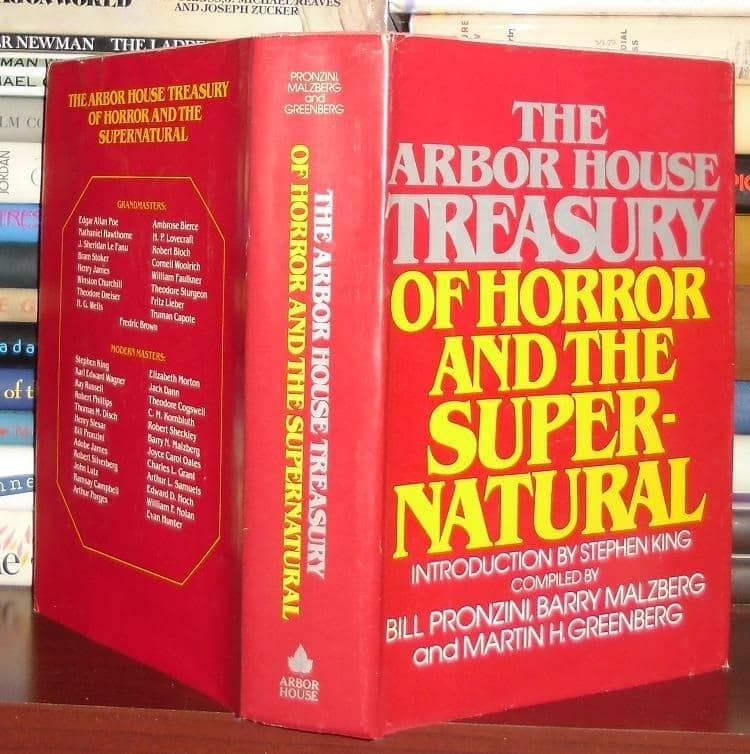

Vintage Treasures: The Arbor House Treasury of Horror and the Supernatural compiled by Bill Pronzini, Barry N. Malzberg, and Martin H. Greenberg

The Arbor House Treasury of Horror and the Supernatural (Arbor House, May 1981)

Back in February I surveyed all ten Arbor House Treasuries, calling them a “Hearty Library of Genre Fiction.” I wanted to take a closer look at a few (and I did crack open The Arbor House Treasury of Great Science Fiction Short Novels, edited by Martin H. Greenberg and Robert Silverberg), and this long Memorial Day weekend I’m settling down with The Arbor House Treasury of Horror and the Supernatural, a massive volume compiled by Bill Pronzini, Barry N. Malzberg, and Martin H. Greenberg.

This is a feast of a book, nearly 600 pages in hardcover, packed with 41 stories by Edgar Allan Poe, Bram Stoker, Winston Churchill, H. G. Wells, Ambrose Bierce, H. P. Lovecraft, Robert Bloch, Cornell Woolrich, William Faulkner, Theodore Sturgeon, Fritz Leiber, Fredric Brown, Karl Edward Wagner, Thomas M. Disch, Robert Silverberg, Ramsey Campbell, Jack Dann, C. M. Kornbluth, Robert Sheckley, Joyce Carol Oates, Stephen King, and dozens of others. It’s a the kind of thing you build a month-long book club project around.