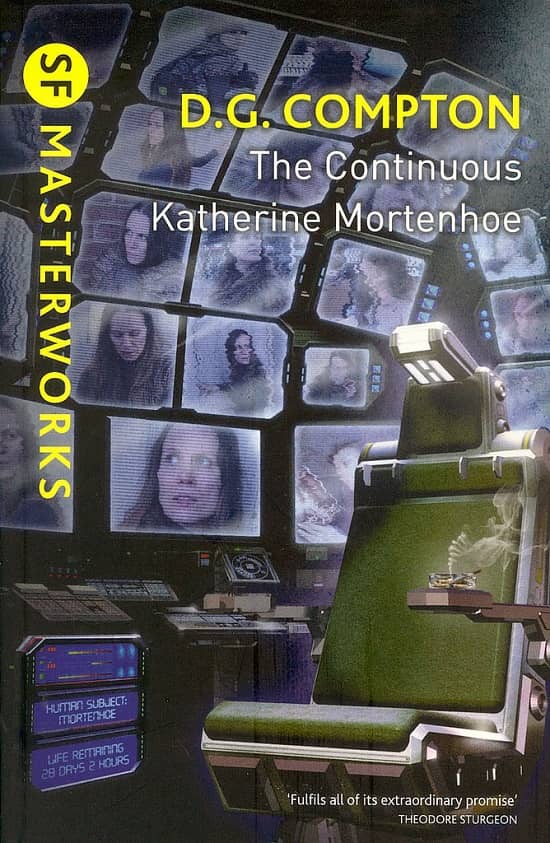

SF Masterworks edition of The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe (2012)

Somehow you managed to match the temper of the times in science fiction. I mean a book like The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe or Synthajoy were both very much cutting-edge science fiction when they came out, particularly all this material about how media controls our lives, implants, etc. It’s almost proto-cyberpunk.

I, you see, am absolutely not a scientist in the smallest way. I had one of those English, very specialized educations, that young men used to have. I don’t think it happens anymore. I studied only modern languages and English, really, so science was out. I was simply responding, as you have said, to things that were going on around me, and using science fiction gimmicks, such as the camera in Katherine Mortenhoe, as a metaphor for what was going on around me.

I notice that in the Algis Budrys introduction to the Gregg Press edition of Synthajoy, that he remarks that much what you wrote about mind-control and electrical implants were almost being supported by experimental science at the time. Were you following any of this at the time? He mentions such things as the discovery that if you put a wire into a rat’s brain and hook that up to a button, it will press the button continuously, neglecting food and water and all else until it dies.

That’s very much the sort of popular science stuff that I as a non-scientist would have picked up out of the media or the general press and latched onto as something I could develop. The Steel Crocodile grew out of a book I did indeed read — the man’s name escapes me [William Sargent, The Unquiet Mind –DS] — he was a brain scientist who claimed that, given access, he could indoctrinate any civilization within a couple of years with a new religion. I thought, that’s a good idea, maybe I could use that. But anyway, this was all very pop science.

You mean you read things like New Scientist –?

Compton: No, no, I never read anything that claimed to be scientific. I have not been interested, basically. I am very interested in society’s reactions to what is offered them by science and things that they pick up and the things that they don’t, but it’s not a subject, basically that I understand. I don’t even think I understand the scientific thought process. That’s my problem.

How about the science-fictional thought process? As you came to be published more in science fiction, did you develop a more conscious sense of being a science fiction writer?

I have to be honest and say that since even when I became a science fiction writer, I did not research the media. I should have gone out and read a lot of science fiction, but I never thought of myself as any sort of a writer. I was writing what was interesting me, and the science-fiction convention, which I only understood in a very clichéd and obvious way, gave me metaphors, a way of talking about things in, I hope, an interesting an unusual fashion.

What got you writing at all? Have you always written for a living?

I always thought of myself as a writer. From a very early, school-day age, I had a facility on the page. I was glib. I was literate. As soon as I left school, basically, I went off to become a writer. I went to a rural cottage somewhere and I was going to be a writer. I was twenty-one years old and just out of the army and I sat down at my desk, armed with my facility, but rapidly discovered of course that I had absolutely nothing whatever to say. I then realized, of course, that there are two aspects of being a writer. One has to be able to write and one has to have something to say.

