Goth Chick News: YouTube Takes the Virtual Ruler to The Nun…

As we all know, there is no such thing as bad press. But in the world of horror, “bad” press is actually the best possible press you can get. Remember when several stores pulled the 90’s PC game Phantasmagoria off their shelves due to the violence? And suddenly if you had a copy you were the most popular kid on the block?

I do.

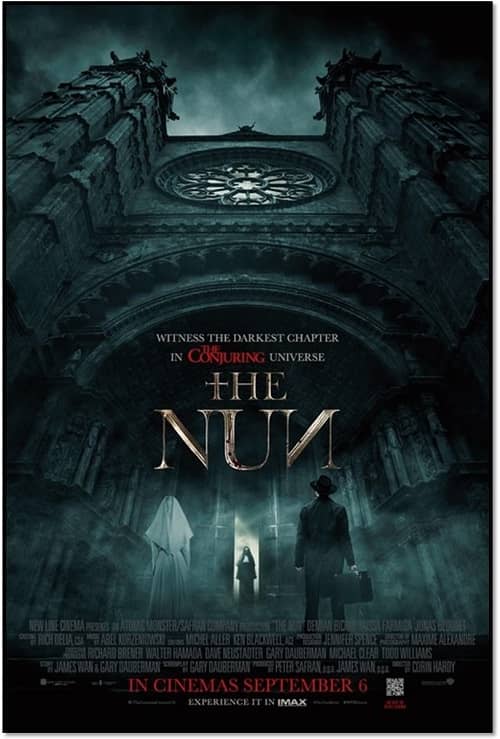

Earlier this week, a YouTube ad for Corin Hardy’s The Nun got a lot of people talking, mostly because it scared the crap out of them. In case you haven’t been following the plotline, The Nun is a spin off from The Conjuring 2, which itself is the fifth installment in The Conjuring series. Based on a story from James Wan, chief architect of the franchise, The Nun will be the chronological starting point for the entire shared universe, telling an origin story of sorts for a recurring villain, the ghoulish nun Valak.

And by the way, Valak isn’t and never has been a nun. According to the demon conjurer’s go-to guide, The Lesser Key of Solomon, a 17th century grimoire that acts a kind of Yellowpages of Hell, Valak (or Ualac, Valac, Valax, Valu, Valic, Volac) is none other than the Great President of Hell. Often depicted as riding a two-headed dragon and commanding 30 legions of demons, he takes on the visage of a small child with wings, which if you ask me, would have been way more terrifying than a nun in corpse paint. Hopefully The Nun will explain why a big cheese in the demon world has decided to take on the persona of early Marilyn Manson.

Anyway, back to the video.

The third and last screening I saw on Saturday, July 21, was a selection of short films: the 2018 Born of Woman Showcase, presenting short genre works by women filmmakers. This year saw nine movies from eight countries.

The third and last screening I saw on Saturday, July 21, was a selection of short films: the 2018 Born of Woman Showcase, presenting short genre works by women filmmakers. This year saw nine movies from eight countries. I had three screenings I planned to attend at Fantasia on Saturday, July 21. The last would be a showcase of short films, but the first two were features. The day would begin at the Hall Theatre with The Travelling Cat Chronicles, an adaptation of a Japanese novel about a cat and assorted humans. Then would come Da Hu Fa, a 3D animated film from China about a diminutive martial-arts master seeking a lost prince within a hidden valley.

I had three screenings I planned to attend at Fantasia on Saturday, July 21. The last would be a showcase of short films, but the first two were features. The day would begin at the Hall Theatre with The Travelling Cat Chronicles, an adaptation of a Japanese novel about a cat and assorted humans. Then would come Da Hu Fa, a 3D animated film from China about a diminutive martial-arts master seeking a lost prince within a hidden valley.

Strangeness has many vectors; you can be weird in multiple directions at once. Whichever shape a movie takes, it’s often a good idea to have something strange in it. Something unexpected. You can usually count on movies at Fantasia to have at least one well-developed kind of weirdness in them, but the last two movies I saw on July 19, both at the large Hall Theatre, went in very different directions; one the strangest film (in a certain way) that I’d see this year, and the other imagining a world in which there is nothing unpredictable at all. The first was an odd Hollywood-set detective story, Under the Silver Lake. The second was Laplace’s Witch, an adaptation of a Japanese science-fiction novel, directed by Takashi Miike.

