Sublime, Cruel Beauty: An Interview with Jason Ray Carney

Art & Beauty in Weird/Fantasy Fiction

It is not intuitive to seek beauty in art deemed grotesque/weird, but most authors who produce horror/fantasy actually are usually (a) serious about their craft, and (b) driven by strange muses. To help reveal divine mysteries passed through artists, this interview series engages contemporary authors on the theme of “Art & Beauty in Weird/Fantasy Fiction.” Recent guests on Black Gate have included Darrell Schweitzer, Sebastian Jones, Charles Gramlich, Anna Smith Spark, & Carol Berg. See the full list of interviews at the end of this post.

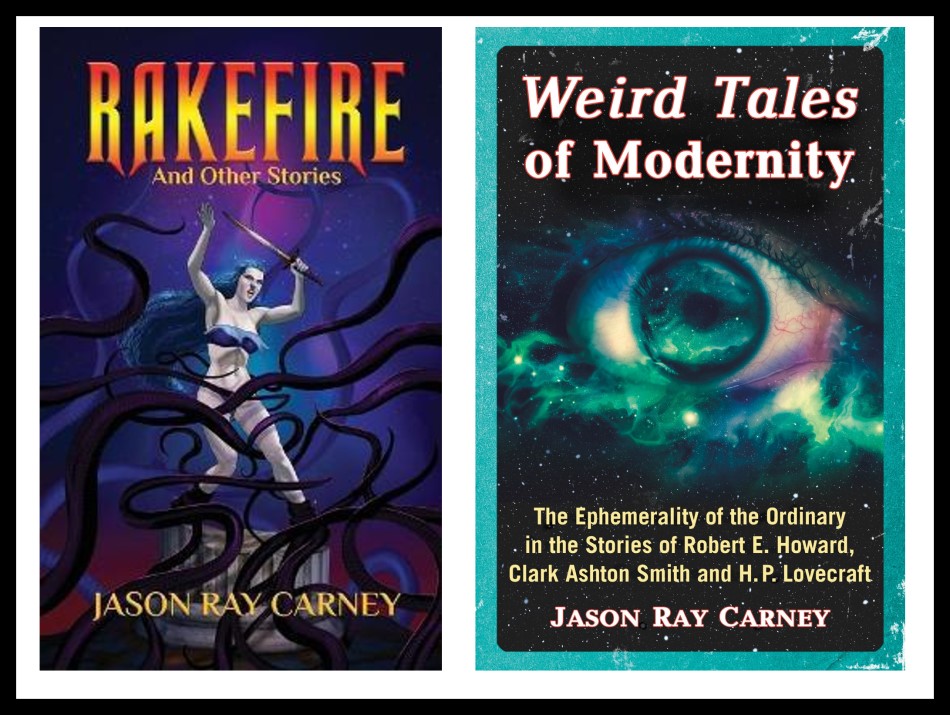

This one features Jason Ray Carney who is rapidly becoming everpresent across Weird Fiction and Sword & Sorcery communities (in fact you can probably corner him in the Whetstone S&S Tavern (hosted on Discord)). By day, he is a Lecturer in Popular Literature at Christopher Newport University. He is the author of the academic book, Weird Tales of Modernity (McFarland), and the fantasy anthology, Rakefire and Other Stories (Pulp Hero Press, reviewed on Black Gate). He recently edited Savage Scrolls: Thrilling Tales of Sword and Sorcery for Pulp Hero Press and is an editor at The Dark Man: Journal of Robert E. Howard and Pulp Studies, for Whetstone: Amateur Magazine of Sword and Sorcery and for Witch House Magazine: Amateur Magazine of Cosmic Horror. Incidentally, Jason Ray Carney has also contributed here at Black Gate with a post on Robert E. Howard’s Bran Mak Morn character and musings on How Sword & Sorcery Brings Us Life.