This was a very disheartening thought, because that meant I had to go out and get a job, various shit-jobs. I was a postman, a window-dresser, a bank guard. I worked on the docks. I just did things and things and collected en route a wife and two children. I did ten years of that, and then I got a very small inheritance, and then my wife, brave, brave, crazy woman, said, “Look, you’ve always said you were going to be a writer. Come along, do some writing.” And I packed my job in. I was a door-to-door salesman at that time. Very bad at it, with my stammer apart from anything else, I didn’t make a very good salesman.

So I sat down and wrote radio plays. And for two or three years I wrote and sold avant-garde radio dramas in England and then in Germany. I got myself a German translator and I think he made me much better than I actually was. He was a very good man.

And while I was doing that I started writing the crime novels, and after that, as I told you, I drifted into science fiction. The radio-play-shaped ideas stopped coming.

|

|

Sometime after the end of the 1970s, I stopped noticing new books from you. Were you actually silent for a while?

Yes, I think I ran out of science-fiction-shaped ideas. I was working in the condensed book department of the Reader’s Digest by day, and I was condensing popular stuff, and I was therefore understanding the market tastes a little more. This was the time when the gothic romances were very popular, and I though, My God, I can do this. Victorian pastiches, very heavily plotted. I have always loved plot. So I did half a dozen of those, under a pseudonym, as a woman, Frances Lynch. It isn’t a secret. Those basically failed. I never achieved the sort of takeoff into big-sellerdom that I had hoped for. People who understood the business said, “The trouble with you is the fact that your tongue is in your cheek shows. It shows on the page that you’re really not quite taking this seriously. Conviction isn’t there.”

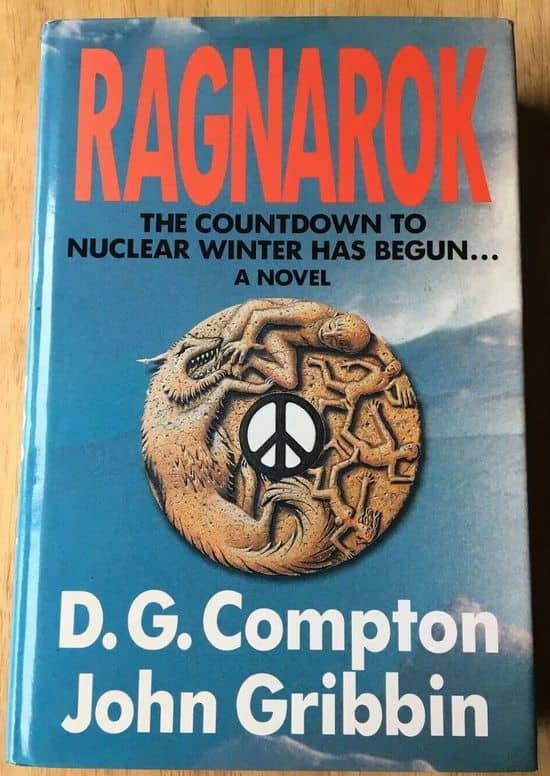

So after doing a half a dozen of those, which probably was the six years you’re talking about, of my absence, I did nothing at all, being very disheartened, until my agent found me a collaborator. I did one book with John Gribbin, Ragnarok, which is a political thriller dealing with terrorists, good terrorists who were holding the world to ransom. John Gribbin is a volcanologist. He is a scientist, a physicist, and had a theory that if you exploded a very small explosive device in the right place off the shores of Iceland, this would create a vast atomic eruption that would bring a long winter, a three-year dust cloud, so you could hold the whole world to ransom. We did out thriller along those lines, which did all right. That was sort of science-fictionish, so I got back into science fiction after that.

Now that you are writing science fiction consciously, as opposed to when you were doing it without knowing it was science fiction, does this change your expectations of what the book should be?

