Phileas Fogg Finds Immortality

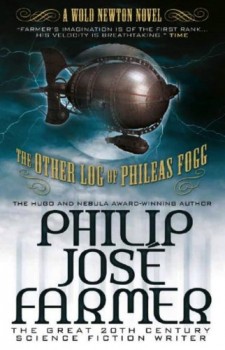

When Jules Verne created gentleman adventurer Phileas Fogg in his 1873 novel, Around the World in Eighty Days, he had no way of imagining the bizarre turn his character’s chronicles would take a century later. When Philip Jose Farmer added The Other Log of Phileas Fogg to his Wold Newton Family series in 1973, he had no way of imagining that four decades later there would exist a Wold Newton specialty publisher to continue the esoteric literary exploits of some of the last two centuries’ most fantastic characters.

When Jules Verne created gentleman adventurer Phileas Fogg in his 1873 novel, Around the World in Eighty Days, he had no way of imagining the bizarre turn his character’s chronicles would take a century later. When Philip Jose Farmer added The Other Log of Phileas Fogg to his Wold Newton Family series in 1973, he had no way of imagining that four decades later there would exist a Wold Newton specialty publisher to continue the esoteric literary exploits of some of the last two centuries’ most fantastic characters.

Farmer’s concept, in a nutshell, is that Verne’s globetrotting adventure is part of a far larger extraterrestrial conflict between two powerful alien races, the Eridani and the Capellas. Phileas Fogg was raised by the Eridani it turns out and, in the course of Farmer’s work, we learn that Verne’s Captain Nemo (the anti-hero of his 1870 classic, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea and its 1874 sequel, The Mysterious Island) is not only a Capellan agent, but is also the same man known as Professor Moriarty in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes mysteries.

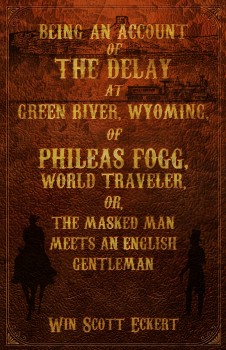

Josh Reynolds was the first author to follow in Farmer’s footsteps in a substantial fashion when he authored two direct sequels to The Other Log of Phileas Fogg for Meteor House: 2014’s Phileas Fogg and the War of Shadows and 2016’s Phileas Fogg and the Heart of Osra. Both books are set in 1889 and see Phileas Fogg coming out of retirement as the extraterrestrial conflict between the Eridani and the Capellas reaches Earth once more. The second of these titles involves Ruritania, the fictitious country from Anthony Hope’s Ruritanian Romances trilogy that began with the famous 1894 novel, The Prisoner of Zenda.

On my last trip to

On my last trip to