Well, as I interview you for (from?) Black Gate, I feel it obligatory to corner you about your feeling about ‘Black Gates,’ in particular the one mentioned in “Trigon,” a new story released in Rakefire. You seem to cast a dark light on my place of employment, even set watchers upon it. The collection indicates that black fluids are evil (whether it’s ichor or cosmic ooze). Explain:

The thrall-messenger breathlessly pleaded his case, told the council his terrible tale: high in hubris, the Sorcerer Peroptoma of Dis-Penethor, Duke of Chius, seeking secrets in the stars, had opened a Black Gate, one he could not close, and now shadows poured through it, like black blood from a wound, ravening with hunger for human flesh…. Perhaps we of Gate Watch have no right to the hope we enjoy. And yet—as I gaze upon the glimmering triangle of Cajuls wrought of my impotent war trophy, a promise of Gate Watch’s future, I cannot help but recall the words of the poet: “Destruction intensifies the process that is beauty.

Colors can be pregnant with meaning. Toni Morrison, for example, wrote a whole book about whiteness and literary history: Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (1992).

To your question: blackness, I think, is often associated with the night. In prehistoric and premodern times, the blackness of night probably indicated that one was away from fire, the safety of hearth and tribe. So, is it fair to say that black evokes feelings of anonymity, vulnerability, and sublimity? I think so. Gates and thresholds are also pregnant with meaning. Consider the literary symbolism of the threshold, the “holiest of holies.” It is a dangerous interzone. If you cross the threshold without permission, woe to you! So, Black (beat) Gate (beat), is a profoundly rich concept! It engages us deeply. Among other things, it suggests a threshold into anonymity and darkness.

With “Trigon,” I wasn’t (consciously) thinking of this wonderful website. But, truth be told, I have been reading Black Gate for years. Did I unconsciously cite this site? Maybe I did. The idea of a threshold that has to be guarded, a dangerous point of exchange that opens to another world of horror is so fascinating. Also fascinating is the trope of vigilant soldiers set to guard it.

Regarding the ubiquity of black fluids: (nerd allusion alert): have you seen Fifth Element (1997)? There is a disturbing scene where the warmonger, Zorg, is having a conversation with a cosmic entity, and the entity somehow extracts a black ooze from Zorg’s “third eye”? Who can forget that scene? In 1997, I was a Freshman in high school. All of my D&D campaigns from that point forward featured black ooze as a kind of physical essence of evil. It shows up in my fiction too.

Can you explain this comment from the “Trigon” narrator: “Destruction intensifies the process that is beauty”?

“Destruction intensifies the process that is beauty” is a paraphrase of a line from a Clark Ashton Smith poem. I will not tip my hand. It might be fun for others to track down! But I find the concept so true. One of the disturbing realizations I had as a young child was that when someone is dying you see them in a vivid way that ordinary, normal life does not allow.

As a young child, someone very close to me developed a cancer. This otherwise vital and energetic person started to lose their hair, lose weight, linger in bed; they stopped joking, they stopped laughing, they stopped moving even. As the cancer was destroying them, they were all I could think about. I remember seeing this person in their hospital bed with their eyes closed hooked up to all of the machines, and thinking to myself how much I loved them, that in their suffering this was the first time I had really seen who they were. Who they really were.

A sad feature of our life is that we become habituated to beauty. We get used to it. It becomes invisible. But when beauty is slowly destroyed, incrementally, we see it again. It’s a cruel thing.

Being Deprived of Beauty Feels Cruel

Sticking with Rakefire, the cover depicts the witch from the first story named Mera the Cruelly Beautiful (representing the story “The Ink of the Slime Lord”). So we have a trend: beauty is cruel and destructive. Heck, in your tome Weird Tales of Modernity, Chapter Eight is literally titled “Cthulhu is beautiful.” Please clarify what Beauty is?

Edmund Burke wrote an essay titled, “A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful” (1757), and he contrasts beauty with the sublime. The sublime, for Burke, is something that is in excess of any merely human categories we mentally project onto the world to organize it, to understand it, to know it, and to manipulate it. So, for Burke, hurricanes, volcanoes, earthquakes, and the vastness of the starry night sky are sublime, because they resist intellectual domestication and reject our human forms (and literally so in the case of natural disasters that destroy cities). Sublime things make us feel small, threatened, and anonymous. To use a wonderful Lovecraftian phrase, the sublime makes us feel “lost in time and space.”

The beautiful, for Burke, does the opposite. The beautiful, by way of contract, affirms us and celebrates our humanity and importance. Beautiful things remind us that we are always at home in the human world and accepted. Beautiful things are like a spouse with open arms, a mother tucking in her child at night, a cozy cabin with a smoking chimney next to a stream in the woods. For Burke, the beautiful renders the world as a human creche.