Never. Absolutely never. These are books of character, of personality, of an individual who is changed. It’s the classic structure that well-made novels have, but I’m centered in this. I’m interested in the evasions of people’s lives, and the things that happen to make them recognize the evasions, and possibly cling to them nevertheless. I don’t often have happy endings. There has always been a feeling, I gather, in fandom, in America anyway, about my books, “Oh, he’s all right but he’s so depressing.”

Well, that’s probably fair. I probably am, and my latest non-science-fiction one is probably the most depressing of them all, which is why I have a suspicion that it will never find daylight.

You mean it won’t be published here in the States, or anywhere?

Anywhere. I have become very involved, politically almost, in the assisted suicide movement with Oregon’s record over here, and I became involved up in Maine when we had a referendum. My latest book grows out of that interest and concern. Not exactly a thigh-slapper.

I see this in some of your earlier work, such as The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe [published in the US as The Unsleeping Eye].

Indeed, so it isn’t new.

|

|

The Unsleeping Eye (DAW, 1974, cover by Karel Thole)

What I think we can say about that book is that it might be genuinely prophetic. It seems to be describing reality TV. It is probably only a matter of time until somebody does a reality TV show with the dying.

With the dying, yes. Did you ever pick up the movie?

No, I didn’t.

Ah, I am not surprised. It came and went.

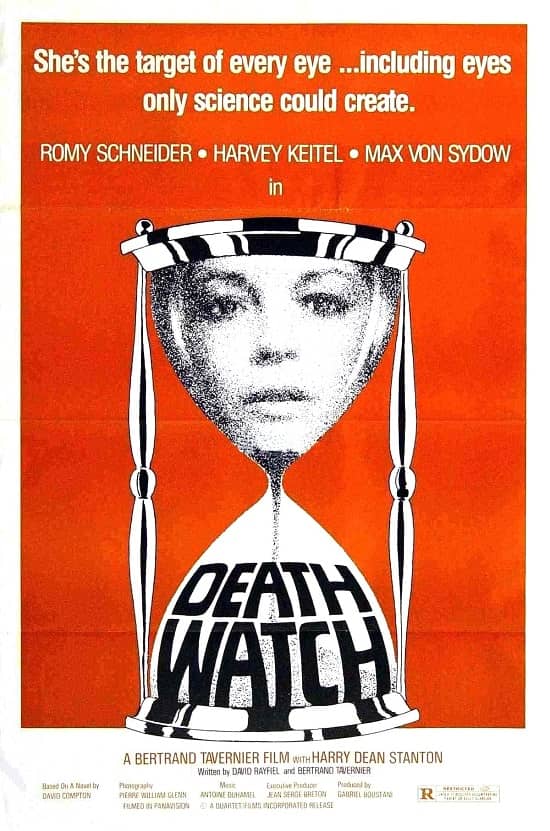

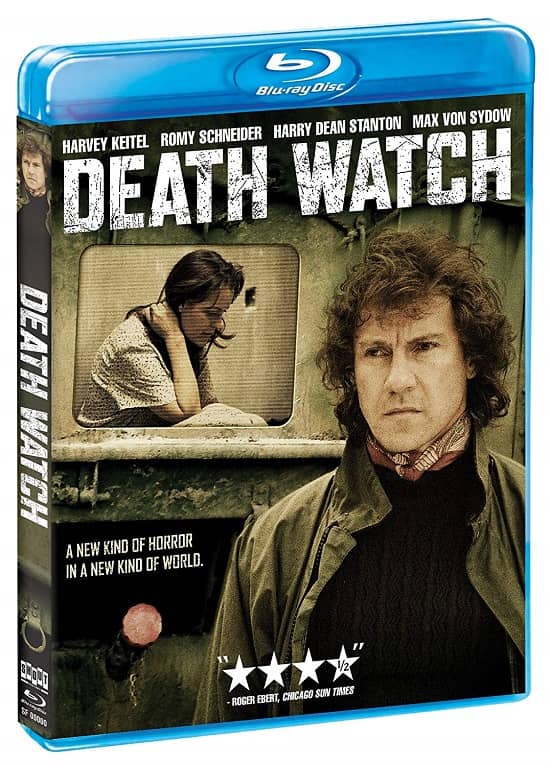

Death Watch poster

Was it called The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe?

