Neverwhens, Where Fantasy and History Collide: Tanith Lee’s Cyrion

|

|

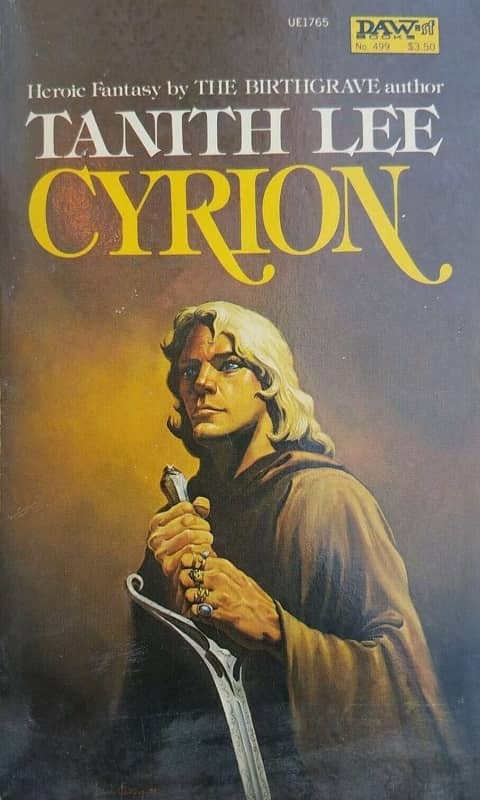

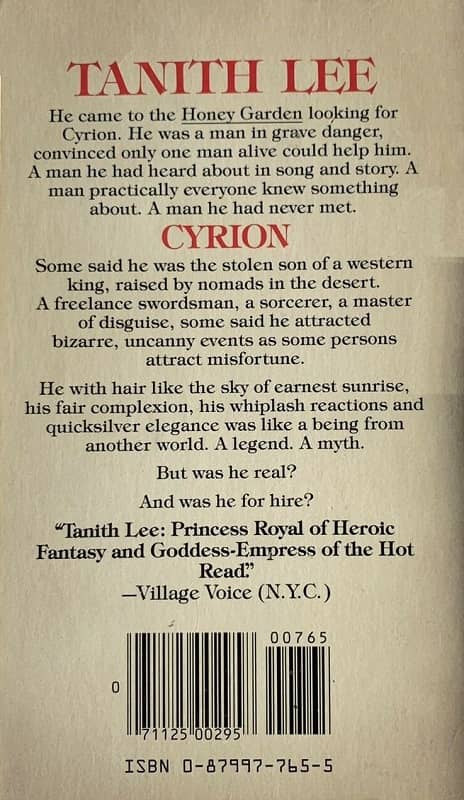

Cyrion (DAW, 1982, cover by Ken W. Kelly)

The Empress of Dreams

I hardly need to sing the praises of the late Tanith Lee (1947 – 2015). A two-time World Fantasy winner, Horror Grandmaster, Hugo nominee, yadda yadda yadda, she rose out of nowhere writing sword & sorcery (generally a male-dominated field) with the Nebula-nominated The Birthgrave, and went on to pen 70 novels, 300 short stories and create a style of lush, dark fantasy perhaps best represented by her two best-known series: The Tales of the Flat Earth and The Books of Paradys.

Lee was goth before goths, and alternative before we knew that was a thing. Her style, which was lush and baroque, but not always straightforward for the reader, prose designed to read aloud. Her settings and atmospheres were strongly in the tradition of “the Weird,” owing much to the influence of writers such as Lord Dunsany and Jack Vance.