To summarize: the sublime makes us feel small and anonymous; the beautiful makes us feel important, like a swaddled child or beloved spouse. So, what is cruel beauty? That’s a hard one. Cruel beauty is a beauty that keeps you at arm’s length. Mera allegorizes that to me. Cthulhu does too. Mera affirms us. I imagine Mera as knee-shakingly attractive, but she is so beautiful that she makes those who view her feel ugly, unwanted, and unworthy.

I argue that Cthulhu is beautiful in my academic book because Cthulhu confirms a conspiracy, a scientific investigation if you will: clues, data, information, and reports are collated, and the narrator of the story, Thurston (who never actually sees Cthulhu), domesticates the enigma. Cthulhu isn’t sublime, to the extent that our intelligence cannot grasp him (it); Cthulhu is beautiful. Thurston solves the mystery. “The Call of Cthulhu” is a glorious affirmation of the power of the human intellect to pierce the deepest mysteries of the cosmos! Cthulhu is beautiful!

Do you consider any of your art beautiful? Does it scare you?

This is a hard one for me. If I hew to Burke’s vision of beauty, then I do not think I am trying to write beautiful stories. Instead, I am trying to write sublime ones. Modernity, to use Max Weber’s phrase, has “disenchanted” the world. So, a lot of what we lack in our modern lives is enchantment, mystery, a sense of the sublime. So, I think one of the main utilities of art today is to make the world strange again, to restore some of the mystery, to remind us that we are self-aware ephemeral formations of matter held in strange stasis and lost in a void. I try to do that.

Does my work scare me? I am little ashamed of it sometimes. I realize it is awkward. It is highly theorized. It is pretentious and deliberately artful, while at the same time is participates in a pulp tradition, which is supposed to be unpretentious, just for fun, and entertaining. I know it’s weird. I write mostly as a labor of love. I am lucky to not have to rely on writing as an income stream, so I can write whatever the hell I want. Many people have told me that “One Less Hand for the Shaping of Things” made them cry. So, I’m inclined to say that story might be beautiful.

What is this concept of Modernity, and why did it haunt/inspire you to write a thesis on it?

Modernity is one of those concepts with a rich intellectual history, and people spill a lot of ink over it, but it is not very complicated (in my opinion): sometimes around the 1780s, the world changed. Feudalism gave way to democracy. New technologies upset how human economies and cities were organized. Religious belief waned and changed. We stopped believing (for the most part) in the supernatural. Let me cite Max Weber again: with modernity, the world became “disenchanted.” This, of course, is only part of the story. Though this story is myopic in its Eurocentrism, it is not less valid for its narrow purview. The story of modernization outside of Europe can be told, but it will be different, with maze-like branching conversations that posit multiple “modernities.” Anyway, modernity really intrigues me.

Humans have not always lived this way, seen the world this way. For the majority of our species’ history, we have been “premodern.” One of the key features of the individual experience of modernity is a shift in the way we experience time. Arguably, the premodern experience can be distinguished by an understanding of time as cyclical. In the premodern world, things do not change forever. Instead, they cycle from one state to another state and back to the original state.

With modernity, after the French Revolution, the Industrial Revolution, the Digital Revolution, and so forth, it feels like there is no going back. We humans are thrust into a new frontier forever. Shorn of superfluities, I find being modern tragic and fascinating. We are all coping with this being modern. It is very psychologically and spiritually difficult to be modern, to be uncertain about the future.

We are mammals. We have evolved to worry and to struggle to inoculate ourselves from change. Change is threatening. I think a lot of art — science fiction, fantasy, and supernatural horror — responds to this new modern consciousness of never-ending change and absolute uncertainty.

Summoning the Unseen & Modernity

I was reading a collection of Clark Ashton Smith and came across his “The Hunters From Beyond” where he explicitly calls out Baudelaire (the weird poet who coined the term “Modernity”). The story rivals HPL’s “Pickman’s Model” for focusing on accessing and documenting the unseeable, but I was floored that weird writers appear fascinated with “modernity”. Can you summon the unseen? Why do you think he called out Baudelaire? Are you inspired to do the same?