Strangeness has many vectors; you can be weird in multiple directions at once. Whichever shape a movie takes, it’s often a good idea to have something strange in it. Something unexpected. You can usually count on movies at Fantasia to have at least one well-developed kind of weirdness in them, but the last two movies I saw on July 19, both at the large Hall Theatre, went in very different directions; one the strangest film (in a certain way) that I’d see this year, and the other imagining a world in which there is nothing unpredictable at all. The first was an odd Hollywood-set detective story, Under the Silver Lake. The second was Laplace’s Witch, an adaptation of a Japanese science-fiction novel, directed by Takashi Miike. The first movie I saw at Fantasia on Thursday, July 19, was at the J.A. De Sève Theatre, a Korean film called The Fortress (Namhansanseong, 남한산성). Based on a novel by Hoon Kim, Dong-hyuk Hwang wrote the screenplay and directed his own adaptation. It’s a historical war story, set in 1636 when the Chinese Qing dynasty invaded Joseon-ruled Korea. The royal court has to flee before the Qing armies, taking refuge in a mountain castle, the fortress of the title. The Qing besiege the place, and the film follows what happens in the fortress as a result. More precisely, it follows the dispute between two of the officials of King Injo (Hae-il Park): on the one hand Myeong-gil Choi (Byung-hun Lee, who was in RED 2 and was Storm Shadow in the G.I. Joe movies), the Interior Minister who wants to negotiate with the Qing and if necessary surrender; and on the other, Sang-heon Kim (Yoon-seok Kim), the Minister of Rites who wants to hold out until the end, believing that an army’s gathering in the south that will strike north and relieve the fortress.

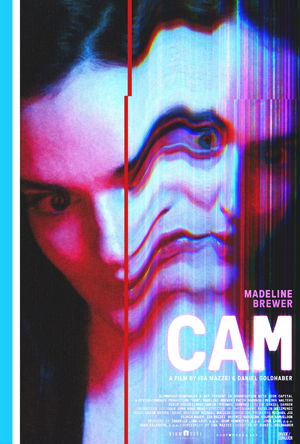

The first movie I saw at Fantasia on Thursday, July 19, was at the J.A. De Sève Theatre, a Korean film called The Fortress (Namhansanseong, 남한산성). Based on a novel by Hoon Kim, Dong-hyuk Hwang wrote the screenplay and directed his own adaptation. It’s a historical war story, set in 1636 when the Chinese Qing dynasty invaded Joseon-ruled Korea. The royal court has to flee before the Qing armies, taking refuge in a mountain castle, the fortress of the title. The Qing besiege the place, and the film follows what happens in the fortress as a result. More precisely, it follows the dispute between two of the officials of King Injo (Hae-il Park): on the one hand Myeong-gil Choi (Byung-hun Lee, who was in RED 2 and was Storm Shadow in the G.I. Joe movies), the Interior Minister who wants to negotiate with the Qing and if necessary surrender; and on the other, Sang-heon Kim (Yoon-seok Kim), the Minister of Rites who wants to hold out until the end, believing that an army’s gathering in the south that will strike north and relieve the fortress.  The only film I planned to see on Wednesday, July 18 was called Cam. Directed by Daniel Goldhaber from a script written by Isa Mazzei, it tells the story of a woman named Alice (Madeline Brewer, of The Handmaid’s Tale and Orange is the New Black) who works as an erotic webcam performer under the name of Lola — until she finds her account stolen by parties unknown. As Alice investigates she finds it’s more than just her financial information or identity that’s been stolen; someone who looks and sounds exactly like her is performing as Lola in her place, and this Lola is breaking all the rules Alice established for herself as a performer. Alice investigates and tries to regain control of her life, driving the story toward a brutal conclusion.

The only film I planned to see on Wednesday, July 18 was called Cam. Directed by Daniel Goldhaber from a script written by Isa Mazzei, it tells the story of a woman named Alice (Madeline Brewer, of The Handmaid’s Tale and Orange is the New Black) who works as an erotic webcam performer under the name of Lola — until she finds her account stolen by parties unknown. As Alice investigates she finds it’s more than just her financial information or identity that’s been stolen; someone who looks and sounds exactly like her is performing as Lola in her place, and this Lola is breaking all the rules Alice established for herself as a performer. Alice investigates and tries to regain control of her life, driving the story toward a brutal conclusion.

I had one film on my schedule for Tuesday, July 17. It was a Japanese movie called Room Laundering, which looked like an odd fusion of comedy and horror. I wasn’t too sure what to make of it from the program description, but sometimes it’s the films that don’t lend themselves to easy description that’re the most rewarding. And so here.

I had one film on my schedule for Tuesday, July 17. It was a Japanese movie called Room Laundering, which looked like an odd fusion of comedy and horror. I wasn’t too sure what to make of it from the program description, but sometimes it’s the films that don’t lend themselves to easy description that’re the most rewarding. And so here.