It was called Death Watch. Bernard Tavernier the French director did it with Harvey Keitel, Romy Schneider, Harry Dean Stanton, and Max Von Sydow. There were nice people in it. A lovely movie in fact. But it was early and it had a downer at the end, and it never gained universal release. It went around the art houses. At Brown Bear Festival a couple years ago in Milford Pennsylvania they featured it. I was pleased. It’s, what? Thirty years old now? Yes, thirty years old.

Is it available on DVD?

No, only on VCR. That’s a problem.

If it’s VHS, at least you can still find it.

Yes, sure. I have a copy. I am very fond of it. I was very lucky. It was early on in Harvey’s career, and he gives a very nice performance. It was a film that I think stuck perhaps too reverentially to the book. I think maybe some more liberties ought to have been taken. But I like it.

Death Watch DVD (2012)

You’re very fortunate as far as authors go. Most author bemoan what is done to their books in the movies.

My favorite story, which luckily you haven’t heard so I will tell it again, is that after I had heard from the director, who I didn’t know anything about, that he wanted to make it, and my agent said, “Yes, he’s reputable, so go on and have a talk.” I went along expecting a clichéd, cigar-chewing guy, I and I was going to cry all the way to the bank after he had signed the contract, you know. First of all the image was completely wrong. It was a lithesome young Frenchman, rather elegant and thoughtful. I finally came down to the classic cliché question, “Tell me, why do you really want to make a film of my book?” He said, “There was one phrase in it that told me I had to make it, and it’s when there’s this dying woman and you write that ‘she has the possibility of joy’.”

I tell you this is utterly true. That sentence was the most important thing in that book for me and he had picked those six words out as his reason for making it. You can’t get much luckier than that, can you?

No, you can’t.

Utterly phenomenal. [Laughs.] They believed in it and they all worked for peanuts, because they couldn’t get any decent, major Hollywood funding. And I’ve a feeling that if they hadn’t been so reverential and had picked it over a bit, it might have been a better film. But there you go.

|

|

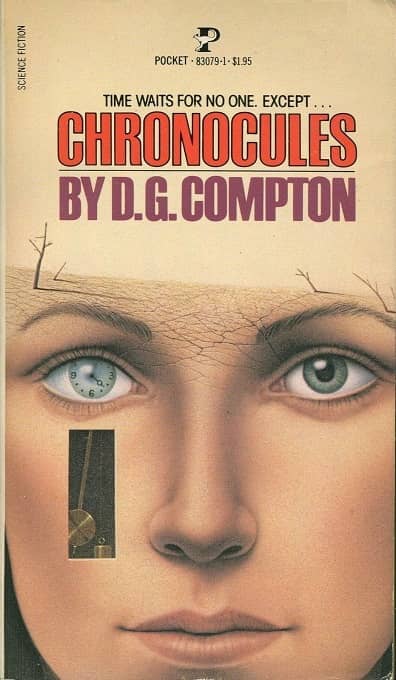

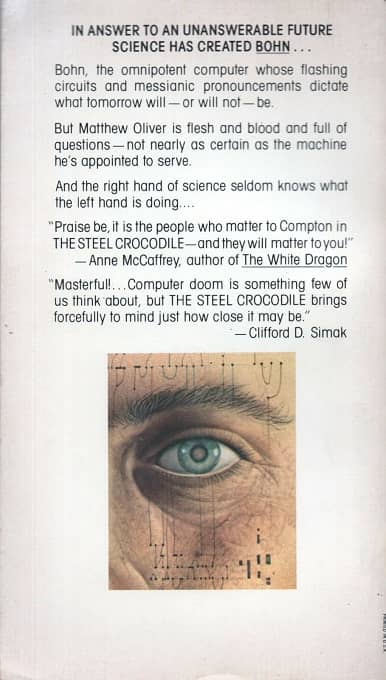

Chronocules (Pocket, 1980, cover by Alan Magee)

It might have been a worse film. It might have starred Arnold Schwarzenegger and had an upbeat ending.

That was why Hollywood wouldn’t have it. They told Tavernier, “Yeah, we love it, but you really have to give it a happy ending.” They really did.

