The Ship of Ishtar

The Ship of Ishtar

The Ship of Ishtar

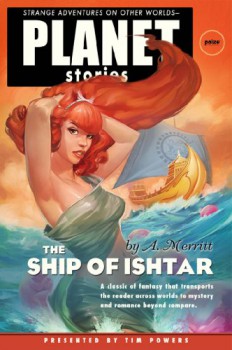

A. Merritt (Paizo Publishing, 2009)

I first read The Ship of Ishtar in a 1960s Avon paperback I found in a used bookstore in Phoenix. This copy is so brittle that I have to specially brace the book each time I open it or else the spine will separate like the San Andreas fault and the pages flutter down in a yellow autumn fall.

What I’m saying is . . . I’m extremely glad that Paizo Publishing has brought my favorite A. Merritt novel back into print in an edition that doesn’t make me afraid of the physical act of reading it. (Go buy it here.)

It’s strange that Abraham Merritt, one the biggest sellers in the history of speculative fiction, should need an introduction at all today, but sadly he does. Merritt was a journalist by vocation, the editor of The American Weekly, but his forays into writing ornate “scientific romances” starting with The Moon Pool in 1918–19 made him one of the most popular authors of the first half of the twentieth century. Today, he’s the realm of specialists, collectors, and his work is found in volumes from university publishers and small presses. In his introduction to Merritt’s breakthrough novel, The Moon Pool, Robert Silverberg pondered this turn of events that made Merritt obscure. What happened?

Silverberg offers up his own wonderings, ultimately finding the author’s eclipse inexplicable; but I think Merritt’s unusual mixture of two-fisted stalwart heroes in epic action with grandiose, mind-bending worlds of wonder painted in prose arabesques (and millions of exclamation marks!) makes him an author who doesn’t speak to mainstream genre readers today, even if he invented the clichés of countless contemporary fantasy authors. Clark Ashton Smith started as a specialty author and has remained there. Abraham Merritt was a mainstream writer who managed to Clark Ashton Smith himself after his death, ending up as a specialty author as well. Unfortunately, such is often the way of unusual talents. At least The Ship of Ishtar is now only a few clicks away for you to purchase and enjoy.

The Ship of Ishtar was initially serialized in six parts in the November–December 1924 issues of Argosy All-Story Weekly, when Merritt was reaching his height of popularity as a fiction writer. Putnam published it in hardback two years later, although in an abridged form (thirty-one chapters, down from thirty-five) and with the chapters divided into parts. This version of the text was the one printed for decades in the popular Avon paperbacks. The new Paizo edition restores the longer text, as derived from a 1949 printing.

Many of Merritt’s novels, such as The Moon Pool, The Face in the Abyss, and The Metal Monster, open with a series of chapters written in a journalistic, quasi-documentary style; sometimes these were separate novellas published before the full novel plunged into wild adventure on a phantasmagoric canvas. But The Ship of Ishtar is the purest fantasy of Merritt’s novels, and after only a brief nod to scholarship in a letter to war-rattled young John Kenton (a section cut entirely from the 1926 abridgment), the novel throws both Kenton and the reader far beyond the fields they know. Leave the modern world behind . . . you’re in the hands of A. Merritt now, and the waves are rough and sights bewitching.

John Kenton, a man whose lust for the ancient world has gotten dulled by fighting in the Great War, receives a package from the old archaeologist Forsyth: a stone from Babylon that dates to the reign of Sargon. Kenton’s investigation of the rock frees from it an amazing model of a ship, divided in the center into a bow of ivory and a stern of ebony. With the suddenness of great pulp literature, Kenton tumbles onto the ship itself as it sails the oceans of another world. Kenton finds himself in the middle of a battle between Ishtar, Goddess of Light and Life, and Nergal, God of Darkness and Death.

(Merritt does a brief bit of hand-waving with Kenton postulating about “interpenetrating worlds.” This is as far as the author moves toward the scientific-romance of his other novels.)

