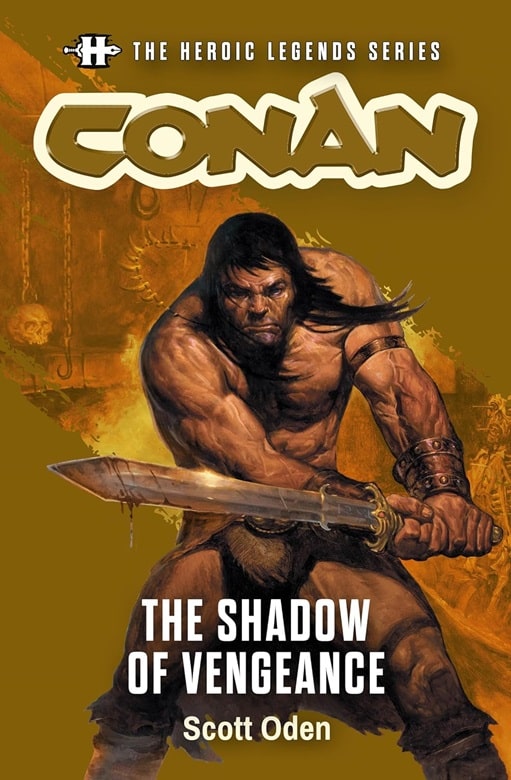

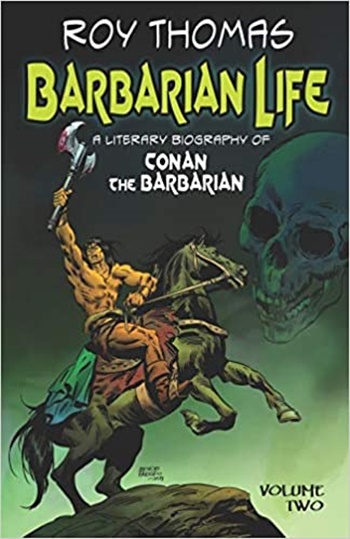

Hither Came Scott Oden: The Shadow of Vengeance, a Sequel Robert E. Howard SHOULD have Written

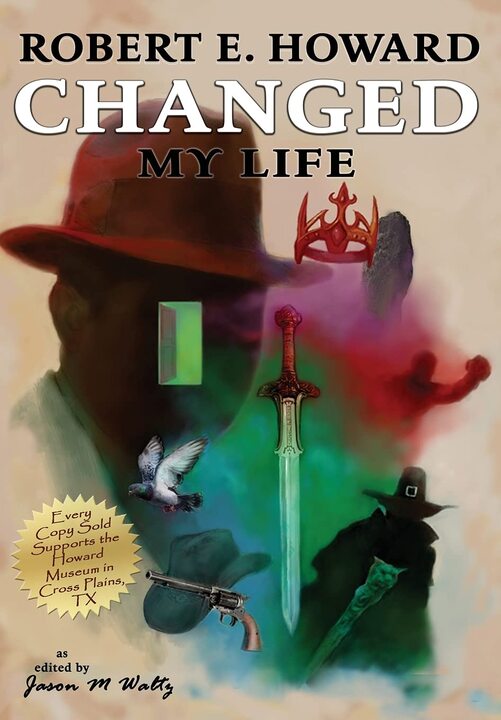

Conan: The Shadow of Vengeance (Titan Books, January 30, 2024)

Octavia tore her gaze from the grisly noose. Hope fluttered in her breast, for through the guttering smoke from scores of torches she saw the Cimmerian astride his mighty stallion. He stood motionless, a statue hewn from whalebone and gristle — save for his eyes. Even with the breadth of the Red Brotherhood between them, Octavia recognized the death fires kindled in those cold blue orbs.

