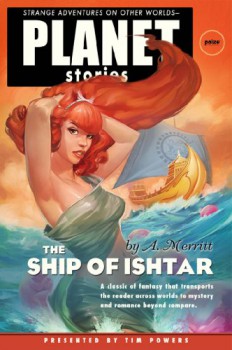

The Ship of Ishtar

The Ship of Ishtar

The Ship of Ishtar

A. Merritt (Paizo Publishing, 2009)

I first read The Ship of Ishtar in a 1960s Avon paperback I found in a used bookstore in Phoenix. This copy is so brittle that I have to specially brace the book each time I open it or else the spine will separate like the San Andreas fault and the pages flutter down in a yellow autumn fall.

What I’m saying is . . . I’m extremely glad that Paizo Publishing has brought my favorite A. Merritt novel back into print in an edition that doesn’t make me afraid of the physical act of reading it. (Go buy it here.)

It’s strange that Abraham Merritt, one the biggest sellers in the history of speculative fiction, should need an introduction at all today, but sadly he does. Merritt was a journalist by vocation, the editor of The American Weekly, but his forays into writing ornate “scientific romances” starting with The Moon Pool in 1918–19 made him one of the most popular authors of the first half of the twentieth century. Today, he’s the realm of specialists, collectors, and his work is found in volumes from university publishers and small presses. In his introduction to Merritt’s breakthrough novel, The Moon Pool, Robert Silverberg pondered this turn of events that made Merritt obscure. What happened?

Silverberg offers up his own wonderings, ultimately finding the author’s eclipse inexplicable; but I think Merritt’s unusual mixture of two-fisted stalwart heroes in epic action with grandiose, mind-bending worlds of wonder painted in prose arabesques (and millions of exclamation marks!) makes him an author who doesn’t speak to mainstream genre readers today, even if he invented the clichés of countless contemporary fantasy authors. Clark Ashton Smith started as a specialty author and has remained there. Abraham Merritt was a mainstream writer who managed to Clark Ashton Smith himself after his death, ending up as a specialty author as well. Unfortunately, such is often the way of unusual talents. At least The Ship of Ishtar is now only a few clicks away for you to purchase and enjoy.

McSweeney’s is a quirky quarterly that breaks conventional publishing boundaries with each issue devoted to a unique theme, both in terms of editorial content and physical packaging. For

McSweeney’s is a quirky quarterly that breaks conventional publishing boundaries with each issue devoted to a unique theme, both in terms of editorial content and physical packaging. For  Update: Alan Dean Foster has generously provided some comments of his own about the novelization. Please see the comments section.

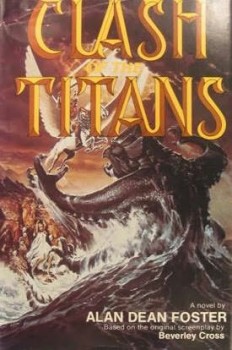

Update: Alan Dean Foster has generously provided some comments of his own about the novelization. Please see the comments section.

Pax Dakota

Pax Dakota Conan the Unconquered

Conan the Unconquered There are a lot of things to commend this book to an experienced gamer. The rules are fairly simple yet cover a lot of ground. I like how the abilities are not really tied into specific stats that are sometimes hard to justify - this system is much more fluid. It also is not conducive to rules lawyering and if there is one thing I hate, it is rules-lawyering, so this is a positive for me. I can see where the OCD crowd who wants a rule for everything could be irritated with it, but I game by the principle that story precedes rules, and this rule set is made for that mindset.

There are a lot of things to commend this book to an experienced gamer. The rules are fairly simple yet cover a lot of ground. I like how the abilities are not really tied into specific stats that are sometimes hard to justify - this system is much more fluid. It also is not conducive to rules lawyering and if there is one thing I hate, it is rules-lawyering, so this is a positive for me. I can see where the OCD crowd who wants a rule for everything could be irritated with it, but I game by the principle that story precedes rules, and this rule set is made for that mindset. Conan the Defender

Conan the Defender What’s interesting about a collection of “interfictions,” aka “interstitial fictions,” is that this isn’t just another descriptor (e.g., new wave fabulism, new weird, slipstream, paraspheres, fill-in-the-blank) made up by an editor or a marketing department or critic that subsequently becomes blogosphere fodder about how inaccurate and/or stupid it is. Rather, interfictions is the self-proclaimed terminology of an actual

What’s interesting about a collection of “interfictions,” aka “interstitial fictions,” is that this isn’t just another descriptor (e.g., new wave fabulism, new weird, slipstream, paraspheres, fill-in-the-blank) made up by an editor or a marketing department or critic that subsequently becomes blogosphere fodder about how inaccurate and/or stupid it is. Rather, interfictions is the self-proclaimed terminology of an actual  Jhegaala

Jhegaala