This gets back to the whole subject of downbeat endings. Wouldn’t you agree that the reason you have a downbeat ending in a story is that it’s the honest ending?

Usually, that’s my experience. But then that isn’t the reason that people go to the movies, is it? They go to the movies to feel good. I can understand this. You read books, probably, if you don’t mind having to pick yourself up and dust yourself off afterwards after you’ve finished the final page. It is a different medium.

|

|

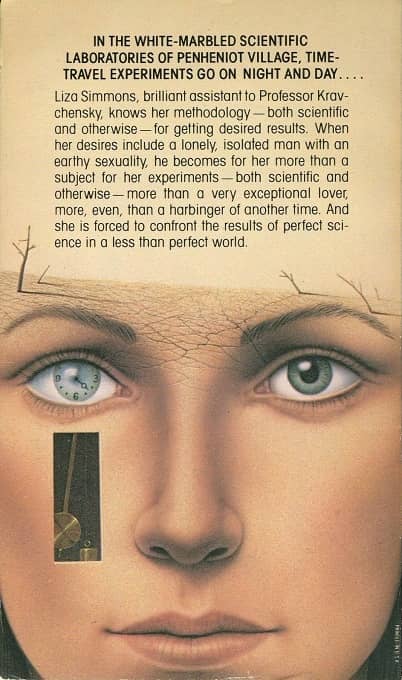

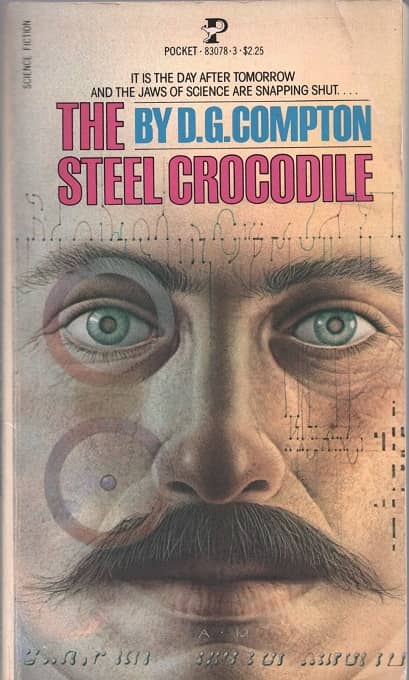

The Steel Crocodile (Pocket, 1980, cover by Alan Magee)

Surely if you just say, “I’m going to write books with upbeat endings because they are more commercial,” what you are going to produce is lies.

I would certainly say that, only maybe you and I have a view of the world that isn’t generally shared. It’s very interesting that you should say that. I have always been an admirer of Ursula Le Guin. And the other day I saw that she has a new book out. That heartened me because I think she’s older than I am and I’m beginning to feel a bit written out, and what else is there to say, all that stuff, but I think her new book is very fine, and she is as positive-thinking as she always has been. It’s a book with an upbeat ending. It’s lovely. I was so hoping that she would be here, but she never travels now. [The new Le Guin book being referred to is Voices. –DS] I would have loved to have talked to her with the problems I have. There’s enough doom and gloom out there. Do I really want to add to it?

Maybe you want to add some understanding of it.

Maybe.

As opposed to merely bemoaning.

I know. I know. Maybe helping other people. Yes. There you go. But I certainly have problems now with justifying covering more pages with more depressing squiggles.

|

|

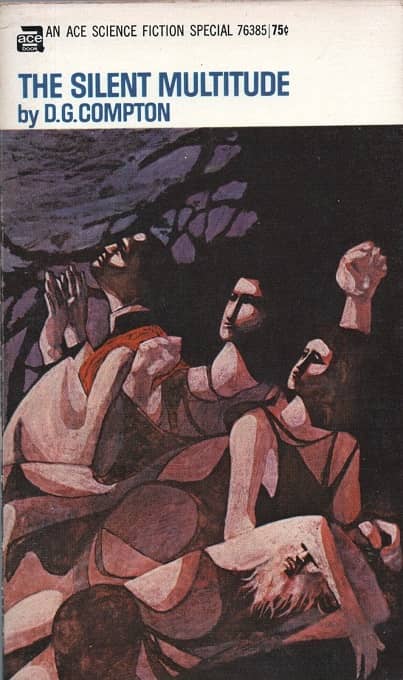

The Silent Multitude (Ace, 1966, cover by Leo Dillon and Diane Dillon)

I am thinking of that scene in Shakespeare in Love where the Queen says of his latest play, “That’s very nice, but something more cheerful next time.”