I wanted to do in sculpture what Poe and Lovecraft and Baudelaire did for literature, what Rops and Goya did in pictorial art. That was what led me into the occult, when I realized my limitations. I knew that I had to see the dwellers of the invisible worlds before I could depict them…I longed for this power of vision and representation more than anything else. And then, all at once, I found that I had the power of summoning the unseen…” — Philip Hastane (character) CAS 1932 “Hunters from Beyond

That’s a great find! Baudelaire wrote an essay, “The Painter of Modern Life” (1863), where he defends what was a trend in the modern art of his day for painters to eschew the classical themes of premodernity for a focus on modern things like cafes, busy Parisian streets, the newest sartorial fashions, etc. . Baudelaire has a famous quote from this essay:

Modernity is the transient, the fleeting, the contingent; it is one half of art, the other being the eternal and the immovable.

Academic artists of his time liked to paint motifs from Ancient Greece, Rome, and mythology; other artists were painting other fleeting and contingent things. Baudelaire asserted that eternity and novelty are worthy of artistic treatment. Clark Ashton Smith is interesting to bring into this conversation. When Clark Ashton Smith started writing poetry, the major trend was “Modernism.”

Let me generalize a bit: when CAS was a young poet, fashionable poetry — championed by poets like Harriett Monroe, Ezra Pound, and T.S. Eliot — repudiated classical forms. It was called “Modernist” in the sense that it championed the modern, was an advocate or partisan for the modern.

CAS (and HPL) lamented this myopic focus on the modern. Could it be that to them the classical, the mythical, the recurring was figured as a kind of unseen or “occult”? Perhaps. Anyway, in the postwar period, there was a new buzzword, “postmodern,” and this refers to a kind of art that is less concerned with the old “classical/modern” debate and more concerned with the autonomy of the artistic enterprise, the way art is not a reflection of the world but how art has the potential to transform the world.

In other words, postmodern art is less about capturing the essence of the classical/eternal and/or the essence of the modern (i.e. reflecting the world as is), but is instead interested in transforming the world. Architecture is an essential art form for postmodernists because, unlike a painting or a poem, an edifice can literally create a kind of world we can lose ourselves in.

Think, for example, of those postmodern “cathedrals” in Vegas. I am imagining the spectacle of the Luxor or the Excalibur Casino. Or, what about something like Disney Land? These are postmodern because they are less about reflecting the world and more about creating a new world. That is what I am trying to do with my work. Postmodern literature is a thing.

Any suggestions on how writers can make weird/alien/unseeable stories accessible to readers? By definition, it seems a paradox.

Let me answer this briefly and follow with an elaboration: strange language.

Now for elaboration: I am a big fan of strange language: older, technical, esoteric, and liturgical language. George Orwell wrote an essay about the plain style titled, “Politics and the English Language.” In that essay, he argues against complexity in language. I love Orwell but I disagree with that argument. I think a demand for a “plain style” is a demand for a mind to be juvenile and unimaginative.

The range, mutability, and elasticity of our thoughts are directly related to the diversity of words at our disposal. We think with language. With more language at hand, we think in deeper, more complex ways.

One of my favorite prose stylists is a literary critic-slash-mystic named Walter Benjamin (1892-1940). Benjamin’s writing has an almost ritual magic dimension to it. To read certain passages of Benjamin is to jettison basic foundations of genre. We wonder what we are reading. Is this philosophy? Mysticism? Poetry? Reading Benjamin is to have a spell cast over you. Consider this brief passage from an essay he wrote about the philosophy of history:

The only historian capable of fanning the spark of hope in the past is the one who is firmly convinced that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he is victorious.

How strange. This could be lifted straight from the Necronomicon. But, if we subvocalize the text slowly, read it at the speed of exhalation hospitably, we might find a jewel-like insight: historians need to deploy radical compassion if they are to give people hope about the future; if we gaze into the past and only see enemies and failures who deserve contempt, how are we ever going to “fan the spark of hope,” i.e. give people a vision for something new?

I recently got a great review of my academic book (Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts), but one of the criticisms was that I rely too much on academic jargon. I can only quote Shakespeare in response to that: “Out, damned spot!” The reviewer’s critique was fair. I confess that one of my weaknesses as a writer is I am not skilled at audience modulation.