The leaders of the combat on the ship are the lovely Sharane, priestess of Ishtar, and the evil Klaneth, priest of Nergal. Sharane explains to Kenton that they have inherited an older conflict: a priest and priestess of the opposing gods fell in love and received the punishment of this ship and their deities trying to burn their love from them. But the couple defeated the gods’ compulsion and died together. Now Sharane and Klaneth carry on the fight, for Ishtar and Nergal remain opposed across the ship’s decks. Kenton can sway the balance of the long standoff, because unlike the other inhabitants of the vessel, he can cross the boundary in the middle.

The leaders of the combat on the ship are the lovely Sharane, priestess of Ishtar, and the evil Klaneth, priest of Nergal. Sharane explains to Kenton that they have inherited an older conflict: a priest and priestess of the opposing gods fell in love and received the punishment of this ship and their deities trying to burn their love from them. But the couple defeated the gods’ compulsion and died together. Now Sharane and Klaneth carry on the fight, for Ishtar and Nergal remain opposed across the ship’s decks. Kenton can sway the balance of the long standoff, because unlike the other inhabitants of the vessel, he can cross the boundary in the middle.

This is A. Merritt’s greatest imaginative idea—and he never had a shortage of imagination.

Temporarily enslaved on the dark half of the ship, Kenton leaves behind his fears and doubts and decides that he must conquer the great vessel—and Sharane as well. Kenton gains allies who are sworn to Nergal but wish to break free, the deformed drummer Gigi and the Persian warrior Zubran, and earns a fierce sword-mate in the Viking Sigurd, the slave chained next to him on the oars. During the adventure that follows, Kenton sometimes gets swept back to his own reality and must force himself back onto the ship . . . each time finding himself more and more distant from the real world and closer to that of Ishtar and Nergal, the world of his great love Sharane.

Merritt’s style frequently swings into archaic diction and word order that would have seemed unusual even in 1924: “Temporize with him as he had with Sharane, he knew he could not.” “And the water that dripped from him was crimsoned, crimsoned—crimsoned with his blood!” And have I mentioned how much Merritt loves exclamation marks? Even when they should be question marks! I have! Yes!

But Merritt’s Byzantine prose can also create enormous beauty for readers willing to slow down and savor it. As he violates all the common-sense modern writing “rules” about cutting down on adjective use, he also crafts prose poetry like this description of Klaneth:

As curiously Kenton took stock of the three. First the black priest—massive, elephant thewed; flesh sallow and dead as though the blood flowed through veins too deeply imbedded to reveal the creep of its slow tide; the vulture nose and merciless lips; the feral phosphoresence glimmering behind the wan pupils; the face of Nero remodeled from cold clay by numbed hands of sluggish gods within some frozen hell. Heavy; plastic with evil—but not that hot evil which often touching life is absorbed within and transformed by life’s fire. The evil in Klaneth’s face was a cold evil and one with death. And as unalterable as death.

Merritt’s meticulous attention to the details of his locations and the fictional geographies of his settings sometimes get away from him and turn baffling to any readers not following along at the slowest pace; this hinders The Moon Pool and The Metal Monster, but The Ship of Ishtar contains the greatest clarity of any of his work. The one place where Merritt goes into micro-detail is one of the book’s highlights, a piece of magical prose that takes up the entirety of Chapter Twenty-Nine. Kenton secretly follows the Priest of Bel up the tower of the city of Emakhtila and passes through each of the colored zones dedicated to different gods. (Perhaps the influences of Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death”?) As Kenton and the priest move through each deity’s temple, a great voice announces that god’s power in a long incantation:

“He goes by the altars of Ishtar, and, like the pink palms of maidens desirous, the rose wreaths of the incense steal toward him. The white doves of Ishtar beat their wings above his eyes! He hears the sound of the meeting of lips, the throbbing of hearts, the sighs of women, and the tread of white feet!

“Yet he passes!

“For Lo! Whenever did love stand before man’s desires!”

A writer today would skim through the ascension through the zones, offering maybe one invocation and then only referencing the others. Merritt describes the entire ascent, using repetition of phrases (“And he passes!”) to create a litany of an ancient time. It feels as if he reached into the mists of Sumeria and reproduced an impossibly pagan world for twentieth- and twenty-first-century eyes.

When Merritt pours on the action, the swinging blades and flying arrows generate all the excitement a sword-and-sorcery lover could want . . . which isn’t what readers might expect when they sample the author’s more lavender prose portions. The battle to seize the ship and the stand in the tower of Emahktila are passionate and thrilling action set pieces. Merritt manages to balance this swashbuckling with the vistas of the imagination in a way few authors today would even dare to attempt.