[Laughs.] Right. Yes. That’s where I’ve gotten. My wife once got rather worried looking at my oeuvre in general. Most of them end with the woman dying or being put in a mental home or being carted off, or whatever. One reason for that of course is simply because I use so many strong central women characters. I was a feminist almost before the word was invented. I have always been pro the woman’s place in the intellectual and power-structure world. I do remember early on over the first three or four, I read several reviews speculating on whether D.G. Compton was a man or a woman. I was really very pleased that I fooled them. [Laughs.]

Budrys talks about that in the introduction to Synthajoy. He cites a line in which female protagonist notices she is sweating under her bra, and something about worrying about her shoe size, and this is not something that would come from male observation.

Well, there you go. I am glad I fooled him too.

Chronicules (Arrow, 1976, cover by David Bergen)

You only did it briefly. Is this all from a sense that women aren’t empowered enough in society, or that women aren’t represented enough in fiction? There was a time in which science fiction notably did not have a lot of women in it.

When Hodder published Katherine Mortenhoe they said, “You can’t have a woman’s name in the title. It’s science fiction. You can’t.” As simple as that.

I am simply a great admirer of… Oh, God… womanliness. A woman’s views, a woman’s position.

I suppose I cannot think of a novel that has a really strong, but at the same time rounded and real woman as a lead character. Perhaps that’s my ignorance.

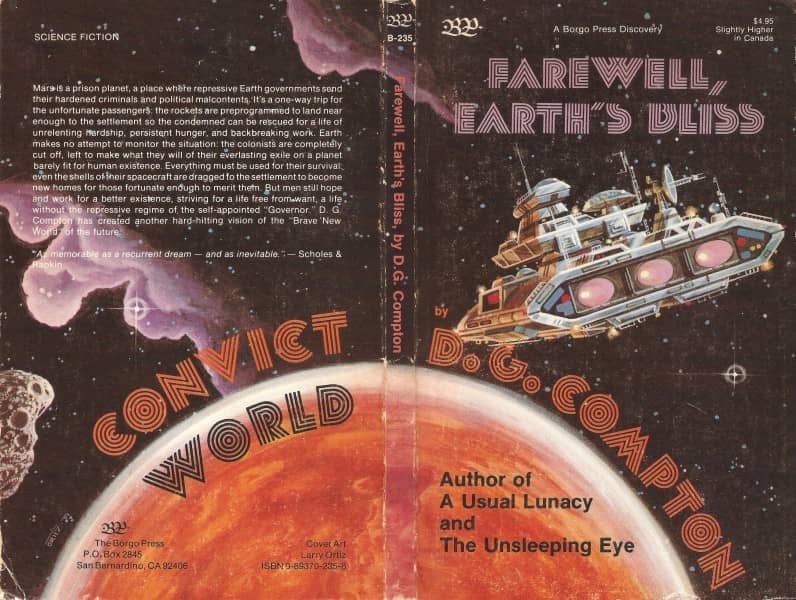

Farewell, Earth’s Bliss (Borgo Press, 1979, cover by Larry Ortiz)

You mean a science fiction novel?

No, novel, period. I haven’t read any science fiction. I really haven’t. Four or five books in thirty years. It’s not a genre that I have ever, I suppose, found all that — I should be saying this — comfortable.

It’s all right. You can be contrarian.

[Laughs.] I can be contrarian. No, I do not read science fiction. Certainly my generation of science fiction, as far as I can discern, they all came out of reading the field and graduating there. Of course growing up in England during the Second World War, there weren’t any SF magazines going on there. I do remember that we had an a couple American soldiers billeted on us, a couple of the nicest guys. And my only experience with science fiction up until adulthood was, I think, a single episode of The Incredible Expanding Man, in one of their comics.