My wife says I sometimes “talk over” people, or that I have conversations with myself. When I’m feeling defensive I assert that I do not feel a “dumb down” what I say. It sometimes seems that modern-day mass media assumes people are dumb. I hate it. We are all smarter than we realize. I love my strange and exotic language. I legitimately think using it, discoursing with it, is cognitively good for us. Complex language short circuits people’s habituated uptake of words. In other words, it makes them think.

Sword and sorcery writers like CAS, Fritz Leiber, and Jack Vance deploy bizarre and strange language. Gary Gygax did the same in his manuals (my vocabulary was leveled up from reading AD&D manuals). Bizarre language creates a unique aesthetic effect. Whatever world the language is rendering becomes bizarre, weird, and therefore enthralling. To circle back: I believe we can only “see” a tiny sliver of the world, and strange language widens the aperture of what is perceivable.

You address Clark Ashton Smith’s Artistic Form in Chapter #4 of Weird Tales of Modernity. Please comment on the differences between CAS weird-S&S vs. REH’s writing styles, and how cadence can be employed to affect beauty or horror?

My own conscious ideal has been to delude the reader into accepting an impossibility, or series of impossibilities, by means of a sort of verbal black magic, in the achievement of which I make use of prose-rhythm, metaphor, simile, tone-color, counter-point, and other stylistic resources, like a sort of incantation. – CAS 1930 (letter to HPL)

Howard’s sword and sorcery writing, to generalize, is more visceral and concrete, a kind of aestheticized violence not unlike the acoustic violence of metal music; CAS’s writing is more lyrical and evocative, dream-like and, by analogy, comparable to the trancelike tones and beats of Dungeonsynth music.

Howard does something unique in his visceral rendering of violence:

- he pulls the reader into a raw, fleshy, organic world of the profane and

- shatters the verity of that world by bringing in a supernatural menace.

It’s very much a combat-like move: Howard lures you into the real only to surprise you by a haymaker of unreality.

CAS does something different. If Howard’s prose can be allegorized as a form of artful violence, CAS’s fiction can be allegorized as a narcotic. You smoke up some CAS and wait for it to affect you.

For example, “The City of the Singing Flame” is a psychedelic trip. It’s so beautiful, so grotesque, a vivid singularity of experience. Like the hypnotized wanderers who are drawn to the city of the singing flame, we are enthralled by the protean, flamelike forms of CAS’s writing, and, enthralled, throw ourselves — for good or ill — into those worlds. I think both CAS and REH are masters of fantasy.

You have a splendid chapter in Modernity called “The Failure of Clark Ashton Smith.” Robert E. Howard and H.P. Lovecraft are arguably more popular a hundred years after their publications, but they also addressed “Modernity”. Can you shed light on how contemporary and past audiences consume weird beauty?

When I refer to the failure of Clark Ashton Smith, I am referring to a “beautiful failure.” CAS set out to be a modernist poet. He was rejected by the editors who curated modern poetry, and cast out of the garden, if you will. Later, when he was contacted by HPL, it seemed that the possibility that he would be a celebrated contemporary poet was nil, so he turned to writing pulp fantasy, horror, and science fiction as a way to make money. So, somewhat flippantly, I view the work CAS did after he made contact with Weird Tales as a manifestation of his failure as a contemporary poet.

Regarding the second part of this question: I teach popular literature, hang out with young people, know their interests, and so I speculate about weird readers with what I think is a modicum of legitimacy, but I also acknowledge 100% that my following unpopular opinion is merely a speculative claim: I think that today’s young readers of the unreal genres (sci-fi, fantasy, and supernatural horror) are too grounded in reality.

To paraphrase William Wordsworth, “The World Is Too Much with Them.” There is a big distinction that I want to clarify:

- literary works reflect the world that produces them and

- literary works illuminate the worlds that produce them.

M.H. Abrams, a literary critic of Romanticism I cherish, uses the metaphor of “the mirror and the lamp” to clarify this useful distinction. Some artworks are mirrors, like Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, in that they hold up a mirror to reality and reflect its accurately for distanced contemplation; other artworks are lamps, in that they paint their illuminating light onto the world and thereby change the way we see it.

How does this apply to audiences of weird beauty today? I think we are in a “mirror” era and we need a new “lamp” era. I dare say that the worlds rendered by writers of the unreal — science fiction, fantasy, and supernatural horror — are not the actual world. That is important. There never was a Hyborian Age. The Necronomicon cannot be checked out from the library. Even more: the unreality of unreal worlds is really their core strength.