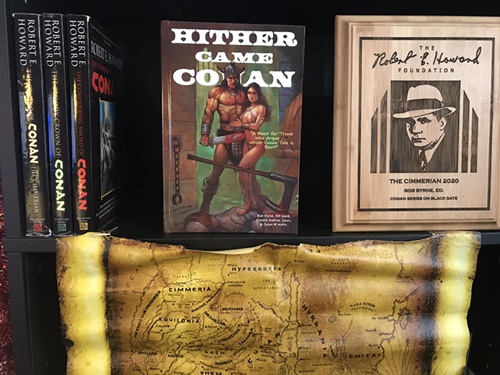

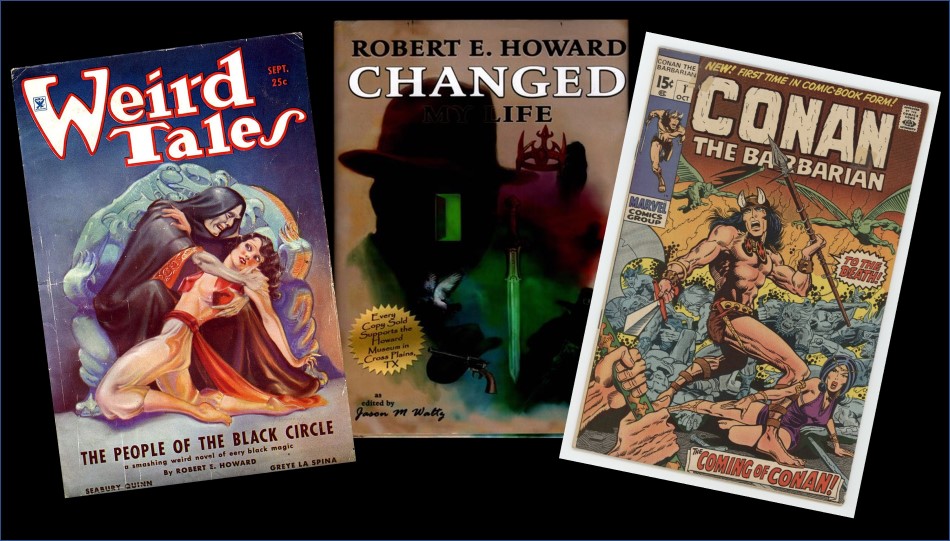

There is a magic to some writer’s prose; it pulses and pounds, like Robert E. Howard writing about Conan, or has a clever, articulate subliminity in which a bright man finds himself feeling the fool in a genius’s shadow (Doyle’s Watson writing about Holmes), that infuses a character and their canon.

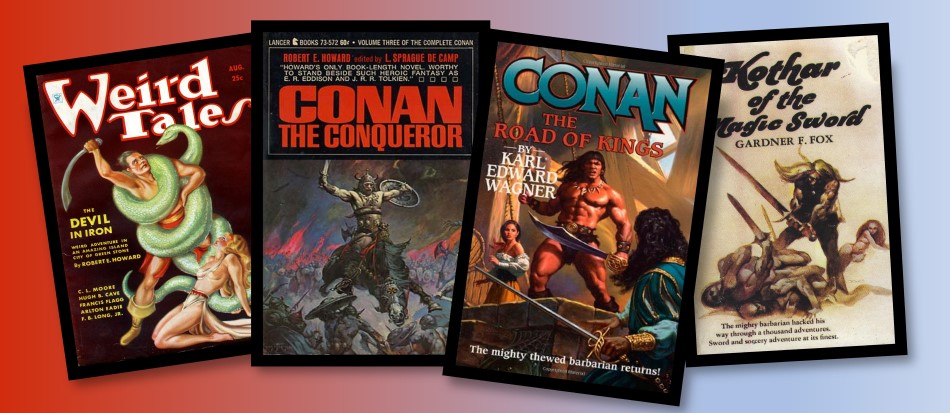

This is part of what makes pastiche such a tricky business to evaluate and review. Some hate the idea of pastiche, in which case, any review is pointless. On the other hand, pastiche — the continuation of an author’s characters in new adventures is a long-established tradition that reaches back to the tales of the pre-Classical world and continues on the reams of unlicensed fan-fic. So, let’s leave that debate for elsewhere, and just assume that you are this far because you love Robert E. Howard, you love Conan, and you want that pulse-pounding, blood-and-thunder sense of adventure you experienced long ago.