In the introduction to the new printing, Tim Powers notes that The Ship of Ishtar has an unabashedly pagan view of life that eschews contemporary moralizing, especially in the character of John Kenton, which may shock some readers: “A modern writer would not let Kenton deal with slaves and conquered crews the way he does, and would be constantly aware of Freud and political correctness.” It is a genuine surprise to see that Kenton doesn’t free the slaves aboard the ship after he takes control; he goes out of his way to raid other ship and get more slaves. And his attitude toward Sharane is frankly rapacious. But Merritt does make it clear that Kenton has lost all his connection to modernity, and with it the ideals that we take for granted. No one would dare try this today . . . all the more reason to revel in The Ship of Ishtar and it historic place in fantasy literature.

The new edition from Paizo Publishing for its Planet Stories line includes Virgil Finlay’s black and white illustrations from the 1949 Borden Memorial Edition. Finlay’s illustrations are as perfect a match to Merritt’s writing as Harry Clarke’s are to Edgar Allan Poe. The most striking of the drawings is the one for Chapter Seventeen and its remarkable scene of bubbles containing the women of Ishtar rising to the surface of the ocean to ensare the dark warriors of Nergal. This is one of Merritt’s most lyrical scenes, and a quote from it is the best way I can think of to close this review:

Out of them flowed hosts of women. Unclad, save for tresses black as midnight, silvery as the moon, golden as the wheat and poppy red, they stepped from the shimmering pyxes that had borne them upward. They lifted white arms and brown arms, arms shell pink and arms pale amber, beckoning to the rushing, sea-born men-at-arms. Their eyes gleamed like little lakes of jewels—sapphires, blue black and pale sapphires, velvet jet, sun stone yellow, witched amber; eyes gray as sword blades beneath winter moons. Round hipped and slender hipped, high breasted and virginal, they swayed upon their wave crests, beckoning, calling to Nergal’s warriors.

I loved the Merrit editions from Avon back in the 1970s with the Steve Fabian and Rodney Matthews covers.

I hate to say it, but in some ways I felt that Merritt was the perfect mixture of ERB and HPL. The Face in the Abyss, The Moon Pool and The Dwellers in the Mirage are a little bit like reading ERB filtered through HPL. And even if Merritt did get a bit carried away with his location descriptions I always love re-reading the opening chapters of The Metal Monster. He describes a Tibet that must exist somewhere even if, sadly, not in our world. It’s such a shame that he has been more or less forgotten. Maybe readers are suffering from a surplus of plenty. Back in the 70s we only had aout 60 years of Genre literature and today they have over 100 years to choose from. Even Ralph Milne Farley was still in print back then! LOL

Thank God for the Planet Stories Library

Phenomenal write-up as usual, Ryan.

Thanks for the great review, Ryan! Glad to see the critical reception this title is receiving, as actual orders have been something slightly less than spectacular.

I should point out that the Virgil Finlay plates are from BOTH the Borden Memorial Edition AND the 1940s Fantastic Novels reprint of the abridged version, which makes this the first time all 10 illustrations have ever been published together.

This was an enormously fun book to put together, and I am really proud of the final result.

A. Merritt helped, of course! 🙂

–Erik Mona

Publisher

Paizo Publishing

Planet Stories

Hey Erik,

Great to hear from you. Rich Horton talks about the Planet Stories imprint in some depth in his “Modern Reprints” column, coming in BG 14.

Sorry to hear that sales have been disappointing. Even though I already have several older editions, I’ve got it in my cart at Amazon – mostly because of that gorgeous cover! – but I admit I haven’t been in a hurry to pull the trigger on a purchase.

Perhaps that’s part of the reason for slow sales. Maybe not everyone was in as big a hurry to replace their older editions? Or am I just thinking like an old guy again? 🙂

– John

[…] While Merritt is largely ignored today (and virtually all of his novels have been out of print for decades), Paizo Press’ Planet Stories Library reprinted The Ship of Ishtar in a handsome new edition in 2009. See Ryan Harvey’s review here. […]