My understanding of new audiences is that they bring a 24-hour-news-cycle mindset to their reading. It’s as if readers and writers have a tiny microphone bead in their ears whispering to them about current events as they set down to read and write about the unreal. I think we need to least significantly turn down the volume of that bead (but not turn it off).

(Disclaimer: I am not in any way saying the writers of the unreal shouldn’t treat the real in their work; I am just suggesting that a major strength — if not the strength of the unreal genres — is their ability to adopt a pose of autonomy from the real!).

Other Dark Arts

CAS was a poet, illustrator, and sculptor; many others interviewed on this topic of “Beauty in Weird Fantasy” have other artistic talents beyond writing. Do you practice other arts (necromancy counts)? If so, can we share them (i.e., images of fine or graphic art) or mp3s (of music)? If not, which artists/pieces inspire you to write?

I draw a lot, but I am not very good! I paint Warhammer miniatures. (For Sigmar! The Emperor!) One of my favorite styles of art today is high contrast black and white ink drawings. Perhaps the favorite contemporary artist is a Cleveland-based gig poster artist named Jake Kelly whose work clearly demonstrates that he is a high-level sorcerer or warlock. Check out his work. It is sublime!

Love Retrosynth music. Mitch Hunt makes gorgeous compositions. His song, “A Perfect Life,” gives me goosebumps. It is so gorgeous. I often listen to Mitch Hunt when I write. There is an animator, Morgan King, who created a short film, Exordium, in Rotoscope style. I think King is a visionary. If I could do anything as powerful as Exordium in literary form, I would count myself a success.

I cannot resist citing the sword and sorcery writers who inspire me: everyone should read David C. Smith, Charles Saunders, Howard Andrew Jones, Scott Oden, John Fultz, and Schuyler Hernstrom. They are modern masters.

Art vs. the Artist

What are your thoughts about an artist and their work — how separate are they? Is there a character you most identify with? “Given this quote from One Less Hand for the Shaping of Things,” I predict Ayolo may be one. If so, do you prefer your study over alien lands?

[Ayolo’s] thoughts wandered to his wife Shemira and Chamberlain Brocoshio, who had, with clever arguments, convinced him to organize his caravan to the south… If he had any virtue as a merchant, it was due to his shrewdness. He was no swordsman or adventurer and was fully aware of the dangers that plagued the roads through Yizdra. Instead of sublime beauty of alien lands, he’d much prefer the ordinariness of his study, reading correspondence or tabulating accounts by candlelight; or better yet, the poetry of Thees…

Yes, I am Ayolo! Guilty as charged. My wife had a health scare and it threw me into a deep philosophical and existential mood. I remember looking at her (hopefully I wasn’t experiencing some sort of micro-stroke) imagining her as a fluid form. We see other people, our loved ones, and their faces seem static, carved in stone; but, the reality of metabolism and aging reminds us that from a certain temporal perspective, we are not static forms but fluid forms. We are all melting.

When someone you love is struck with a disease or a health problem, the cosmos reminds you of that in a rude way. With Ayolo, I also wanted to try to throw a normal, weak, bookish sort of person (like myself) into a Sword and Sorcery scenario. Finally, I cherished playing a druid in a long D&D campaign who had forsaken his life as a merchant to venerate nature; Ayolo’s story was his origin story.

As far as general ideas concerning the art and the artist, I defer to T.S. Eliot and his excellent essay, “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” Eliot writes, “No poet, no artist of any art, has his complete meaning alone. His significance, his appreciation is the appreciation of his relation to the dead poets and artists. You cannot value him alone; you must set him, for contrast and comparison, among the dead.” In other words, I believe artists are in their work, but their works are also the exuda of traditions. If JRC is in Rakefire, I hope REH, CAS, HPL, Leiber, Vance, Anderson, Moorcock, Zelazny, Smith, and Saunders (and Gygax!) are in there too.

Any future works you can share? Where do your muses plan to take you?