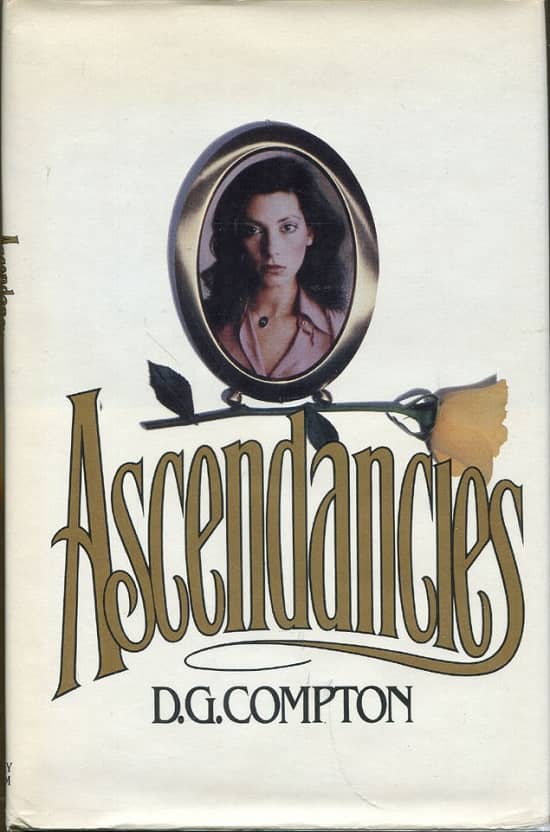

Ascendancies (1980)

I can’t place what that is.

But I remember it well. And at 11 years old I was absolutely enchanted with the idea of the incredible expanding man.

I’ve heard that they used to use American pulp magazines as ballast on ships, and then they were sold very cheaply in London, and a lot of English science fiction writers of your generation read old American magazines that they picked up for a penny or two. Didn’t you have access to this? Did you grow up in the country or in a big city?

What I’ve left out is that I come from a theatrical family. My father and mother were both in the theatre, and my initial thought was always that I would write plays. Therefore most of my literary interests as a young man were dramatic. That of course is why when I finally settled down to write, I wrote plays. I wrote radio plays because by then I had recognized the extreme difficulty in getting stage plays performed, whereas there was a wonderful, inexhaustible market at that time for radio drama.

What were your radio plays like? Were they at all fantastic or were they realistic stories?

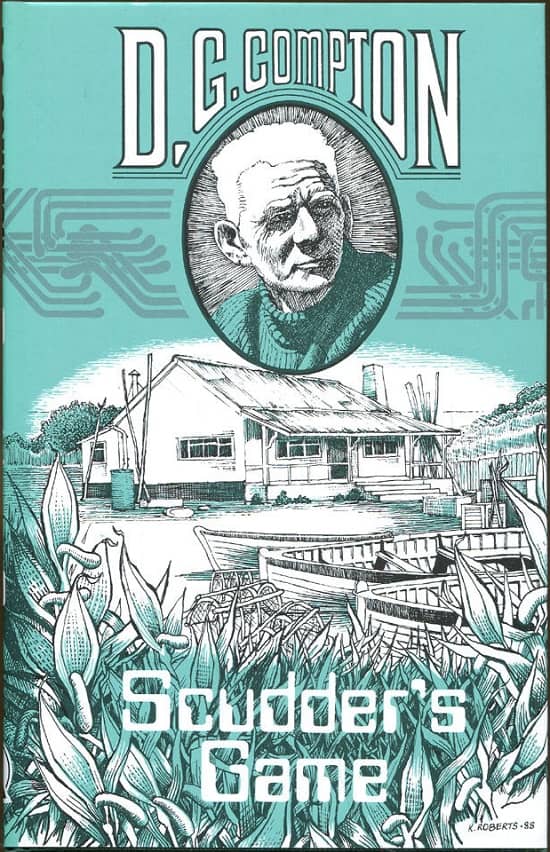

They got called avant-garde. They were very odd pieces, literary fantasies, literary games-playing I suppose. Gosh, it’s all a very long time ago now. [When the small press, Kerosina, published Compton’s Scudder’s Game, they produced a boxed Collector’s Edition that included two of his more accessible radio plays –DS] One of the more successful ones dealt with a man having to choose between a fantasy girl he was living with and a real one. Of course by the time he had hemmed and hawed and chosen the fantasy one she’d given up on him and pissed off, and so he got nothing. It was odd stuff.