I am working on getting Witch House (released as this post was prepared), Whetstone 3 (also releasing), The Dark Man 12.2 done, and I have several other academic projects marinating. I am also looking forward to the consummation of a long dramatic project, an opera adaptation of Elise Wiesel’s sublime The Trial of God, for which I wrote the libretto adaptation. That is being premiered in November. This will be my first time seeing something dramatic I wrote (adapted?) for the stage on such a grand scale. I want to write a sword and sorcery novel, but I am really struggling to find the time!

Interview List Regarding #Weird Beauty on Black Gate

- Darrel Schweitzer THE BEAUTY IN HORROR AND SADNESS: AN INTERVIEW WITH DARRELL SCHWEITZER 2018

- Sebastian Jones THE BEAUTY IN LIFE AND DEATH: AN INTERVIEW WITH SEBASTIAN JONES 2018

- Charles Gramlich THE BEAUTIFUL AND THE REPELLENT: AN INTERVIEW WITH CHARLES A. GRAMLICH 2019

- Anna Smith Spark DISGUST AND DESIRE: AN INTERVIEW WITH ANNA SMITH SPARK 2019

- Carol Berg ACCESSIBLE DARK FANTASY: AN INTERVIEW WITH CAROL BERG 2019

- Byron Leavitt GOD, DARKNESS, & WONDER: AN INTERVIEW WITH BYRON LEAVITT 2021

- Philip Emery THE AESTHETICS OF SWORD & SORCERY: AN INTERVIEW WITH PHILIP EMERY 2021

- C. Dean Andersson DEAN ANDERSSON TRIBUTE INTERVIEW AND TOUR GUIDE OF HEL: BLOODSONG AND FREEDOM! (2021 repost of 2014)

- interviews prior 2018 (i.e., with John R. Fultz, Janet E. Morris, Richard Lee Byers, Aliya Whitely …and many more) are on S.E. Lindberg’s website

S.E. Lindberg is a Managing Editor at Black Gate, regularly reviewing books and interviewing authors on the topic of “Beauty & Art in Weird-Fantasy Fiction.” He is also the lead moderator of the Goodreads Sword & Sorcery Group. As for crafting stories, he has contributed five entries across Perseid Press’s Heroes in Hell and Heroika series and has an entry in the forthcoming Weirdbook Annual #3: Zombies. He independently publishes novels under the banner Dyscrasia Fiction; short stories of Dyscrasia Fiction have appeared in Whetstone and Swords & Sorcery online magazines.

Dr. Carney was my professor at CNU and set my brain on fire. He talks like this.

Is this a President Trible call out? Thanks, Brick! Whoever you are, I hope you’re well! Haha

Prof. Carney may be the first person whom I have heard offer an aesthetic defense for the Gygax plethora of polearm names. Is the world more enthralling when we wield a guisarme? I do think it has a more engaging texture, perhaps a roughly edged surface that snags and grabs at us instead of sliding smoothly off like a silken stereotype.

“Is the world more enthralling when we wield a guisarme?” This is found poetry! 😉 (And, yes!)

Wow, what an amazing and enlightening interview! Some really deep thoughts about CAS and REH–brilliant insights. This discussion reminded me of how I used to feel when I’d read a Tom Ligotti interview…intrigued, inspired, and more than a little awed. (And thanks for the shout-out, Jason!)

Thanks, sir! I recently read your *Worlds Beyond Worlds.* Such a treasure trove. “Chivaine” is an S&S masterpiece, imho.

This really opened my eyes to better defining types of “weird” allures, and am fascinated with the sublime now. I love the intellectual leads to authors like Edmund Burke and Walter Benjamin. I’m glad JRC was so open to sharing his madness.

[…] (2) MODERN THOUGHT. S.E. Lindberg interviews pulp scholar and sword-and-sorcery author and editor Jason Ray Carney at Black Gate. “Sublime, Cruel Beauty: An Interview with Jason Ray Carney”. […]

Excellent interview!

Re: CAS, sometimes when I read some of his mythos fiction, I get a feeling he’s poking some fun at it all. Do you get that feeling, or is it just me?

Thanks, Adrian! I see that too. You do not need to read very many of CAS’s letters to see that writing prose fiction for *Weird Tales* was not what he really valued. He wanted to be a poet. Even still, his work is great, even if he didn’t value it as much as I do!

I’m glad Fantasy/SF/REH fandom is getting academics attracted to the genre. Academic journals like The Dark Man that are also geared to non-academics are great.