But she was a real person?

Oh, no.

He created her.

He lost her by a loss of faith in her. I didn’t know what I was talking about. I was twenty-nine years old. But people did them, and particularly, as I said, the Germans at that time were very snobbish about their radio. It was kultur. Television had come along, only that was for the masses, and the Germans looked for their culture on the radio. My translator handled Beckett and Ionesco and all the people of that time who were writing very odd plays, not exactly realistic, and I fitted in to that sort of thing. I wasn’t Samuel Beckett obviously, but I fitted in with Waiting for Godot, Rhinocerous, Jarry’s Theatre of the Absurd and the Theatre of Cruelty, all the odd things that were going on at that time in Europe. All these early plays. In America too – Albee’s Zoo Story. I was in that genre.

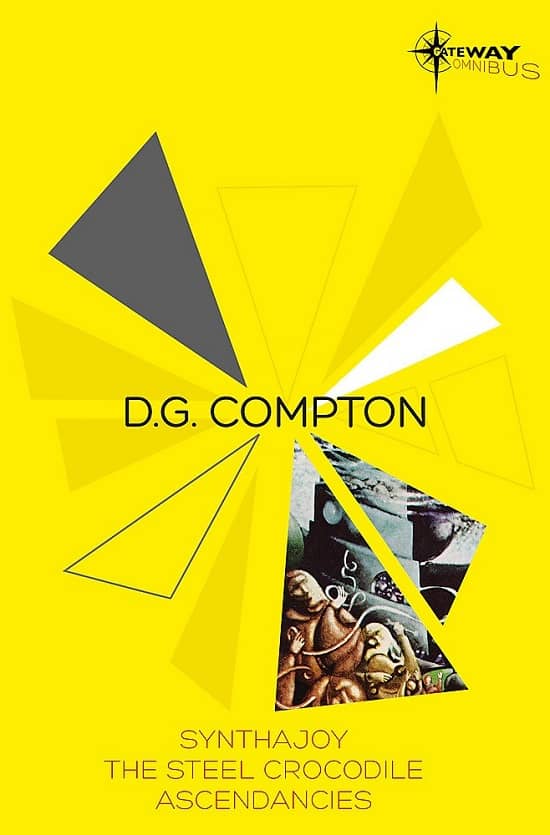

The SF Gateway D.G. Compton Omnibus (2014)

We can see in retrospect that this was a step toward science fiction, without you knowing it.

Yes, indeed. And I always had a very serious intent. I must have been a very earnest young man. I was concerned by moral imperatives, so I brought to my plays that urge toward thoughtfulness that has continued ever since, certainly. Every one of my books has a moral center, I would say.

Thank you Mr. Compton.

Our previous coverage of D.G. Compton at Black Gate includes:

The Ace Novels of D.G. Compton

Birthday Reviews: D.G. Compton’s “In Which Avu Giddy Tries to Stop Dancing” by Steven H Silver

Buy a copy of Darrell Schweitzer’s Speaking of the Fantastic III containing this interview for just $15 at his eBay store:

Darrell Schweitzer’s last article for us was John W. Campbell Jr. and the Knack for Being Wrong About Everything.

This was a great look back at D.G.Compton’s work. I read his novels avidly in the 70s, and still fondly remember them. I only wish I still had the ones I had, because I’d haul them out right now and re-read them.

I just bought the SF Gateway D.G. Compton Omnibus two weeks ago (see the pic above). It contains three of his novels:

Synthajoy

The Steel Crocodile

Ascendancies

Amazon has two vendors selling new copies for $10.49 or less:

https://www.amazon.com/gp/offer-listing/0575118105/

Great place for a new reader like me to get started!

[…] fiction as such, and has read none of his peers’ stuff, as he expressed in a fairly long 2019 interview with Darrell Schweitzer on Black […]

Wonderful read.

Thanks for this interview. I very much enjoy D.G. Compton’s novels.